Ach. Shane MacGowan. The literate libertarian and rabble-rousing romantic has drunk and sunk his last pint. Drink up, shut up, last orders. Time gentlemen, please.

When those pictures appeared a week or so ago showing a frail Shane propped up in bed, visited by pals and barely able to smile for the camera, it reminded me of the last days of my dad’s life, of his pals dropping in to say their final, unsaid goodbyes, of big grown men leaving the house in tears. To be honest, the pictures of Shane made me feel uncomfortable, unnecessarily voyeuristic, but for anyone who’s watched a loved one slip away, those candid snaps were an obvious foreshadow of what finally arrived at the end of the week just gone.

Like many, I’ve binged myself on The Pogues since the news of his death broke.

I first heard of The Pogues in 1985, and only because I turned up to participate in a Bible quiz being held in an upper room of Kilmarnock’s Grand Hall. (That story has been told on here before.) It wouldn’t be long until I properly heard the MacGowan voice, that very same night, as it goes, bellowing up in fluent MacGowanese from the floor below, in-between the stuffy quizmaster’s boring questions.

“In which book of the Bible did…”

“ahve been ssspat on, ssshat on raypedandabyooozed…“

“…Daniel encounter…”

“Sackafackazzzzhzzzzyoubastardzzz!!!“

“..a Lion?”

(Thump, clatter, diddly-dee, stomp, stomp, stomp.)

By the end of that week I owned Poguetry In Motion and never looked back.

The Pogues’ Christmas Barrowlands shows, especially the one with Joe Strummer joining them for Clash songs, were some of my favourite-ever gigs. After the Strummer one, I nearly fainted through heat exhaustion from non-stop jumping about in a very crushed and over-sold crowd. A medic made me sit against the wall of the stairs on the way out until I’d recovered, necessitating in a mad sprint back down the Trongate and Argyle Street for the last train. By the time we’d made it, my old suit jacket was stiff from frosty dried sweat. Thawed out on the train home and back at my house, it was a stinky, soggy, shapeless mess. I hung it in the shower to dry until the next morning, when I shook out not only Joe Strummer’s actual plectrum but enough crystalised sweat to keep Mama’s chip shop in salt until the next Pogues show. Memories, as the song goes, are made of this.

By chance last night I stumbled across Julian Temple’s fantastically revealing ‘Crock Of Gold’, a two hour documentary on the life of Shane MacGowan. Culled from old interviews, both film and audio, with archive footage of Irish life and additional filmed segments from three or four years ago, it’s an absolutely essential watch and a key insight into the life and psyche of MacGowan.

Shane’s ability to romanticise the unromantic is there right from the start. Reminiscing about his early years in Tipperray, he talks about the “sepia-brown farmhouse where they pissed out the front door and shat in the field out the back….” In a series of torn and frayed photographs, the MacGowan clan is shown to be tight-knit and stern faced, the wire-thin men in flat caps, faces lined like cartographic maps of rural Ireland, the handsome-faced women with arms folded over necessary pinafores.

His upbringing was equal part prayer and profanity. “Fuck is the most-used word in the Irish dictionary,” he says. His uncle educated him on Irish history and its peoples’ continual fight, a subject that would permeate much of his songwriting. His auntie Nora too was a major influence on him, introducing him to stout and snout at the age of 5 or 6, just before the family would move to England. By the time Shane had been integrated into the English school system, he was a two bottles of stout a night veteran of the stuff.

The family hated England. Despite his dad’s decent job, they were bog Irish. Thick Paddies. Outsiders. Shane rebelled. In the film, his dad notes with disdain the very moment Shane went properly off the rails.

“It was that Creedence Clearwater Revival,” he spits quite unexpectedly, in a tone normally reserved for discussing who might’ve nicked that morning’s milk from the doorstep and ran away.

Youthful dabbling in substances followed, expulsion from school not long after, with psychiatric electro-therapy just around the corner. Forever the troubled outsider, Shane found his calling in the filth and fury of punk. “I was the face of ’77!” he quips, before lamenting the movement’s inability to truly change the world. “All that we had left at the end,” he laments, “were brothel creepers, a few bottles of Crazy Colour and the dole.”

