There’s the clip in Spinal Tap when Nigel Tufnel, all Jeff Beck hair and street punk gum snap, is showing off his collection of vintage guitars. He holds up a Les Paul (of course) – “s’a ’59” (of course) – and, as the interviewer asks him the value of the guitar (of course), Tufnel butts in and implores the interviewer to be quiet and listen to the sustain of his unplugged guitar.

“Just listen…the sustayn…just listen to it…it’s faymous for its sustayn…eeaaaaaaahh…”

It’s ridiculous and smart and very funny, with Christopher Guest playing it straight and just on the right side of dumb but rich Londoner, and with much of Spinal Tap being cribbed from stories involving real-life musicians, you wouldn’t bet against this being a true story too.

Is it a myth that old guitars sound better? Apparently not. Or maybe that should be apparently knot. Old guitars sing with the release of being played again. It’s a fact. Scientific too.

The science of it all (usually a subject that has me passed out and horizontal in under a minute) decrees that as wood ages, the sap in the wood dries out. So the more the guitar is played, the more the wood vibrates, y’see, and it’s those vibrations that help to speed up the drying out process. It stands to reason that an old guitar that’s been well played – a ’59 Les Paul, say, or my own ’78 Telecaster (most definitely well played rather than played well) – will indeed have a more cultured and refined tone than one that’s just straight from the luthier’s workshop.

Acoustic guitars tend to have a more noticeable improvement with age. There’s no pick-ups for starters, so the sound is made at the source rather than via amplification, and the instrument’s hollow body helps that sound to resonate. The wood the guitar is made from (and that could be alder, mahogany, ash, elder, a combination of some or all…) and the tension of strings used and how regularly it’s been played will all affect its overall tone.

When my dad passed away I inherited his Lag acoustic guitar. It wasn’t a particularly expensive guitar and it wasn’t that old when I fell heir to it, ten years maybe, but the old folkie (and that’s a story in itself) had treated it well and played it regularly enough (at gigs – I told you there was a story) that playing it is a proper joy. The action is low and smooth. There is no fret buzz. The bass notes are rich and reverberating. It handles the capo at the highest of frets, happily stays in tune and it responds really well to Keith Richards open G tuning. Best of all, what I’ve found if I tune it a whole step down, is that it sounds bassy and bluesy and bendy and exactly the sort of pitch and frequency that might have someone like Lee Mavers getting a whole set of songs from.

I’ve kept it in this tuning for over a year and there’s rarely a night when I don’t pick it up for a bit – anything from a few minutes to a few hours – and play it, the dusty ghosts of my dad’s fingers, just below my own, spidering up and down the fretboard and dancing across its six strings as I get to grips with a tricky Johnny Marr passage or a pastoral McCartney number or, this week, The La’s Son Of A Gun. Down-tuned and loose and funky, there’s enough give on the strings to give it soul, enough open strings in the picked verses to ring out naturally between the rhythmic off beats played by the right hand’s finger nails on the scratchplate and enough bass to make the strummed chorus full of fat and full of flavour. Unsurprisingly, The La’s version is also played in this tuning; the tuning of humming fridges and ’60s dust and the Merseyssippi and single bloody mindedness. Look long enough around this blog and you’ll probably find it.

