Plain Or Pan turns 19 today. One blink, and already, it’s into its final year of being a teenager, somehow mid-way through second year at University and making its own considered path in life. It’s very much its own thing these days, with its own mind and opinions and world view. Unlike its curator, gone is the need to be on it all weekend…unless by ‘on it’ you mean gym equipment. It’s protein, not pints for this one, and it looks good for it. Will it wish it had done more reckless things in its late teenage years? I doubt it. So far, it seems quite happy in its own skin. Let’s see how it fares in its 20th year – all things considered, it’s not bad going for a wee music blog steadfastly stuck mainly in the past.

Talking of which…

I’ve been reading Colin MacInnes’s Absolute Beginners the past week. On Paul Weller’s say-so, I’d tried it years ago, more than once, but couldn’t get with it so sat it aside and let it gather decades of dust. I’m glad the urge took me to pick it up again. Something clicked. It hooked me and I read it in three nights flat. It is, as it turns out, a terrific book; fast of pace, meaty in subject matter and, when the protagonists are in scene, written in a sort of secretive teen-speak that could give Anthony Burgess’s nadsat argot in A Clockwork Orange a decent run for its money. I suspect you knew this already though.

Set in 1958 (and published hot off the press in 1959), it tells the story of a 19-year old west London teen, moved out already and living in a run down yet vibrant multi-cultural area. His neighbours are prostitutes…druggies…violent Teddy boys…beautiful people of all sexualities; it all makes for an obscene melting pot of edgy living. A hustling freelance photographer, we never find out his name – as he comes in and out of contact with the other key characters, he is referred to as ‘Blitz Baby’, ‘the kid’, ‘teen’, and so on – and we follow him as he falls out with his mother, takes a trip with his dying father and tries to convince his once girlfriend – ‘Crepe Suzette’ – not to settle for a marriage of convenience with a much older gay man. Race issues boil over – a result of a campaign of hate by the Daily Mail (or Mrs Dale, as the young folk refer to it) and our photographer is caught up in the melee of the Notting Hill riot, his head clobbered, his Vespa stolen, an easy target on account of his friendship with the Indian and Jamaican communities.

Jazz speak falls from every page, in-the-know references made to late-night Soho establishments where modern jazz is the new thing, where style-obsessed teens pop pills and seek thrills, the first generation post-war to grow up in a technicolour world where hope, ambition and aspiration are the key factors in eking out a life as far removed from your parents’ as possible. Nineteen, with a bit of cash in your pocket? And an attitude? And a way of speaking that is alien to the generation that came before you? You’re an absolute beginner.

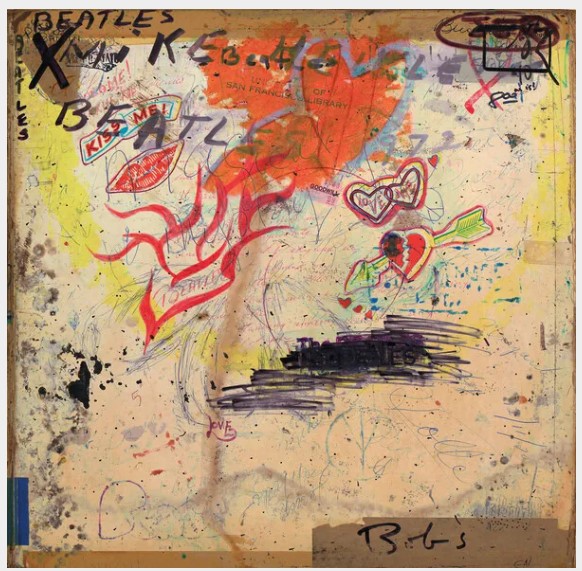

The 1986 film adaptation of the novel has, since its release, come in for a fair bit of well-deserved and sometimes misguided stick. Even David Bowie’s majestic theme song – and one of his very best – can’t quite save it entirely, nor the sight of him turning up as slick advertising exec Vendice Partners in the sort of suit (if not accent) he might’ve adopted as stage wear towards the end of the decade. Like most adaptations, the book is far better (the film feels the need to name our absolute beginner ‘Colin’ – in memory of the novel’s deceased author, you have to think) but in the montage below there’s some great film-only dialogue, between the vibraphones and shuffling snares, brightly-coloured sets and hammy accents, that’s worth bending your ear towards.

*One point for every cast member you can name in the clip.

‘Aren’t you a little too old for her?’

‘I’m only thirty-seven…’

‘Thir’y seven?! Arahnd the waist, maybe..!’

(Also – doesn’t the Bowie track that plays at the end owe more than a little to Madonna’s Material Girl? A tongue-in-cheek reference maybe, given the subject matter of the scene being soundtracked?)

Paul Weller called Absolute Beginners ‘a book of inspiration’, so much so that he ‘took’ it with him as his only source of reading material when he was banished by Kirsty Young on Desert Island Discs. If you are an impressionable teenager looking to find yourself and choose a path in life, the novel, with its themes of socialism and left-wing politics married to a decent soundtrack is a fine place to start. Weller would, of course, name a Jam track after the novel and later in the Style Council would create a tune called Mr Cool’s Dream, a reference, I’m assuming, to the character of the same name in MacInnes’s novel.

Weller was called upon to provide music for the film and so, drawing on his love of Blue Note and off-kilter time signatures, he came up with the bossanova boogaloo of Have You Ever Had It Blue?, a track that still has a comfy place in his setlist even to this day. And why not?

The Style Council – Have You Ever Had It Blue?

And here’s Our Favourite Shop‘s With Everything To Lose, the, eh, *blueprint for the above track.

Footnote:

Have You Ever Had It Blue?, as groovy and finger clickin’ as it undeniably is, *owes more than a passing resemblance to the horizontally laid-back sunshine soft pop of Harper & Rowe‘s 1967 non-charting (and therefore obscurish) The Dweller. It’s certainly the best Style Council track that Paul Weller didn’t write. Perhaps, for this track, Weller should’ve renamed his group The Steal Council and come clean about it.

Harper & Rowe – The Dweller

*in the clip:

As well as the obvious; Ray Davies, Alan Fluff Freeman, Patsy Kensit, Ed Tudor Pole, Lionel Blair, Edward ‘father of Lawrence’ Fox, Sade, Stephen Berkoff, Slim Gaillard, Smiley Culture, Bruno ‘Strictly’ Tonioli, Robbie Coltrane, Sandie Shaw, Mandy Rice-Davies…quite the cast, eh?

**maybe not all in the clip (!)