He’d discovered what a life in music might offer though, and set out to change the way Irish music was viewed. “Everyone was listening to ethnic music, so I thought, ‘Why not my ethnic music?’” The Pogues were born and the songs, poetic and proud, educating and enlightening, soon had an enthusiastic following. When asked how he goes about writing a song – “Can you write sober?” asks an interviewer at one point – Shane states that the songs are floating in the air – “that’s why they’re called airs,” he reasons, and that he reaches out to grab them “before Paul Simon does.”

The Pogues – A Rainy Night In Soho

Could Paul Simon have written a song as sweeping and grand as A Rainy Night In Soho? Or The Broad Majestic Shannon? A song as political and hard-hitting as Birmingham Six or Thousands Are Sailing? A song as simple and melancholic as Summer In Siam or Misty Morning, Albert Bridge? A song as joyful and carefree as The Body Of An American or Sally MacLennane or Sick Bed Of Cuchulainn or Streams Of Whiskey? Of course he couldn’t. No one could write songs like these ‘cept MacGowan. From waltz-time bawlers to night time weepies, he covered all bases.

You’ll hear Fairytale Of New York – “Our Bohemian Rhapsody” a lot in the coming weeks. Nowt wrong with that, of course, but I’d like to direct you to an essential source of one of its ingredients.

Ennio Morricone – Deborah’s Theme (Overture)

Ennio Morricone’s Deborah’s Theme, from Once Upon A Time In America, is slow and stately, majestic and magnificent. Shane thought so too, making good use of the motif that he’d write – ‘It was Christmas Eve, babe/And then we sang a song/God, I’m the lucky one‘ – across the top of. A powerful, beautiful piece of soul-stirring music that gave rise to another.

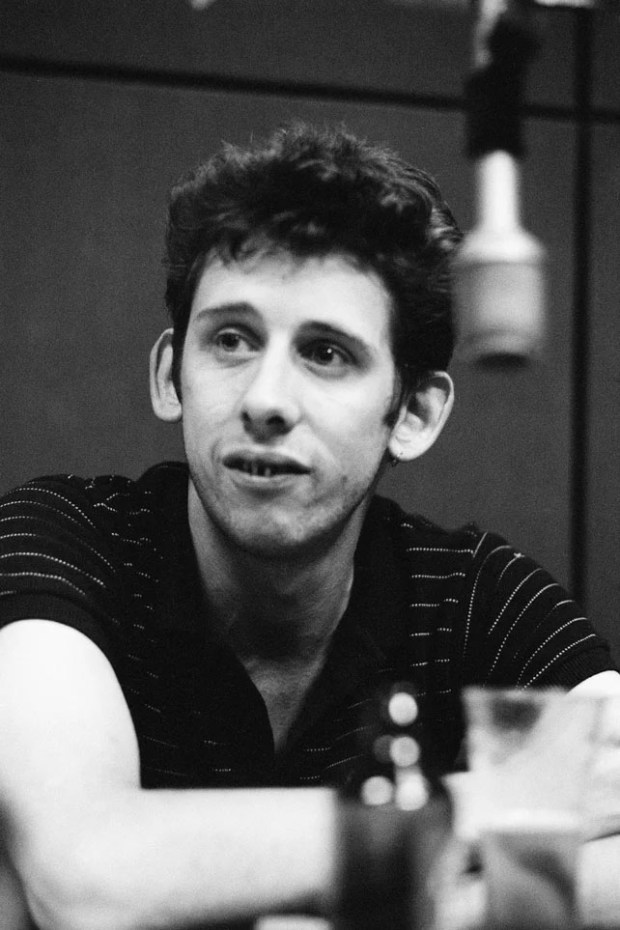

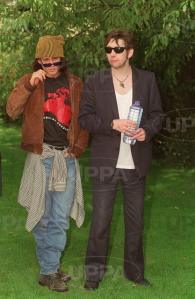

Shane Patrick Lysaght MacGowan (25 December 1957 – 30 November 2023)

One of the greats.