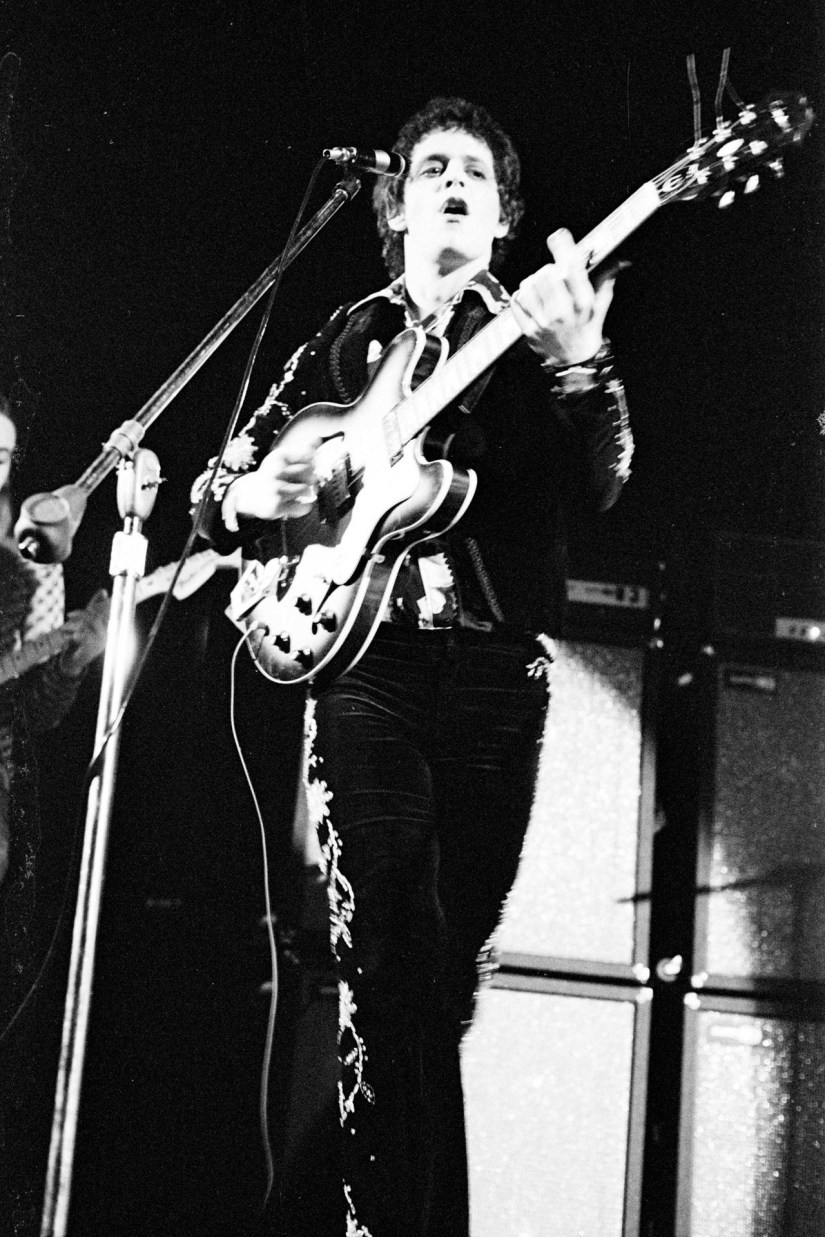

It begins with a riff as rickety as the Coney Island Cyclone, a clattering, knuckle-dusted, steel-wound nickel on wood bone-shaking rattle. Lou Reed sounds like he’s just about made it to the mic on time for those first coupla words, like he’s been so transfixed by his own instantaneous riffing that he’s momentarily tuned out of anything else and hastily ran up to it marginally late for his cue. Most other bands would clatter to a sudden halt, shout ‘Take Two!’ and fall into action again. This though, being the Velvet Underground, can be passed off as art; you noticed, yeah? Yeah! It’s deliberate and obtuse and deliberately obtuse, so what, huh? To Lou, mistakes are for lesser groups who worry too much about what their audience thinks of them. ‘You know it’ll be alright,’ as he sings in the chorus

The Velvet Underground – What Goes On

An organ drone wheezily fades its way in at the start of the second verse, subtle to begin with, vamping the simple chord changes, then a bit more prominent in the mix as the angle of Lou ‘n Sterling’s highly-strummed agit-jangle takes proper hold.

