The impressively-named Rutherford Chang died a couple of weeks ago.

Who? you say.

What!? I retort. D’you mean you never followed him on Instagram?

It’s a fascinating story…

The son of a Palo Alto tech bigwig, Rutherford’s comfortable lifestyle allowed him to forego a normal working routine, instead affording him the time and resources to indulge in high conceptual art; taking the front page of the New York Times and, with all the news that’s fit to print, rearranging every piece of text into alphabetical order; cutting and pasting all of Asian actor Andy Lau’s numerous and varied death scenes into one near-half hour video compilation of death after death after death; editing a George W. Bush State of the Nation speech by removing all of the President’s words and leaving only Bush’s pauses, coughs, breaths, rustles and the crowd reactions in place. Crazy and interesting stuff like this.

A chance teenage purchase of a second-hand Beatles’ White Album in the late ’90s would lead him to his defining concept, one which would bring his name to a wider audience and one which would allow him to fully indulge his need for order, ranking and system within his particularly niche world.

(When I get to the bottom I go back to the top of the slide.)

A while after buying that Beatles album, and noticing that a second copy of the same record in another shop had aged differently, Chang had the masterstroke of all conceptual ideas. He bought that second copy of the White Album and right there and then began to obsessively gather as many copies of the record as he could. He advertised locally. He trawled record shops. Or stores, as he’d no doubt call them. He pored over Craig’s List. He sought out garage sales. And gradually, he amassed an impressive array of White Albums and only White Albums.

(Where I stop and I turn and I go for a ride.)

Battered, bruised, bashed, beat up, the more so the better. Those copies had more life in them, more unknown stories to tell. Chang was interested in how something that began life so white and pure – and mass produced – could end up discoloured, written on, stained and unique. The journey each record and it’s sleeve had taken was just as important to Chang as the music that filled their grooves.

(Till I get to the bottom)

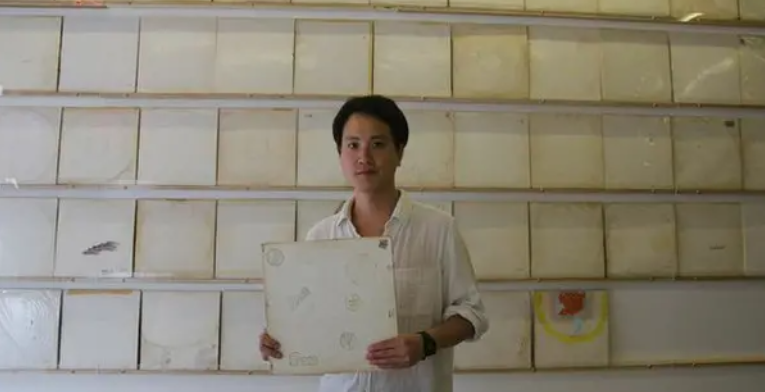

“There are three million of them out there,” he said cheerfully in 2013, by which time he owned nearly 700 copies of the album. He played them all too. He set up a gallery space in New York’s Soho, recreated the feel of a classic record shop, stuck a ‘We Buy White Albums’ neon sign in the window and, when he wasn’t bartering with potential sellers, allowed gallery visitors to browse his ‘racks’, select a copy and stick it on the in-house turntable.

It was clear that, as they spun, some of his acquired copies were beautifully pristine. Some sounded like bacon and eggs frying down a well. Some jumped. Some stuck. Some were stereo copies. Some were mono. But all were versions of the same record.

(and I see you again

and again

and again

and again

and again

and again)

By 2014 – a year later, Chang had collected over 1000 copies, buying on average one copy a day since 2013. And, like the most diligent of museum collection curators, he meticulously catalogued them all. Where he’d bought it, how much he’d paid for it, what the stamped number on the front was, was it a mono or a stereo, a first press from the UK or a third press from the US, a seventeenth press from the Phillipines? And once catalogued, the records were displayed in his gallery. Dividers were slotted into bins, arranging the records by serial number or origin or year. Just like a real record shop, only different; this collection was a record of White Albums and the stories they held. Wouldn’t you just love a browse through them all?

