A film. Bleached out print, grainy in places with muted, filtered, Instagram-to-the-max colours; subtle mustards, pale yellows, murky beige, an occasional dazzling flash of suppressed ochre. The script is suitably gritty and realistic. Adapted from a forgotten and long out of print novella, the producers have secured the services of the era’s hottest shot; a Harry Palmer/Michael Caine type, perhaps, to lead the line and provide the necessary look that’ll pack out the Locarnos and Empires. Tough guy for the boys, eye candy for their dates, all marketing bases covered. The soundtrack is, of course, spectacular. Seven sharp and sudden stabs of brass and away we go. But more of that later.

The key scene – the one that’ll be quoted and re-enacted and ripped-off in tribute down the years – begins with a car chase. The car in front is an open top Triumph. Of course. It is flame red with silver spokes that glint in the low northern winter sun. Driven erratically and far too quickly, its back end swings out as it takes a bend at top speed. While its driver drops a gear to compensate – we never see his face, but it’s the late 60s, so we have to assume it’s a ‘he’ – the leather driving glove would back that up – an oncoming Hillman Minx is forced to swerve. It briefly mounts the pavement, causing a man in a bowler hat to jump backwards. His folded broadsheet falls from under his armpit. A woman pushing a Silver Cross pram stops further down the street, taking in the scene in disbelief.

The car behind the Triumph is a midnight blue Jensen Interceptor and unsurprisingly, it is gaining on the Triumph. The Jensen’s driver has gritted teeth, slightly yellowing, even for a movie star, (and uneven too), that chew on a thin toothpick as he drives. His thick, black-framed glasses fill his handsome face and now and again the camera picks up the reflection of the Triumph in front. Steel blue eyes unblinking, the driver focuses on his prey, mentally calculating how quickly it’ll be before he’ll reduce the gap to zero. The Triumph makes a sudden and unexpected veer to the right, the screech of its tyres heard faintly above the roar of the Jensen and the accompanying soundtrack – momentarily switched to a frantic, four-to-the-floor bass and drum beat, with the tune’s signature brass no more than a short, sharp, intake of breath away.

Gears are changed, oncoming traffic is slalomed around and we’re suddenly in a multi story car park. The Triumph in front is always just disappearing around one of its tight, whitewashed corners, the metal buffers buckled and scraped, warning signs to the dangers of driving above the recommended 5 mph, but the Jensen never loses sight of, or distance, on him. The Triumph will get to the top floor and have nowhere else to run, and our hero in the Jensen knows this. He will happily drive upwards and onwards and wait for his inevitable moment.

But hold on! The driver of the Triumph is getting out! He’s abandoned ship around the next turn and left the door open in his haste to escape. The Jensen driver just catches sight of him as he runs off, a briefcase clasped across his chest and held in place with one arm. The Jensen immediately pulls up into an empty space – the multi story is deserted, of course – it’s probably Sunday – and the lead actor – the tough, the guy eye candy – sets off in pursuit. The man with the briefcase has entered a staircase and our man follows. Briefcase guy takes the stairs two at a time, the belt buckles and tails of his tan Mackintosh billowing behind like sails, the drag factor slowing him down. Just behind, our man, dressed (of course) in a sharp two-button mod suit, remains hot on his heels. His matinee idol hair, generously lacquered to his scalp, remains immovable. Even the windswept quiff is stiff and unswaying. His glasses stick firm to his face. The toothpick too is still clasped between those gritted teeth. He’s not even broken sweat. The bass guitar on the soundtrack pulses with Cold War dread, all der-der-duh-der-der boogie-woogie spy theme menace, each beat thudding out with every step on the staircase. This music actually seems to spur the Triumph’s driver on. Is he getting away from Harry Palmer/Michael Caine? I think he is. Is he?

Is he heck.

We catch a glimpse of our lead actor’s watch – an Omega, naturally – as his left arm stretches out and the leather driving glove tap-tackles his quarry. The man in front slides ungracefully on the stairs, the leather soles of his shoes suddenly unsuitable for hot pursuit, and he tumbles awkwardly. The Mackintosh opens wide as his hand falls from across his chest. The lining – Burberry – flaps wildly as the briefcase clatters to the floor, bursting open and sending a snowfall of classified documents down the spiral staircase; blueprints and Eastern European-language papers that sashay and helicopter downwards in slow motion, a total contrast to the franticness of the cars and their runners just moments before.