There’s a fab! u! lous! feedbacking twin guitar break – of course there is, this is the Velvet Underground – that rises from the beat group clatter like Scotch mist and surfs its way across the continuing stramash below, landing itself like a set of bagpipes being trampled to death in a crowded Turkish souq bazaar. I’m sure that’s exactly the sound the Velvets were chasing, as they say.

Elongated mid notes meld between high and low counter notes, Lou ‘n Sterling’s floating frequencies weaving as one for longer than most groups of the time would dare, but still not nearly long enough here. It’s a trippy and hypnotic garage band tour de force, What Goes On. It really is.

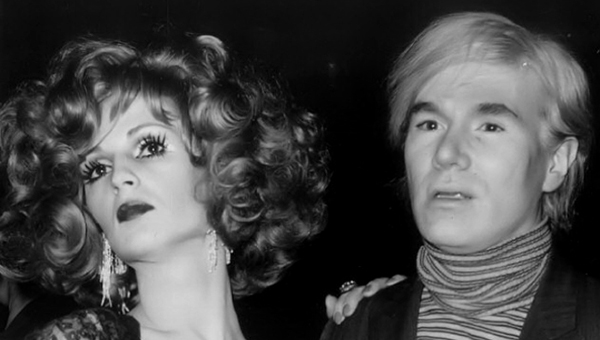

Then we’re back to the chorus, the easy, woozy harmonies adding late era Beatlish warmth to the ice-cool New York art rock. From then on in, it’s a no nonsense, heads down boogie between guitars and organ drone. The twin guitars are high in the mix, trebly and piercing, rattling away like a Warhol hopeful behind the bins at the Factory. The organ is simple and slo-mo, a relaxing counterpoint and very much the antithesis to the manic, never-ending jangle out front.

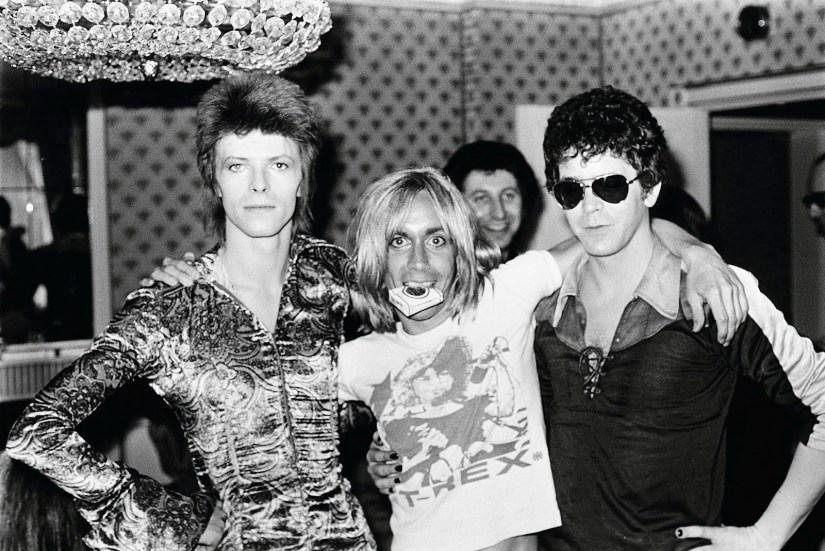

Somewhere, amongst all of this heady art-rock splendour, must be bass and drums. They must be there, right? If you listen closely – really closely – you might hear them, but you’ll need to tune out of that other strange noise in the background – that’ll be the frantically scratching pencils, as Collins ‘n Kirk and a handful of other magpie-minded guitar stranglers make sense of this motherlode of all blueprints and run with it all the way to 1980 and the land known as indie.

Influential…and then some.

Post-Script

Interesting Point 1: There’s an internet theory that the organ on Talking Heads’ Once In A Lifetime is directly lifted, if not actually sampled, from What Goes On. When you listen to both songs, there’s a compelling case for it, but I’ll leave it to you to play them back to back.)

