In the future, historians of popular culture and those who gatekeep the ancient art of music blogging will point to this date – the 9th of February, in the year of our Lord two thousand and twenty-five – as the day that Plain Or Pan, that once-great leading music blog, began its slow but steady and inevitable terminal decline. The reason? Dire Straits.

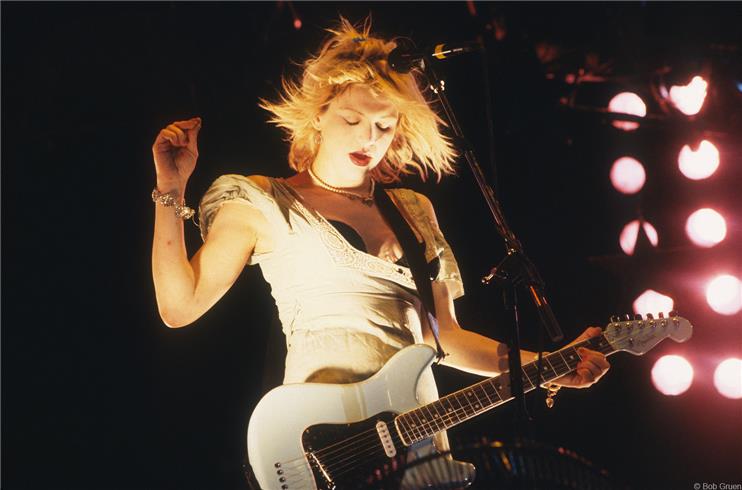

There was a great old Top Of The Pops episode on BBC4 the other night. Presented by a smug ‘n smooth Simon Bates, it featured the hits of this week from 1981; a jumpin’ and’ jivin Stray Cats, their outrageous quiffs riding the crest of the rockabilly revival wave; Blondie’s Rapture on video, a blue eye-shadowed Debbie in shorts and not much else, her mile-wide smile bordered in bright red lipstick and stirring something in me even then as an 11 year old; the much-lampooned (’round here at least) Spandau Ballet, dressed ridiculously – jackets worn over the shoulders, layers and layers and layers of fabric, billowing blouses and baggy breeks and what looks like Hunter wellies and woolly socks turned over the top of them – a proper fashion student’s juxtaposition of NOW!, transplanted straight from the Blitz club direct into your suburban and beige living room.

The highlight of the Ballet? The Spands? is, as always, The Hadley. He’s got a bit of a beard going on here, highlighting his (admittedly impressive) razor-sharp jawline. His hair though is a disaster; teased, lank and greasy it’s swept to one side like an unfortunate outgrown Adolf do, (Spandau, eh? Makes y’think), his skinny mic technique and gritty voice cementing his pure soul credentials to those lapping it up at crotch level in the studio’s front row. Behind him, the band – his band – pose and preen and pretend to play like it’s the last time they’ll ever be allowed on the telly…which really should’ve been the case. It’s quite an astonishing performance. Should you wish to see it, here y’are:

Daft one hit wonder Fred Wedlock comes and goes, thankfully, in the short time it takes to fix yourself a top up before the hard-rockin’ Rainbow show up on video; tight tops, tight red jeans, bright white guitars. A splash of satin. A dash of bubble perm. Proper music for proper people, y’know.

And then there’s Dire Straits.

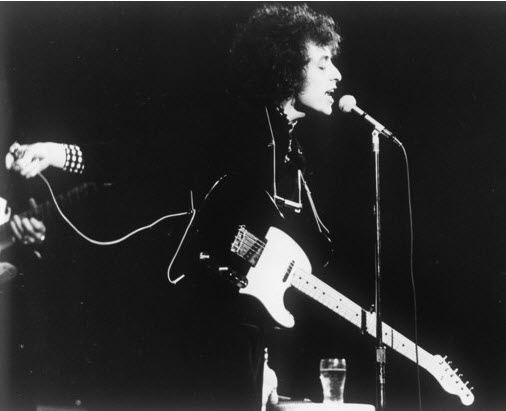

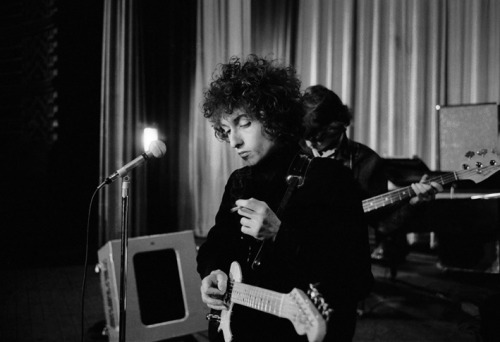

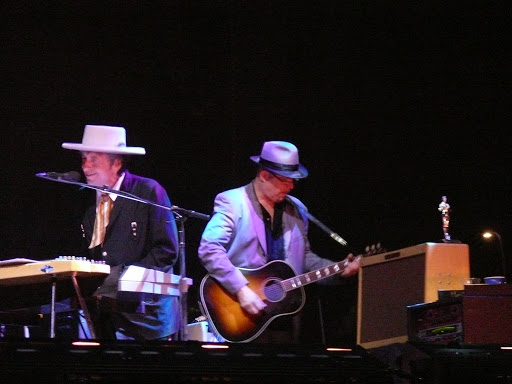

They’re a good four years from ubiquity, Dire Straits, but look! The red sweatband that would be used to hold Knopfler’s mullet in place at some point down the line is right here, right now. There it is, strapped round his right wrist as he picks the opening to Romeo And Juliet on his Brothers In Arms National steel guitar. Just as that guitar was elevated from mere Top Of The Pops studio prop to cover star on their massive hit album four years into the future, that sweatband clearly grew in direct proportion to Dire Straits’ record sales too.