“Suddenly it struck me very clear…” sings the vocalist on the soundtrack. Has the volume turned up a notch? There’s no dialogue, but you can hear the breathless grunts of the two actors as they slip and slide and tangle and detangle and ankle grab and kick loose on the metal stairs, a sinewy keyboard line snaking between their huffs and puffs. The contents of the briefcase, by now strewn across the floor, provide another slippy surface – “They can’t have it, you can’t have it, I can’t have it too…” – but Palmer/Caine/the goodie has rumbled and wrestled the Triumph-driving baddy into a corner. As the Locarno crowd go wild for their champion, he pulls (from nowhere) a set of handcuffs and fixes the villain of the scene to the metal hand rail of the stair case.

“Make y’rself comfy, princess,” he sneers, toothpick jiggling up and down with each East London phoneme he spits. “The boys’ll be round in a bit to ‘ave a little word.”

The scene cuts. He’s back in the Jensen, roaring out of the brutalist car park, its dull putty-white concrete backdrop showing off the Jensen’s cool midnight blue finish. Our main man rolls down the driver’s side window. He spits out the toothpick before leaning his right arm on the windowsill. The music picks up again, the tune’s 7-note horn refrain and thumping rhythm section taking us home. “Until I learn to accept my reward.”

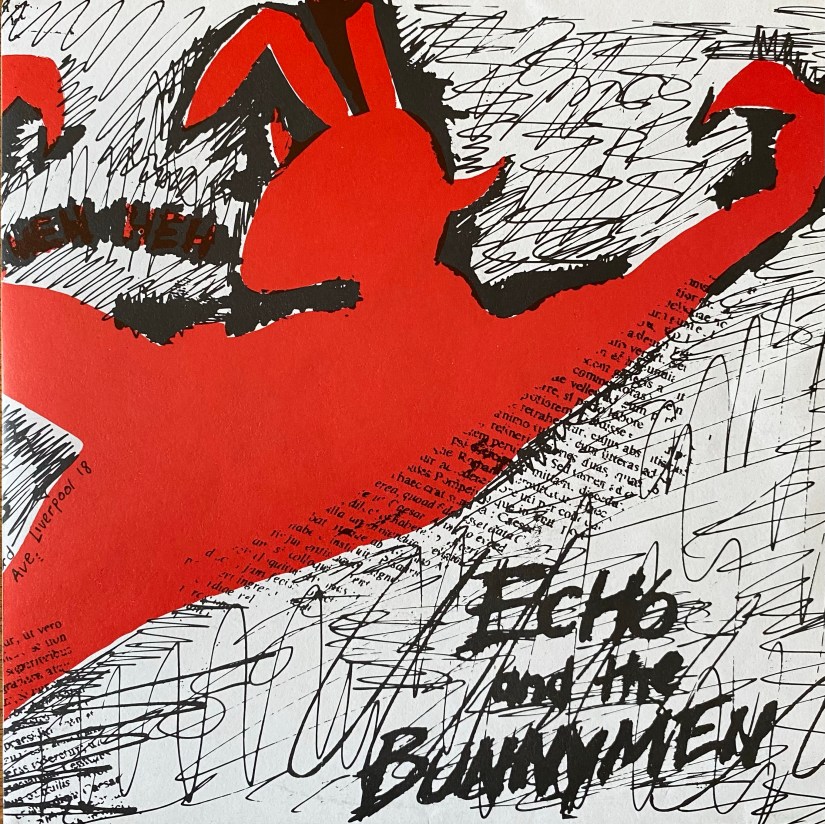

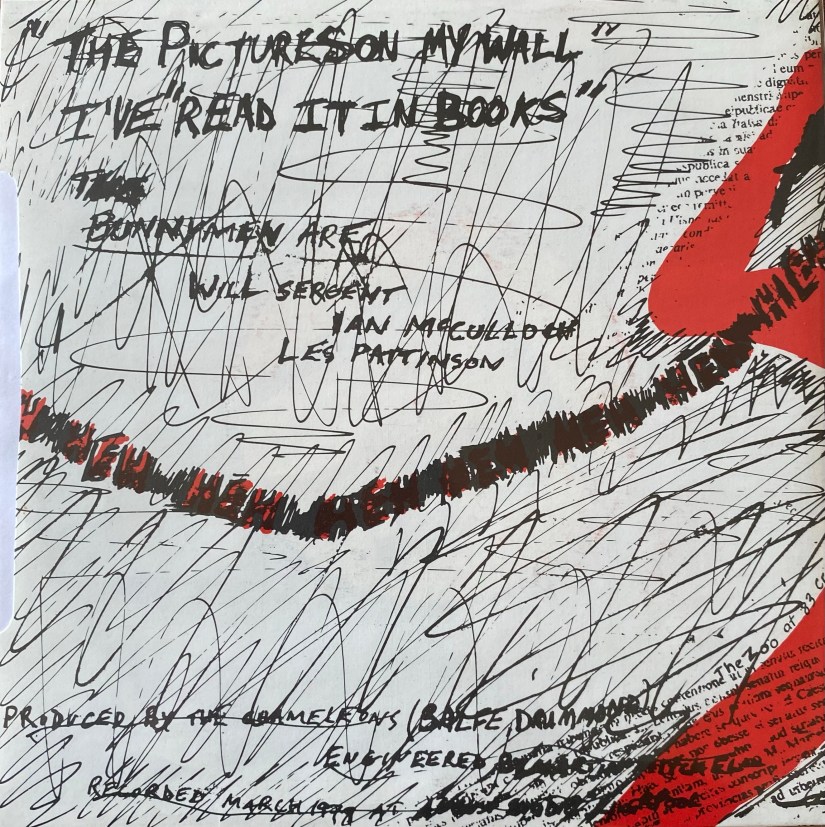

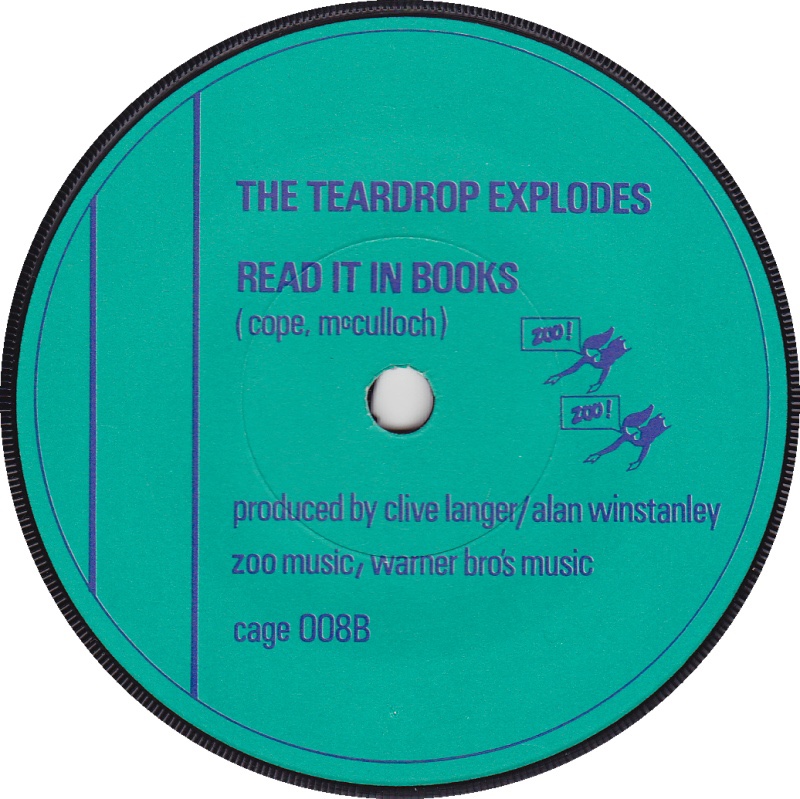

Teardrop Explodes – Reward

Julian Cope wanted Reward to sound like a long-forgotten spy theme played by the mariachi trumpets from Love’s Forever Changes LP. He fairly succeeded. And then some. Play loud, as they used to say.

Any directors needing a scriptwriter and/or music synch guy…hit me up, as they say nowadays.