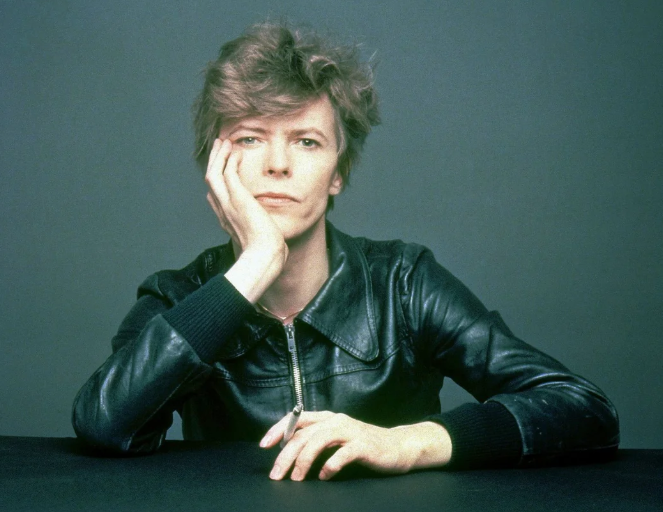

Around May/June 1977, David Bowie and Iggy Pop found themselves free of rural France and in Berlin, doing what any self-respecting culture vultures and gatekeepers of taste would do on the back of two successful (and future classic) albums (Low / The Idiot); they wandered around the city’s Brücke Museum, absorbing the Teutonic culture and getting familiar with the very fabric of Germany. Amongst the largest collection of German Expressionism on the planet, between the Kirchners and the Heckels, the Bleyls and the Schmidt-Rotluffs, they chanced upon Otto Mueller’s 1916 painting Lovers Between Garden Walls. Its loose and flowing watercolours made quite the impression on the magpie-minded Bowie and he returned time and again to soak it in, committing it to memory until a suitable use could be found for it.

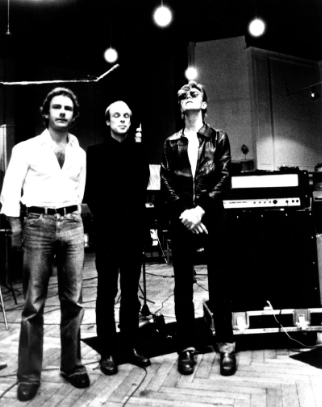

Collaborating with Bowie on the album he’d quickly release to follow Low were Brian Eno and Tony Visconti. Eno was there to add the wacky vibes, an arty farty court jester enabling and encouraging Bowie to draw on oblique strategies upon which he’d create and build his new art. ‘Once the search is in progress, something will be found’, ‘Imagine the music as a moving chain or caterpillar’, ‘Remove specifics and convert to ambiguities’. Making sense of it all at the controls was Visconti, a level head amongst the highbrow lunacy that Eno championed, and somehow, over the course of five or six weeks, the album ‘Heroes‘ took shape.

One backing track they’d built up – ‘Use exactly five chords’ – was the pick of the bunch but remained vocal-free. It was built upon a repetitive groove, played by Bowie’s Young Americans guitarist, Carlos Alomar, with added thunk from the rhythm section of George Murray (bass) and Dennis Davis (drums).

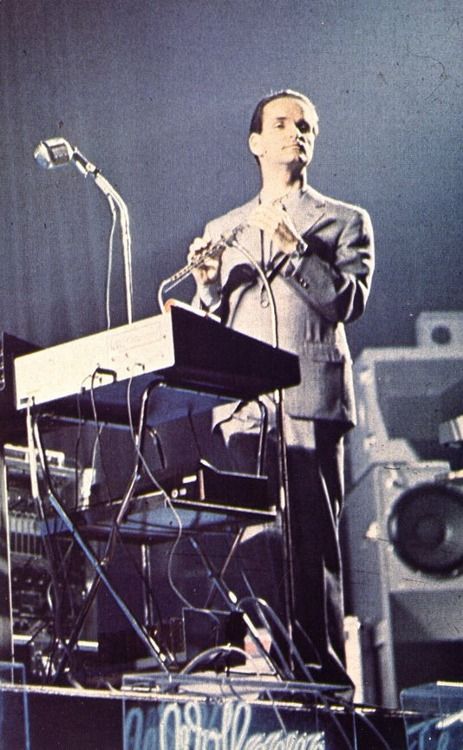

As a backing track in this state, it was perfectly serviceable, but a fantastic layer of Robert Fripp guitar spread generously across the top of it transformed it into something wild and eerie and utterly sci-fi. Fripp had found all the sweet spots in the studio where his guitar would sing and feedback and marked the spots on the studio floor with tape. As the backing track played in his headphones, Fripp prowled the studio, coaxing elongated textures of harmonic feedback while he flitted from sweet spot to sweet spot, magnetising the results on tape forever. The resultant track had to bubble and stew and ferment before being afforded a lead vocal, but when it arrived, it landed quickly.

The official Bowie story of the time is that he happened to look out of the Hansa Studio window and there, under a gun turret by the Berlin Wall, were two folk wrapped in a romantic embrace. In later years, it emerged that the man in the embrace was Tony Visconti. His marriage was crumbling and he’d found himself entangled (in every sense) with local jazz singer Antonio Maass. Bowie wanted to immortalise the embrace in song; the romantic notion of two people kissing by the Berlin Wall, defiantly against the world around them, seemed too good to ignore. As he wrote the lyrics, his mind cast itself back to the Brücke Museum and Otto Mueller’s painting of two lovers between the garden walls. Visconti and his new girlfriend were playing the picture out in front of him. Give it a word – serendipity. Give it two – beautiful happenstance.

David Bowie – Helden

It is, like all the best Bowie tracks, from Life On Mars to Absolute Beginners to Where Are We Now? a proper builder, Bowie’s voice rising with each subsequent verse, the high drama unfolding as each chorus gives way to a new part, his voice hoarse and high yet in total control as it gradually plays out. “Heroes” too has that magical groove and swing, it is downbeat yet danceable. Even when sung in German (especially when sung in German?) “Heroes” is an unstoppable force.

“Heroes” (those quotations are important, they suggest sarcasm; we could be heroes? Aye, right!) would be the album’s lead single, released towards the end of September, (that’s a mere 48 years ago, young man). It has since become one of Bowie’s statement pieces. Anthemic yet tender, it grew a life of its own. It was sung at Live Aid, its meaning doubling up as a metaphor for all who’d attended and taken part in the event. It blasted out at the opening ceremony of the 2012 Olympic Games in London. It was, in a sweet turn of events, played in Berlin by Bowie after the Wall came down, 15,000 reunited Berliners singing it back to him as he cried unstoppable tears.

It also forms part of a brilliant scene at the end of 2109’s Jojo Rabbit, where the young titular hero dances a very Bowiesque dance on his doorstep with the unattainable girl of his dreams. The film maker (Taikia Waititi) used the German-language version for added authenticity. As an aside, he also scores the start of the film with German-language Beatles hits, played out over fast-cut film of Hitler rallies; Beatlemania recast as Adolf-mania. Very clever stuff. If you’ve never seen it, rectify that at once.