A few months ago I posted about the burst of classical music that The Smiths used to signify they were taking the stage. Walk-on music, when used as effectively as The Smiths did it, is an integral part of the live experience. Those in front of the stage have their senses heightened…quicksilver adrenaline courses through the collective mass… eagerness is fit to burst and, as one, they peak when their heroes take the stage. In the article linked above, Mike Joyce talks about the prickling of the hairs on his arms as Sergei Prokofiev’s music reaches its climax and the group emerge from the shadows and onto the stage. Intro music is pure theatre and high drama, powerful in its effect for audience and band alike.

The recent death of Mani had me revisiting the Stone Roses catalogue and reminiscing about the Stone Roses gigs I’d been at. I say gigs, but Stone Roses shows were more of an event than a mere gig. The minute the group began to pick up traction, they eschewed the usual circuit of venues and instead put on ambitious landmark concerts.

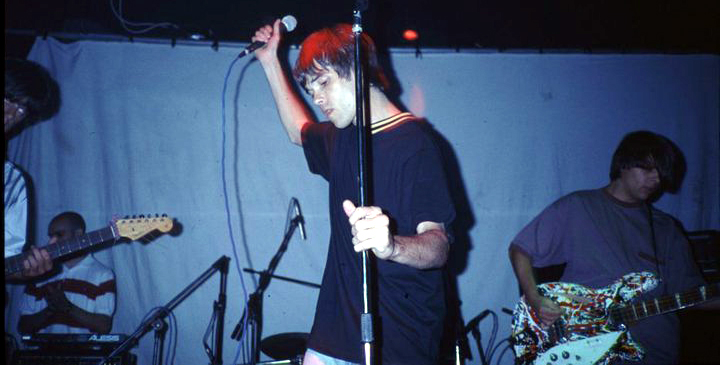

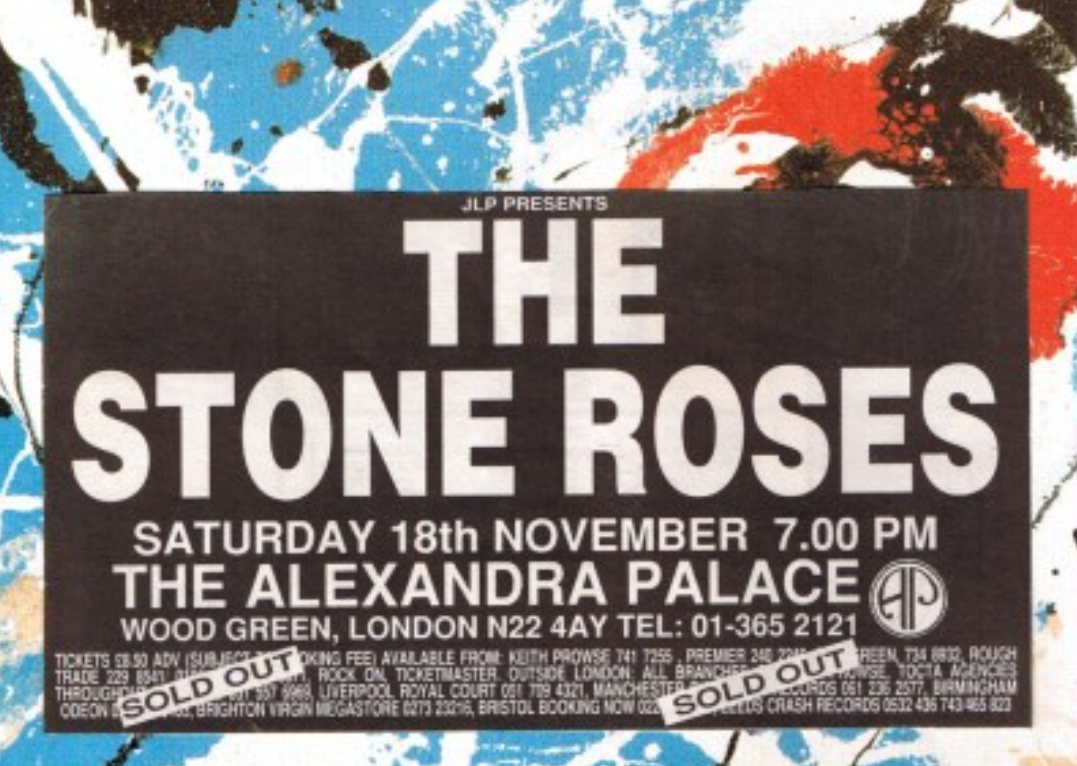

In the space of five rapid months in 1989, Stone Roses went from Glasgow Rooftops (above) – part of the touring circuit for bands of a certain size – to the Blackpool Tower Ballroom to a November show for 7000 rockers and ravers in London’s Alexandra Palace, at the time known as the broadcasting birthplace of the BBC and scene of some of those trippy 24-hour Pink Floyd and Soft Machine ‘happenings’ of the late ’60s, but certainly not the usual venue any bands might think to try and fill. Nowadays of course, any two-bit act with a bit of a following can add a date or two in the airy north London glasshouse, but in 1989 the Stone Roses’ choice of venue was genuinely inspired.

Fast forward another six months and the group would set up stall on Spike Island, a windswept and chemically-polluted estuary of the Mersey. Two months later they’d play their final show (for then, anyway) in a huge tent on Glasgow Green, 10,000 rockers, ravers and by now bucket-hatted bampots witnessing the band at the peak of their powers. The travelling tent idea is also now fairly standard practice for bands of a certain size these days. (Spike Island less so.)

