There’s a decent case to be argued for Paul Weller being England’s equivalent to Neil Young. Both started young and both found instant success with their first real bands – Buffalo Springfield in Young’s case and The Jam in Weller’s (like you didn’t know already). Both these bands released era-defining tracks and tapped in to the consciousness of youth. And just as Young left Buffalo Springfield to forge a solo career packed full of instantly-regarded classic albums, side steps peppered with choice collaborations and sudden left turns towards new and unexpected musical directions (the ‘Ditch Trilogy‘, Trans), Weller too defiantly broke new ground, alienating some fans, richly rewarding others, side stepping his exquisitely-shod feet through the decades with interesting and quirky one-off collaborations and the odd soundtrack thrown in for good measure. Weller, like Young, lives, breathes and drinks music. He creates seemingly every day, tours regularly and (unlike Young nowadays) releases albums with a high quality control and impressive frequency that suggests if he doesn’t get them all out of his system as and when they’re ripe for recording, he’ll wither and die. Prolific? Paul Weller is the very definition of the word.

In 1989, the Style Council was coming to an end. The law of diminishing returns coupled with a changing musical climate saw to it that only Weller’s most enthusiastic fans were still with him. The pop charts may have been filled mainly with total rubbish (Jive Bunny, New Kids On The Block, Jason Donovan) but the underground was bubbling up nicely. Happy Mondays and Stone Roses were a Joe Bloggs flare flap away from ubiquity. Effect-heavy guitar bands were filling a post-Smiths void. Acid house and electronic dance music was soundtracking sweatboxes and switched-on clubs, yet still to be sanitised for the mainstream.

Weller, ever willing to embrace the new and the now, and with a perma-finger totally on the pulse of the zeitgeist, was heavily into Chicago house music. He’d heard and loved Joe Smooth’s Promised Land and recorded a faithful reworking of it before even Joe Smooth’s original had a UK release date (eventually releasing it on the same day). A song of unity and hope, it’s no different in sentiment to, say, Walls Come Tumbling Down, but whereas that was a Hammond heavy gatecrashing crie de guerre, Promised Land rode the crest of an E-kissed rolling and tumbling 808 wave. Blind loyalty pushed it to number 27 in the charts, but beyond that it failed to grasp the imagination. Hindsight of course has shown it to be a terrific mark in time.

Style Council – Promised Land

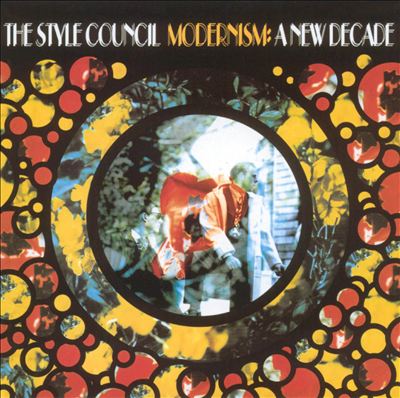

It was almost inevitable that when the Style Council presented Modernism: A New Decade to Polydor, the label would baulk at its hit-free content. There was no angry and spitting politico Weller, no Euro-continental jazz to soften the edges, none of the classic songwriting they’d come to expect from their talented young charge (Weller being just 30 at this point). Modernism: A New Decade was a pure house album, filtered through English notions and sensibilities, but a pure house album all the same. It favoured programmed rhythms and sequenced electro basslines over, y’know, actual bass and drums. It flung the guitars away and replaced them with weaving and shimmering synth lines. It was long and meandering with chants and shouts in place of a more traditional approach. Toundly rejected by Polydor, it would remain in the vaults for 20 years, only seeing the light of day when the all-encompassing, warts ‘n all Style Council Box Set was released at the end of the millennium.

And yet…

Modernism: A New Decade has its moments. Hindsight will show that its creator was frustratingly ahead of his time, that eventually Joe Public could and would groove to machine-driven, guitar-free music. Hindsight will show too that he really meant it, maaan. Just as he’d tackled the spiky Funeral Pyre with bile and aggression beforehand, and just as he’d go on to knock seven shades of shit from his guitar on Peacock Suit, Weller approached Modernism with nothing less than 100% of his cock-sure conviction.

Love Of The World‘s morse code intro and gospelish diva on backing duties…Sure Is Sure with its Italo house piano and Rotary Connection stacked vocals…a nascent That Spiritual Feeling, a track Weller would re-record as a solo artist – and a track that still finds a place in his live set to this day, usually as a refrain to the whacked-out and slightly psychedelic version of Into Tomorrow that normally closes his set, the proof – if it were needed – that its writer holds the material in high regard and that we, the listener, just need more time to appreciate it all.

The World Must Come Together is the perfect example.

Style Council – The World Must Come Together

Its message of unity and hope could’ve been written specifically for the times we currently live in, and Weller’s high and soulful vocal goes a long way to conveying its idea. Channelling his inner Marvin Gaye, he chants the title in the chorus, slipping into falsetto in the verses. Synthesised strings sweep across its clattering and steam-powered rhythm. Electro hand claps punctuate the end of lines. Sampled spoken word pops up in the gaps. A jangling Roy Ayers-ish vibraphone provides the break, but we’re soon back to the titular refrain, a parping, recurring hookline coming and going as the textured cadence of the beat rolls ever forward. It’s a bit of a slow burner, but I’d suggest that, if this were to appear as a new track on a Weller solo album next week, it would be roundly applauded.