A seismic occasion occurred today with the breaking up of the boy’s football goals. A present for his 7th birthday, they’re being dismantled and gotten rid of after the best part of a dozen well-worn years. Or should that be seasons? They’ve been a feature of the back garden almost as much as the cluster of plant pots on the wall (sorry, shy line) and the shrubs that have since grown into trees. I haven’t felt this resigned and melancholy since the day we gave his big sister’s dolls house away to friends with younger girls. Like Andy in Toy Story 3, this seems momentous yet inevitable; the literal breaking up of childhood, the boy now a young man with a full driving licence and miles of foreign travel on his passport and miles of Edinburgh Marathon training in his legs and a place on a desirable course at Glasgow University and a healthy indulgence of the social life that goes with it…what does he want with a set of football goals these days?

It wasn’t always like this. I remember building them on a freezing cold November Sunday. My parents had taken the kids away for the afternoon and we had a couple of hours window in which to construct them in secret. I had, at best, one and a half built, with no nets yet attached, when I heard my dad arrive with the kids. The half-built goals were quickly and roughly shoved to the wall, just under the kitchen window and not finished, under torchlight, until the boy was in bed. The desired surprise effect the next morning was immediate and thrilling. Throwing open his curtains, the boy was out in his pyjamas and dressing gown before the kettle had fully boiled, booting his ball goalwards with an enthusiasm and determination that barely let up for a decade.

He’d pester me to play. “One more game! Just one more game!” Spring. Summer. Autumn. Winter. It didn’t matter. “Your tea’s out!” That didn’t matter either. It’d be dusk, then dark, then pitch black and he would still be reeling off excitable and breathy high-pitched commentary of imaginative matches where he, the wee guy, overcame the odds to defeat me, the big guy. “It’s through the legs…he leaves him dizzy…he rounds the keeper…it must be……GOAL!!!” and he’d run away, arms aloft like a million wee kids before him and since.

His pals would be round. Half a dozen wee boys getting torn into a properly competitive game. Yellow cards, defensive walls at free kicks, the lot. If I was lucky, there’d be an odd number and I’d be called into action like some ageing and doughy super-sub to make up the numbers. We had balls lost to the railway line over the fence. Balls lost to neighbours on both sides. Burst balls. Burst nets. Broken plant pots. Broken fences. Broken wrists. Broken hearts when it was bedtime.

He was football daft. He joined a team. He trained one night a week with them, and the other six nights he’d play with me; passing drills, turning and shooting, shielding the ball, tackling. Everyone – everyone – was bigger than him (not now) and this informal training helped him to develop his game. It’s only in the last year or so that he’s stopped playing, by which time he was the best passer of the ball in the team, the designated corner taker where more often than not his crosses would be met full-on by the head of an aggressive team mate, and the most industrious and hard-working player in the squad, his envied and much talked-about close-control skills honed over hours on his wee pitch out the back door.

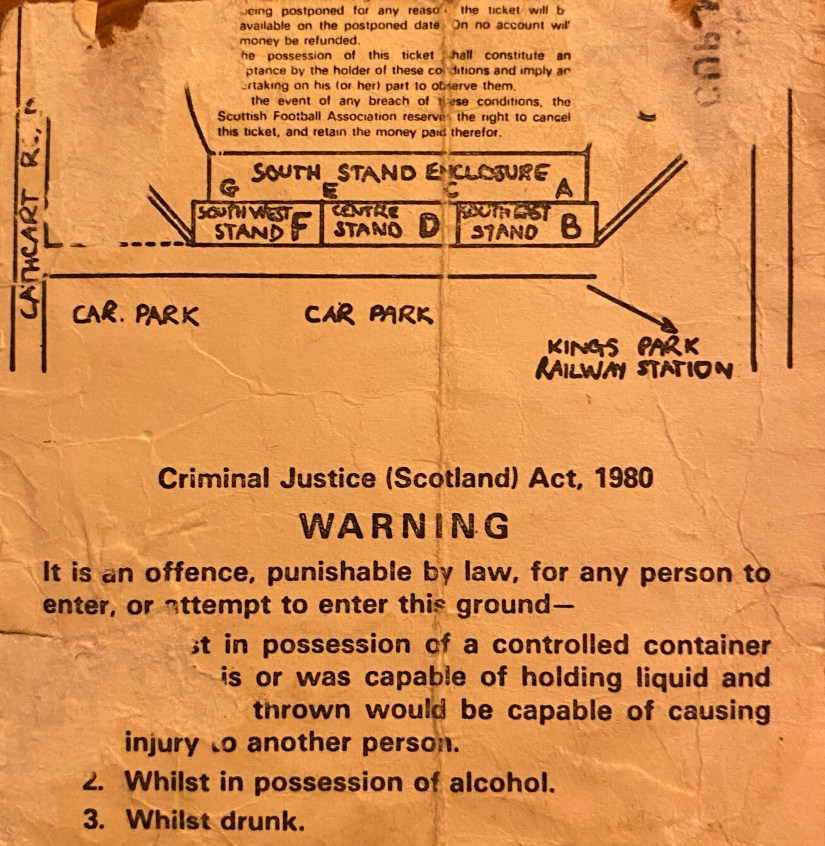

He still is football daft. We go to games together (Kilmarnock and Scotland) and I hope this never ends. I’m sure he’d like to travel with his pals to more games than he has done already, but there’s an unspoken rule that the football is our thing and our thing alone, and that’s just fine with me.