They’re not a Top Of The Pops act, Dire Straits, and don’t they know it.

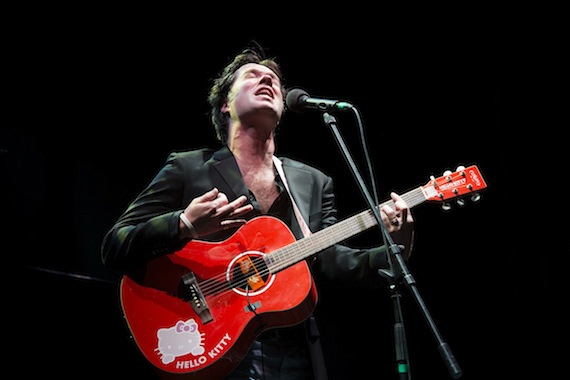

Someone has had the gumption to get them to a tailors before recording. For a bunch of four un-popstarry guys, they look surprisingly great. Knopfler is wearing a dark blue pinstripe suit jacket atop a white tee – he hasn’t yet found his penchant for vests – and he looks like a groovy English teacher doing a wee slot at an end of year school assembly; self-conscious, smiling nervously but with the chops in his fingers to validate his being there.

The group behind him is supremely stylish. Like, if someone showed you a picture of them and told you this was The Strokes, you wouldn’t be a fool to believe them. John Illsley on bass is tall, angular and moody. Chiselled of cheekbone and dark of brow, he wraps his massively long fingers around the neck of his massively long Fender Precision bass and plays it effortlessly, precisely even, pouting on all the right notes, looking into the middle distance for added appeal. He has slightly more buttons undone on his shirt than is exactly necessary, but then, the bass players are always the ladies’ men, are they not?

The guitar player – is it Mark’s brother David? – plays a hot Strat that may well have been borrowed direct from that there Rainbow. His vivid blue suit jacket sleeves are rolled up, Crockett and Tubbs-style, his large triangular collar mirroring the sharp edges of his Illsley-rivalling cheekbones. He too seems to have forgotten that shirts button all the way to the Adam’s apple.

The drummer? He’s in a capped sleeve t-shirt. Clearly, the band budget stretched to the three Straits who’d be standing directly in front of the camera. There’s a piano player stuck somewhere in the shadows too, but who’s bothered about him? Not the Top Of The Pops cameraman, that’s for sure.

Romeo And Juliet, but.

There used to be that ‘guilty pleasures’ trend a few years ago, y’know, where uber-cool folk – or, rather, folk who thought they were uber-cool, admitted to liking Rock Me Amadeus and Eye Of The Tiger and stupid stuff like that. I blame Brett Easton Ellis for his irony-free fashioning of Huey Lewis And The News in American Psycho for giving sensible folk the idea of ‘the guilty pleasure’. What nonsense! Music is music. It’s either good or bad, right? Soft rock, never fashionable amongst any demographic, is well represented in guilty pleasures circles. Anything by Stevie Nicks (Rooms On Fire! Edge Of Seventeen!) Steely Dan’s Do It Again. Kim Carnes’ Bette Davis Eyes. They’ll never fail to hit the spot. Them….and Dire Straits’ Romeo And Juliet.

It’s a fantastic record; expectant, storytelling verses, tension building pre-choruses, heart-melting choruses. It’s also a fantastically well-produced record. Dire Straits may well be a guitar band, but listen especially to the drums! Four to the floor tambourines. Unexpected snapping snares. Rocksteady rimshots. Hi-hat ripples and end-of-line paradiddles. Those patterns are exquisite! In the verses. In the bridge. In the choruses. Subtle and inventive, they elevate Romeo And Juliet from mere singer/songwriter ballad into brave new territories. Pay attention to those drums the next time Romeo And Juliet enters your orbit.

Everyone knows that the Knopf is a fantastically idiosyncratic guitar player; strictly no plectrum, a thumb and fingers style of playing, slow and lazy chord changes, snapping and twanging solos, and it’s all over Romeo And Juliet. But it’s his vocal delivery that really does it here. In the verses, he half speaks in that languid Tyneside Dylan drawl of his, but occasionally he slips into a vocal cadence that’s pure Lou Reed. Play Street Hassle or New York Telephone Conversation then play Romeo And Juliet and tell me I’m wrong. You and me babe, how about it? Pure Lou. It’s 1981, right? Kinda makes sense, like it or not.

So, yeah. Romeo And Juliet by Dire Straits. On Plain Or Pan. You can unsubscribe on the right there, any time you like.