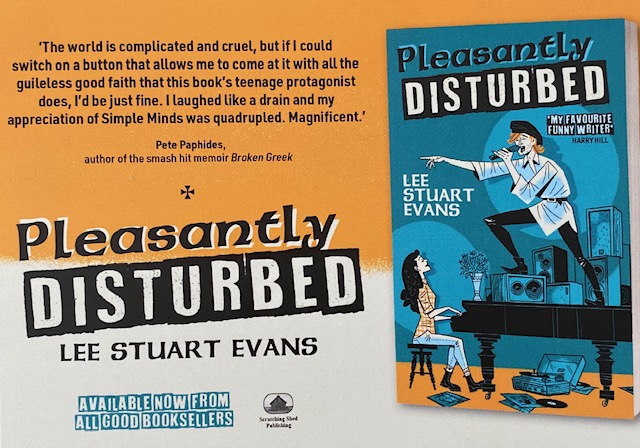

The BAFTA-nominated Lee Stuart Evans is a comedy writer of some repute. You’ve probably laughed at his jokes as they’ve been delivered to devastating effect on Harry Hill’s TV Burp, or by Frank Skinner, Julie Walters or any number of celebrity faces you’ll care to recognise on the multitude of comedy panel shows that fill the night time slots. He’s even had the honour of one of his jokes being read aloud in Parliament. A full time writer for over 20 years, Lee’s second novel Pleasantly Disturbed was published last year.