As the band’s popularity grew, they went from the standard idea of support act plus half an hour of playlisted music to an actual rave culture-inspired show, the group just one element of a spectacle that would involve guest DJs dropping crashing house beats and hip hop on the P.A., lasers and strobes on the lighting rig, mass E communion in the audience and generally good vibes all round. These shows were a million miles from watching Gaye Bykers On Acid from a cider-soaked corner of Glasgow Tech or the Wedding Present at the QMU or any other touring guitar band of the era you care to mention. Yes, even you, Primal Scream. In 1989, Bobby was still looking for the key that would start up their particular bandwagon. (It was somewhere down the back of his Guns ‘n Roses leather trousers, I’m led to believe.)

All of those shows mentioned above (I was at three of them) began with I Wanna Be Adored. Since writing the song, or at least since the release of that debut album, has there ever been a Stone Roses show that didn’t start with it? I don’t think so. I Wanna Be Adored is, in its own way, a senses-heightener, a quicksilver surge of electricity, an early peak in a set full of peaks, but in the live arena, it too would come rumbling from out of the corners, fading in as an intro tape heralded the group’s imminent arrival.

Stone Roses intro music:

I’ve spent 35 years convinced that this music was made by the Stone Roses themselves, an abstract piece of art thrown away in the same vein as those backwards experiments they put onto b-sides, played for fun, recorded then used sparingly but appropriately. Certainly, the thunking, woody bassline is pure Mani. The hip-hop beat pure Reni. The sirens a clear extension of John Squire’s clarion call at the start of Elephant Stone.

Hearing this from Ally Pally’s carpeted floor minutes after Sympathy For The Devil is still strong in the memory. Hearing it again in the sweat-raining big top on Glasgow Green, many there unaware that this was not mere incidental rave music but Stone Roses’ call to arms (but we knew, oh yes, we knew, and excitement was immediately at fever pitch) still provokes a conditioned response in 2025.

It wasn’t made by Stone Roses though. Turns out it’s a piece of obscure-ish hip hop from 1987, looped, tweaked and added to by the Stone Roses team. The original – Small Time Hustler by The Dismasters – is immediately recognisable from that Stone Roses intro. Really, all the Stone Roses did was stick a few sirens on top of it…but combine that with Ally Pally’s echoing rave whistles and Glasgow Green’s surge of euphoria and it makes for high drama.

I wonder how many folk knew – truly knew – the source of that Stone Roses intro tape back in 1989?