It’s a long way from Scotland to Jamaica – about four and a half thousand miles at the last Google search – but the two small nations are inextricably linked. Thanks to mercenary tobacco merchants who set sale from Scotland’s second city a couple and more centuries ago, Glasgow has visual reminders of its links to the tobacco and slave trade slap bang in the middle of the city centre.

Road users enter and circumnavigate the city via the Kingston Bridge. The Sub Club, the world’s longest-running underground dance club, can be found on Jamaica Street. The streets that surround the city centre form an area known as the Merchants City, the street signs hung in long-standing tribute to the men who brought tobacco, wealth and dubious social values (and lung cancer) to the west of Scotland; Buchanan, Ingram and Glassford, to name but three, made fortunes trading in people and tobacco, using their dirty gains to build impressive townhouses that still stand today. One of them, William Cunninghame’s majestic Roman-columned mansion – Saturday afternoon hang-out for every subculture since the teddy boys – has operated for almost 30 years as the Gallery of Modern Art. You might recognise it as the building behind the statue of the guy on horseback with a traffic cone permanently skewed on his head. I dunno what a complex man such as the Duke of Wellington would make of Glasgow’s involvement in slavery, but there he stands, a traffic-coned and shat on guardian of one of the city’s finest architectural triumphs.

Go to Jamaica and you’ll be surrounded by signs of Scottish influence. The Scotch Bonnet pepper is a national delicacy, for goodness sake. Travel the island and you’ll drive through Culloden, Dundee, Aberdeen, Elgin, Kilmarnoch (with an ‘h’), even Glasgow again…albeit in undeniably better weather. There are, believe it or not, around 300 towns in Jamaica with names rooted in Scotland.

The planters, merchants and even enslaved people who worked the tobacco fields adopted – or were forced to adopt – Scottish surnames. A quick flick through Kingston’s telephone book will throw up all sorts of unlikely yet true surnames; McKenzie, McIntosh, Anderson, Campbell, Archibald. Sounds like the warmers who littered the Partick Thistle bench last weekend, doesn’t it? Every one is a common Jamaican surname. FACT: the most common surname in Jamaica is Campbell. Even Usain Bolt is named in relation to the Scots word for running extremely quickly. Or maybe he isn’t.

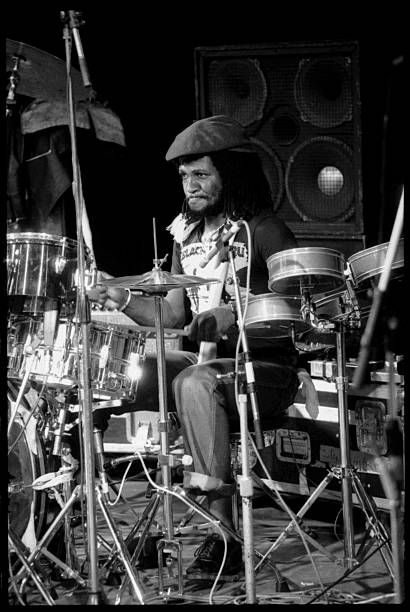

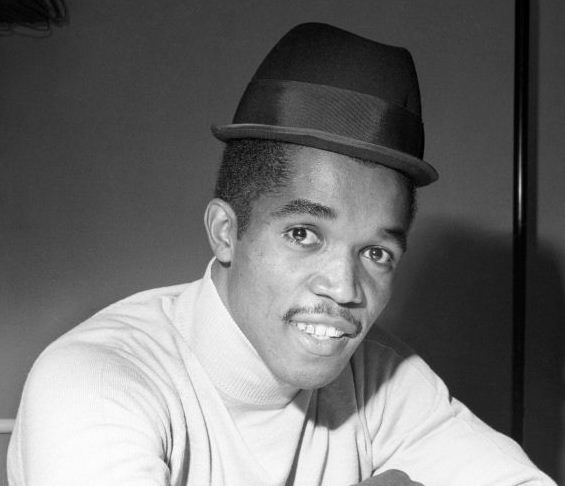

Anyway. This brings us to Sly Dunbar.

That surname has always intrigued me. How did a right-on roots rocker from Kingston end up with a random east of Scotland town for a surname?

The answer might be found in the history books. I may be adding two and two together here and getting five, but give this some thought.

We need to go back to 1650 and Oliver Cromwell’s march on Scotland to rid Charles II from the Scottish throne. Seen as a direct threat to his plans for an English Commonwealth, Cromwell and his army marched on Edinburgh. Forced back from there, they fought and quickly defeated the Scots in the nearby town of Dunbar. Around 3000 Scots were killed in the battle, with a further 10,000 marched as prisoners of war to Durham in the north of England. Of these 10,000, many died through disease and malnutrition. The survivors were thrown on a boat and sent to the colonies to work as tobacco plantation labourers. Eventually, they settled, formed relationships with the locals and had families. Which is where, I’d think, Sly Dunbar’s roots lie. It’s certainly a plausible theory.

Sly Dunbar played drums on literally thousands of tracks. A quick flick through your own collection, or even a random lucky dip, will quite possibly reveal something he drove the rhythm on. From Bob Marley to Bob Dylan, Serge Gainsbourg to Britney Spears, Sinead O’Connor to Yoko Ono, nothing was off-limits for him. Often in partnership with his bass playing sidekick Robbie Shakespeare (now, there’s another interesting surname), Dunbar provided nothing less than a killer rhythm. He could be thunderous, as he was when laying down the echoing patterns that ricocheted around Lee Perry’s many productions. He could be metronomically rickity-tickity, as he was when rattling out a hi-hat pattern on a roots reggae deep dive. He could be subtle and feather-like when required, like he was on the slow and steady Roots Train from Junior Murvin’s Police And Thieves album. Dylan’s Jokerman. Dury’s Girls Watching. Herbie Hancock’s Future Shock. Sympathetic to the song and what was required of him, he was never the star, but he was never not noticed.

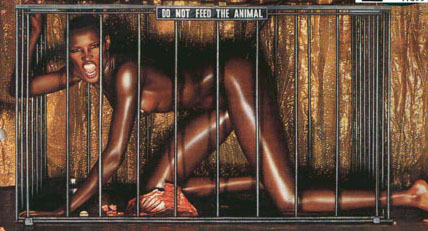

His work with Grace Jones remains a high point. Their high, skanking take on The Pretenders’ Private Life is a proper room shaker that requires, undoubtedly, immediate attention if previously unheard. The tripped out and dubby atsmosphere he and Robbie cook up on Jones’ version of Joy Division’s She’s Lost Control is insanely great, Manchester’s greyest of rainy day anthems transported bouncily to the sunny climes of the Caribbean. The nudge-nudge innuendo they play to in Pull Up To The Bumper‘s reggae disco groove, long black limousines ‘n all, is fantastic.

Grace Jones – Warm Leatherette (long version)

I’m a sucker for the long version of Warm Leatherette, Grace’s take on Daniel Miller’s debut release for Mute Records, in itself an interesting and skronky piece of early electro experimentalism, but with Sly on the drum stool, a track that’s now drawn out into a cold and detached slice of post-punk. You know those scenes in 1980s American movies, when a shoulder-padded cop stakes out the leather blouson’d bad guy in a neon-lit multi-tiered club? This track would’ve been perfect for the soundtrack.

“Waaarrrmmm!” Grace purrs. “Leather-ette!” Keyboards tooting like traffic jams, bass prowling and popping like Jones herself in a roomful of young guys, the car and its features a metaphor for the singer’s carnal desires.

Rock(steady) on, Sly.