Before the breaking up of the goals, we had just one more game. The pitch (let’s not be pretentious any more, it’s a few metres of astroturf) suddenly seemed much smaller than before. The acres of space down both wings has been somewhat reduced. The ease it which both of us could turn one another inside out has greatly diminished (for one of us, at any rate). And don’t even think about scoring. Now I see what he’s seen for all those years – a big giant between the posts with nary an inch on either side to try and squeeze the ball into. No wonder he got good at the trick stuff, regularly wrong-footing me before wheeling away to celebrate with his mum at the kitchen window (sorry, the fans in the Directors’ Box).

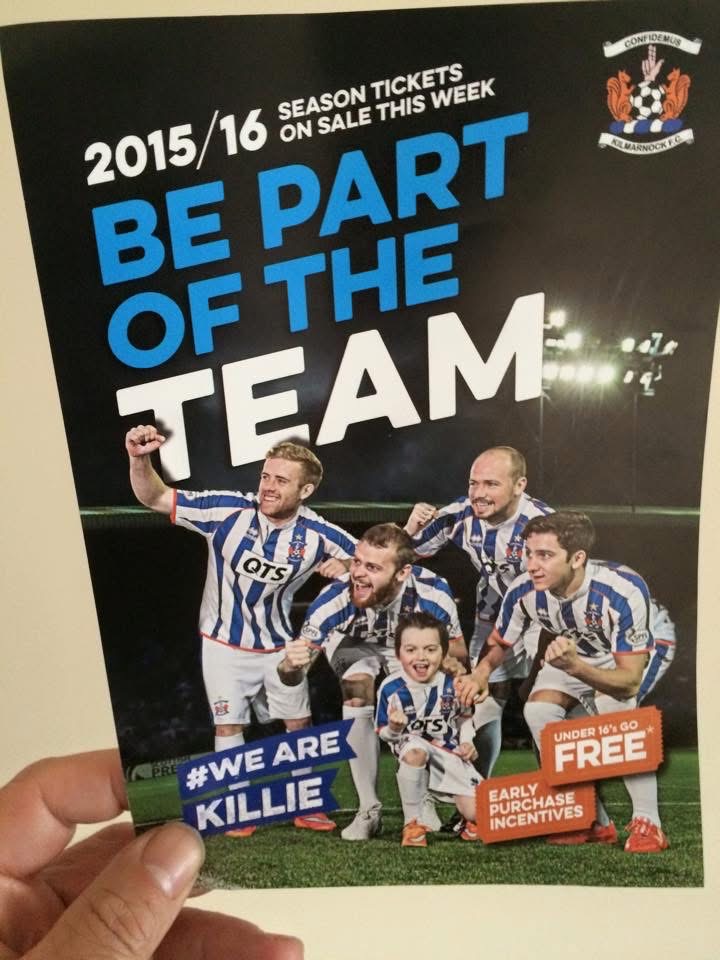

“Replicate your goal celebration,” said Killie, “and we’ll make you the poster boy for the season ticket campaign.”

“Replicate your goal celebration,” said Killie, “and we’ll make you the poster boy for the season ticket campaign.”

I’d like to tell you I let him win that final game. That’s what dads do, after all. But, in something of a role-reversal, he went easy on me. He’s bigger, stronger, more skilful. And smart-arsed with it too. So he rainbow flicked and nutmegged and stepped-over and wrong-footed me until I was dizzy. Then, as he momentarily slept at his front post, the pair of us bent double with laughter, I slotted a fly back heel in for the winner. Competitive dad to the very end.

“Penalties!” I suggested, eking out the very last of this last match. I beat him 3-2 on that front too. So, I’m the winner…but more importantly, I’m the winner. Who wouldn’t want to still be kicking a ball about with their children when they’re 18?

After full time, with extra time added on, it’s game over for the goalposts. But not the father/son thing. That’s got many more years still to go.

Here’s Roy Harper’s wistful and ultra-melancholic When An Old Cricketer Leaves The Crease. Maybe it’s Harper’s resigned voice. Maybe its the stately brass band that carries him home. Or maybe it’s the realisation that I’ll never kick a ball with the boy in the same way again. Either way, I appear to have something in my eye.

Roy Harper – When An Old Cricketer Leaves The Crease