A week before my 16th birthday, with freshly-minted National Insurance card in my hand, I went into the local supermarket with my pal and left half an hour and one unexpected interview later – “Q. With what method should you lift a heavy box? A. “The mechanical method, of course.” – with my first job. 4 hours on a Saturday morning and a further 3 on a Monday night would give me enough disposable income to buy a record and pay for a pint if I was lucky enough to be served, with enough left over to allow me to save a fiver for a rainy day. I can barely save a fiver nowadays, but back then the world was my oyster and the possibilities were endless.

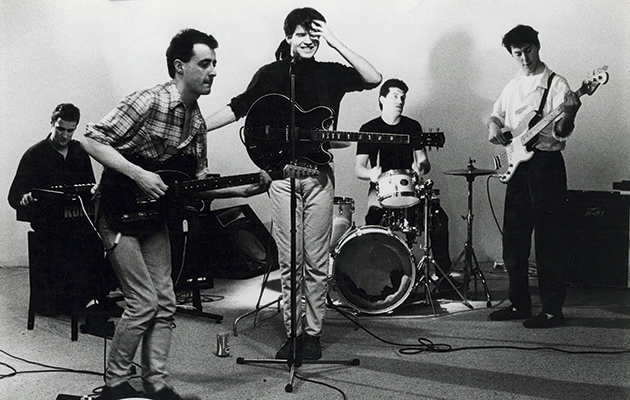

That job paid for some of the best records in my collection. Once I’d discovered The Smiths, I’d buy a different 12″ each week until I’d caught up with their latest release. Likewise with New Order. The only other person I knew who liked The Smiths was Steven Cairney, so when he mentioned them in the same sentence as Echo & The Bunnymen and Lloyd Cole & The Commotions, those bands were next on my hitlist. A record collection that was thus far populated by the most generic of records – every evenly-numbered ‘Now‘ album for example, but only up until Now 8 (my gran bought me a Now album every Christmas and died after Now 8), a smattering of Adam & the Ants and Madness albums and a couple of Greatest Hits collections from Blondie and Queen – began to take shape, growing in direct corelation to the quiff on my head, previously cultivated in tribute to Love And Money’s James Grant but handily becoming more Morrissey-esque with each subsequent Smiths’ record.

To an extent mirroring what would become my current working environment as the token male teacher in a primary school, I worked as the only ‘man’ alongside a gaggle of slightly older girls, all friends who went to a different school from me. They were all at least a year above me. One or two had actually left school, and were students in Glasgow. When you’re 16, 18 year old girls seem incredibly exotic and so far out of reach. These girls weren’t actually that exotic – they were mostly from the Ayrshire backwaters (which, to some, makes them incredibly exotic) but they were definitely out of reach. All had boyfriends and chittered and chattered about them for every long hour of their shift. One or two of the boyfriends had cars and one, Tony, (I may have changed his name) had a motorbike. They always asked me about my hair, which I knew was a constant source of amusement for them. “Is it sticking up when you wake up in the morning?…….How d’you keep it up?” they’d ask in barely disguised metaphors. “With Brylcreem,” I’d reply obliviously. Giggle Giggle, gaggle gaggle, chitter, chatter, chitter, chatter, hee-hee-hee! For four hours every Saturday and three on a Monday after school.

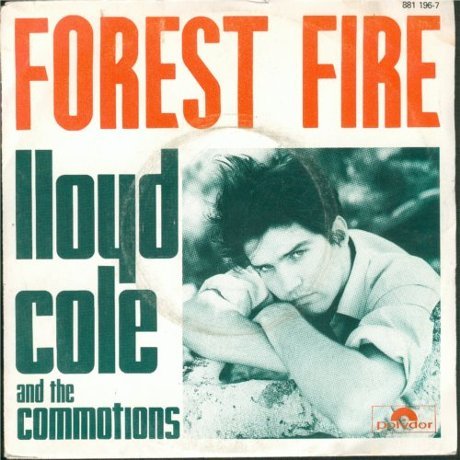

On one shift, over the click-click-click of an old hand-held pricing gun, one of the girls got chatting to me about music. “D’you like Lloyd Cole?” she enquired. I’d only just bought Rattlesnakes on the back of Steven Cairney’s mentioning of them, so I talked a wee bit about it. In truth, I loved Rattlesnakes, I still do, but I wasn’t going in feet-first with that admission. “D’you like the song ‘Forest Fire’?” she asked. It was my favourite track on the album. “D’you know what Tony wrote to me? He left a note in my bag that said ‘We’re a forest fire, every time we get together.’ Isn’t that the most romantic thing you’ve ever heard?” It was just about the most adult thing I’d ever heard at that point in my life, that was for sure, and I can never hear Forest Fire without the flashback memory, me in my over-sized company work jacket, cuffs turned up out of necessity rather than in tribute to Don Johnson, she in her work-provided gingham dress and grown-up outlook on life. Flash bastard Tony, with his motorbike and his brilliant-looking desert boots and his collapsed-quiff fringe and his just-left-school boy about town swagger has forever killed it for me.

Lloyd Cole & The Commotions – Forest Fire

It’s a great track though, and probably the first I heard where I realised a guitar solo didn’t have to mean a lightning-fast blur of fingers on the 24th fret of a jaggy-shaped hideous guitar. Johnny Marr didn’t go in for guitar solos at all and was the very antithesis of what a guitar hero was supposed to be. Will Sergeant peppered Echo & The Bunnymen’s finer moments with effect pedal-heavy shimmer, something I was unable to replicate on the cheap plank of wood I had the cheek to call a guitar. But on Forest Fire, Neil Clark’s slow-burning twang fits the mood perfectly, closing side 1 of the album with a brilliant repetitive refrain. It’s a guitar solo you can sing. It’s even a guitar solo I can play. It was, for many a year, the only solo I ever needed. Even if it’s been ruined by Tony forever.