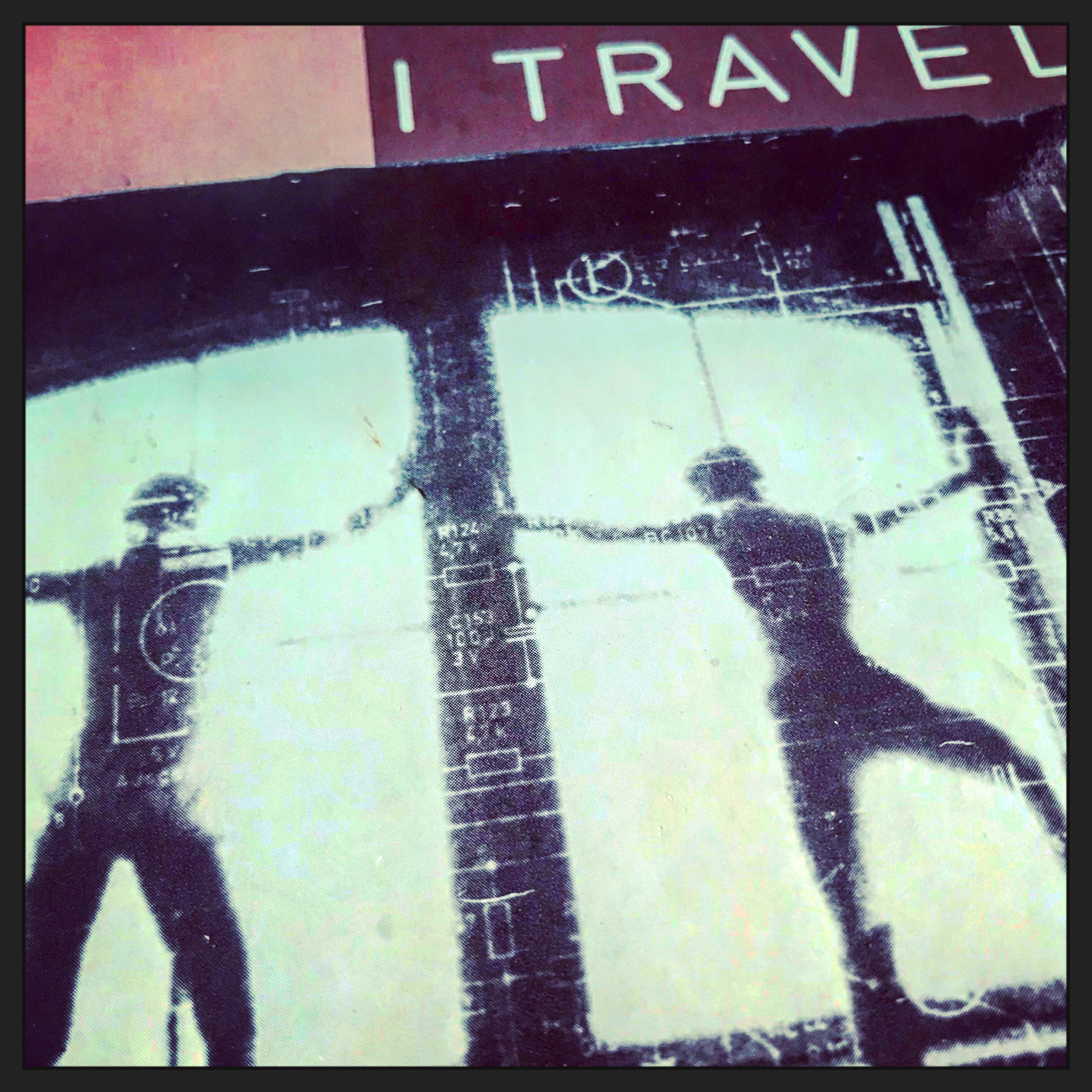

It was following a post I’d written about Themes For Great Cities, Graeme Thomson’s excellent Simple Minds biography, that Lee got in touch. Would I like to review Pleasantly Disturbed, a novel that had Simple Minds at its core?

Lee’s book arrived, along with a kind note from him, and I sat it on my ‘to read’ pile – you know that ever-growing tower of books on the bedside table? And there it sat for ages. And ages.

And ages.

And eventually I started to read it.

Then I dived head-first into a work-related Open University course which was extremely reading-heavy….and Lee’s book went back to the ‘to read’ pile again.

But this week, off work but now well enough to function on basic tasks, I picked up Pleasantly Disturbed, slightly ashamed at myself for neglecting it for as long as I had, and restarted from the beginning. I tore through it in two days. It was, to quote the Trashcan Sinatras, an easy read. The review that follows is my attempt at one of those 200-word Mojo/Uncut/Q reviews from the back of the magazine – this ain’t music, per se, they suggest, but it has music as a central theme and with you being of a particular demographic, it’s something you might enjoy reading.

Pleasantly Disturbed by Lee Stuart Evans

There’s more to life than cars and girls, as someone once sang. But not much for our protagonist Robin. Only Simple Minds gets the better of them in the holy hierarchy of life’s staples, yet all three are intertwined in a story that takes in organised crime, reality TV and the foibles of the equestrian set.

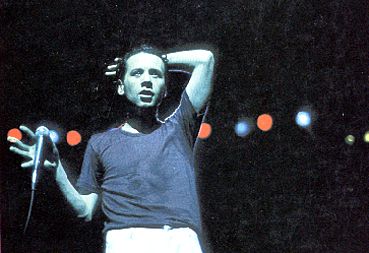

Set in the English Midlands, it finds late teen Robin Manvers (and possibly our author himself) dreaming of being Jim Kerr. ‘Divorced’ from his dad and living with his mum and sister in a shabby house, Robin needs a way out. Knowing that even the most kohl-eyed and esoteric of rock stars have to start somewhere, malleable Robin takes on an apprenticeship at a local garage. This gives him the necessary funds to buy clothes, records and tickets to Simple Minds Mandela 70th Birthday show at Wembley, a show he plans to take in with girlfriend Fliss.

Fliss comes from the other side of the tracks; she’s horsey, she comes from an extremely wealthy family and she has a Kate Bush obsession the equal of Robin’s hero worship of Jim Kerr. It turns out too that Fliss has a buried musical talent not heard since Wuthering Heights first fluttered its way into the nation’s collective consciousness – a talent that everyone but Fliss herself can see, but a talent that, should the stars align, might well take her all the places Robin can only dream of.

Fliss’s father, a golf clubbing Rotarian happens to be friends with Robin’s boss at the garage…they are similar people…they have similar business interests…a shared interest in cars… and gathering pace quicker than you can shout “Speed your love to me!”, the storyline unspools, shoots off in unexpected directions and gathers together again neatly at the end.

All the correct cultural reference points are here; the allure of Susannah Hoffs, Minder, nods to up and coming bands, the unspoken kinship with Gregory’s Girl and the films of John Hughes, and the story is told with the same fast-paced humour that Evans has developed across his numerous TV scripts. I particularly liked how the final chapter time-jumped to the present day, so we found out how everyone’s lives turned out.

If you’re looking for a page turner to while away the Easter holidays or read and re-read until Simple Minds hit their run of UK summer shows, you might want to find a copy of Pleasantly Disturbed.

You can Pleasantly Disturbed by Lee Stuart Evans in all the usual places, but especially from here.