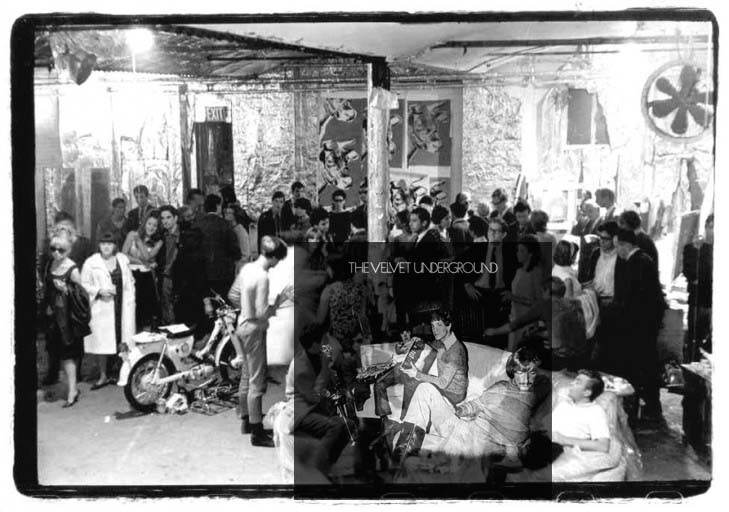

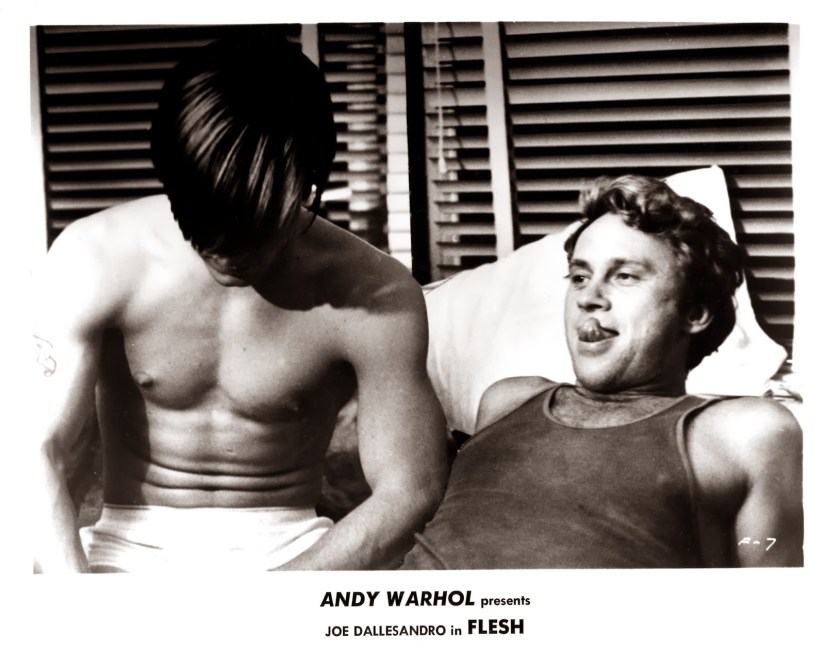

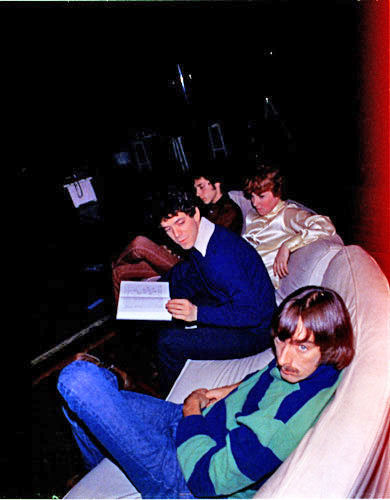

Interesting Point 2: PopSpots, that essential guide to placing your old band shots of yesterday onto the NYC streets of today has a whole section on Lou/Andy/VU’s New York. That couch that appears on the sleeve of What Goes On‘s parent album, the self-titled VU’s third, was seemingly a feature of Warhol’s factory as much as the Velvets themselves.