He had a rule – hard to believe in 2025 – that no copy should cost him more than $20, but I’m not sure how steadfastly he managed to stick to that rule. He had some pretty low-numbered and interesting copies in there and, regardless of the state of any of them, I’ve sure never been lucky enough to upturn a copy of the record – mono, please, a toploader…with all the inserts, thanks – at anything under three figures. The one I found by chance in a box of records in New York’s Chelsea Market flea sale was a snip at a cool $599 and it looked like it had been well-loved, to be kind to it.

Even my bog standard ’80s reissue (yeah, it has the poster and the four portraits, as well as two slabs of well-looked after stereo vinyl) would fetch £40 on the current second-hand market. Not that Chang would’ve been too keen on securing mine. I appreciate he was all for securing copies that had seen a bit of life but, as long-term readers here may know, I drunkenly relieved myself on my prized copy on the night of my 18th birthday. Some of Rutherford’s copies had coffee stains. Some had food stains. Light brown pish stains though, the colour of an earthy Farrow And Ball paint chart? And this is none of your Greenwich Village hippy stoner pish either, I’m talking primo McEwan’s Lager pish stains from the west of Scotland. I bet Chang never had a copy quite like that. Bog standard, by the way. Pun intended.

What Rutherford did have was plentiful and interesting enough that his collection would travel to Liverpool to be shown in the city’s FACT art gallery. There, visitors could browse what was undeniably the largest collection White Albums in the world. Sleeves with scribbled names. Sleeves with love letters falling out of them. Sleeves with break-up letters inside them. Soft drugs, soft porn, money… sleeves teeming with the minutae of life. Sleeves teeming with the minutae of life, safeguarding one of music’s most important artistic statements. High concept art.