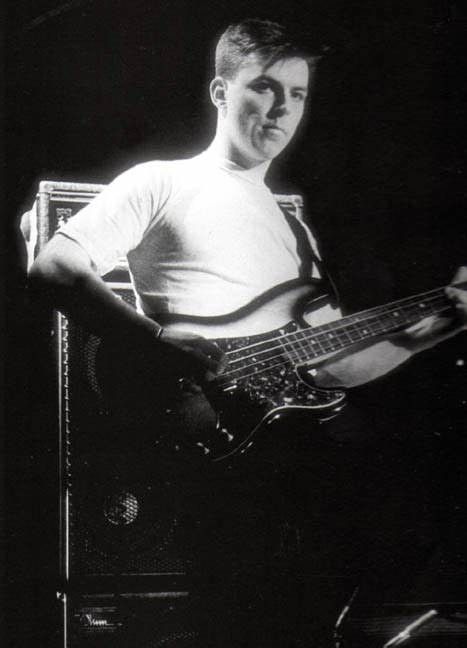

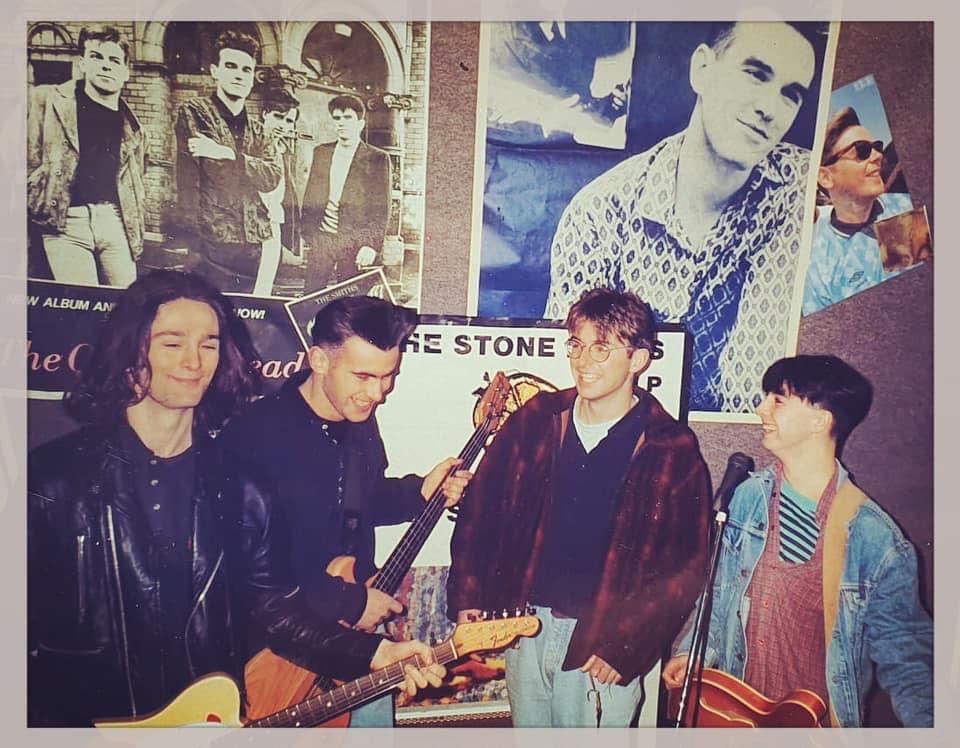

Another guitarist more known for his skewed Telecaster playing than anything else is Blur’s Graham Coxon. He’s a great player too, happily chopping out punkish riffs and wiry leads and art-pop, rule-breaking bridges, employing two Rat distortion boxes simultaneously to devastating effect. What’s perhaps less-well known is that he’s also a fantastically accomplished acoustic player.

Graham Coxon – Sorrow’s Army

Sorrow’s Army from his 2009 Spinning Top solo album conjures up the spirit of Davy Graham and rattles its way out of the traps like Mrs Robinson on speed, strings snapping tautly – he favours skinny ones, a 9 gauge after some advice from Bert Jansch, every finger on his right hand employed in blurry syncopation, left hand shifting through 7ths and minors with dextrous ease, the squeaks and scrapes of flesh and nail against the strings adding fireside warmth. It’s not Girls & Boys or Popscene or Beetlebum, but when the song’s clattering Magic Bus rhythm announces itself around the minute mark, it all falls into place. The accompanying album is worth investigating too, should this be your kinda thing.

Old guitars, handed down, played forever. Now there’s your sustain-ability. Just listen.