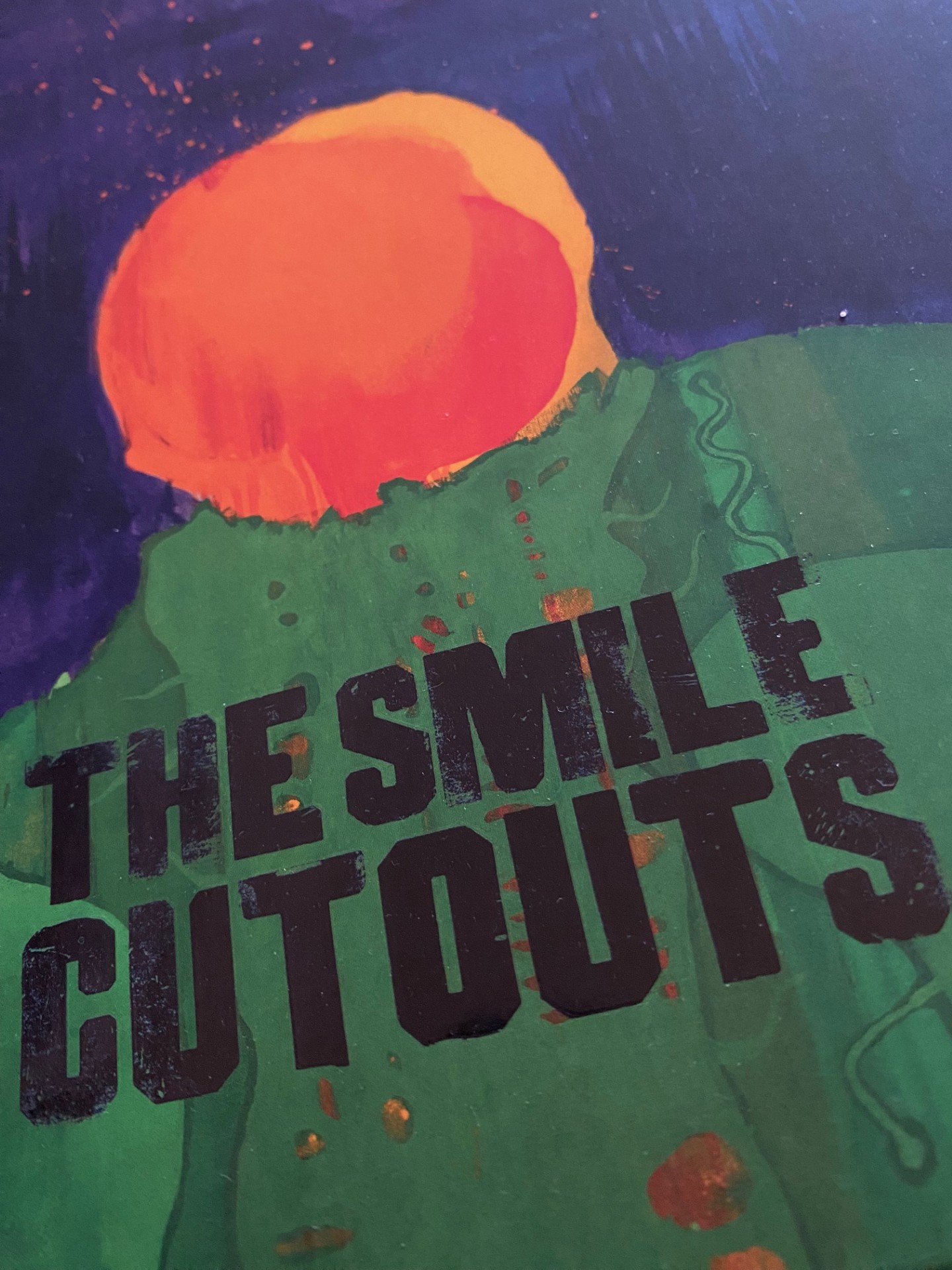

To accompany his travelling exhibition, Chang took 100 copies from his racks and did two things.

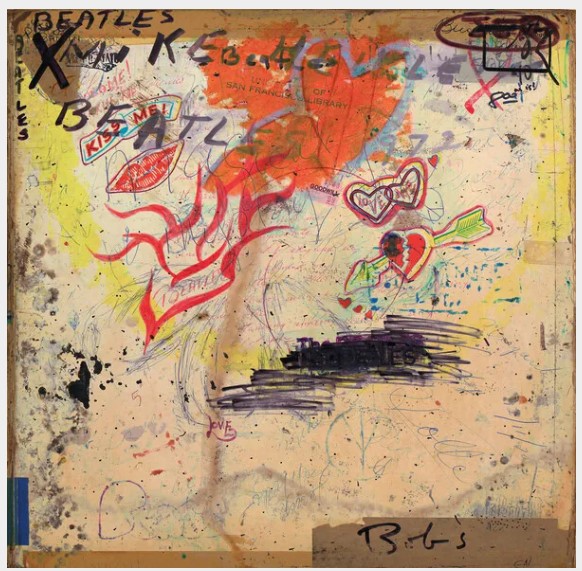

Using trick photography, he superimposed all of the 100 sleeves on top of one another to create a master sleeve that was anything but pure white. In its own way it’s a unique work of art.

He then took those same 100 records and built a wall of sound of the 100 records playing simultaneously. Due to a number of contributory factors; where the needle dropped, the minute variations in belt drive speed of the turntables, the gaps between the tracks themselves (micro seconds of a difference, if at all, but multiply that by 100…), Chang unwittingly produced? built? a proper slice of arty, woozy psychedelia that the Beatles themselves, and indeed, Yoko Ono, would’ve been proud of.

The delay-lay-layed way in which Dear Dear Prudence fades in on Back In The USSR‘s roaring jetstream…Glass Onion‘s sandpaper rumble and oh yeah-yeah-yeah- oh yeah-yeah-yeahs…, Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da‘s jittery and jangly piano intro (la la la la life goes on…and on…and on…) …the compressed mayhem of While My Guitar Gently Weeps-eeps-eeps…that bleeds into Warm Gun…Warm Gun Warm Gun…Yeah…Yeah…Yeah…Yeah… It makes for an interesting, occasionally unsettling (and possibly just once in a lifetime) listen. I wonder what Charles Manson would’ve made of it all.

At the time of his death two weeks ago, Rutherford Chang had amassed almost three and a half thousand White Albums. He was only 45 and had many more years of collecting ahead of him. I wonder what happens to the records now? Does someone take the project on? Do the people who sold them to Chang in the first instance get offered a chance to buy their copy back for the $20 they were paid? Rutherford’s detailed records will, after all, have all the necessary contact info. Or, does someone sell them all and rake in a whole load of money? I’m keeping a keen eye on things from over here.