I was out the back door a few nights ago. We’d given the shrubbery a festive, twinkly make-over and the remote control to turn the lights off had stopped working from the lazy comfort of inside the house, meaning I had to move closer to them and, y’know, actually go outside to turn them off…half cut…at 2am…wearing pink Crocs (not mine). As I moved closer to the lights, a sudden and loud flapping noise – total Attenborough nature documentary in sound – broke the still Ayrshire silence. I froze. Almost immediately, from the big tree behind my fence, an owl began hooting.

How great!

We’re not country dwellers by any means, the Glasgow train line runs behind us, down the hill behind that big tree, but we’re right on the fringes of the town where it meets its ever-shrinking green belt and we’re clearly close enough for unexpected wildlife. It’s not been back since, but I’ll be listening out for that owl any time I happen to be awake in the small hours. Or wee hours, given how regularly I make the broken sleep stagger to the bathroom these nights.

The one owl I can I hear any time I like is this – the most interesting, most unique and unarguably the greatest track that’s graced these ears this past year.

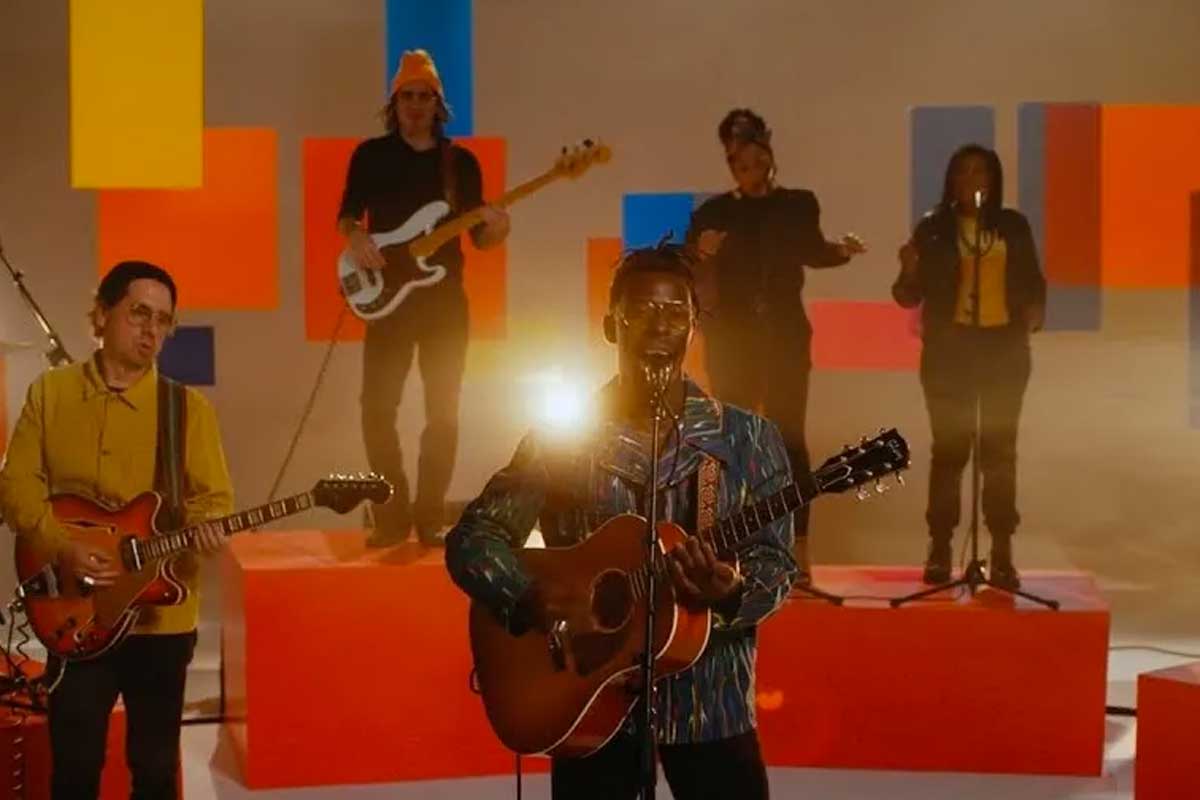

The Tenementals – The Owl of Minerva:

Early in the 19th century, the German philosopher G.W.F. Hegel wrote that “The owl of Minerva spreads its wings only with the falling of dusk.” It’s a line that suggests that true historical understanding only comes with hindsight – a phrase that could very much apply to Glasgow’s foundations in slavery and clashing religious intolerance; a reawakened city, perhaps, but one that’s still in conflict with itself.

Both inspirational and educational, The Owl of Minerva is delivered in a rich, actorly, Glaswegian brogue atop a clatter of guitars, like an electric shocked Public Service Broadcasting riding on the sort of sludgy, serrated, repetitive riff that Iggy Pop might be inclined to drop his trousers for. A fly-past of Glasgow’s streets and their history, it’s terrific. And immediate. And supremely poetic.

Mungo’s children lie in slumber, in ballrooms of pleasure and Bars of L, silent forges of production… The cantilevered roost of the Finnieston Cran(e)… Red Road in ruin… Broken bricks of Utopia… Carnivals in Castlemilk conjuring a constellation… Hills of Hag… The rapids of revolution… The highway of historical time… Beyond the Black Hills… Proddy John… Commie John… Bible John… Poppers John… Bengal/Donegal… Gorbals teens/Glasgow Greens… New futures/New presents/New pasts… And still the river flows.

This is not the soft focused, rain-soaked Glasgow of the Blue Nile. Nor is it Simple Minds’ idea of the Clyde’s majestic past writ large in Waterfront‘s filling-loosening bassline. Nor is it Alex Harvey’s sense of menace and theatre. Or Hue and Cry’s shoulder padded and reverential Mother Glasgow. It’s all of this and more, a Glasgow song that’s scuffed at the knees yet literate and informative and vital for the 21st century. And it’s seemingly arrived straight outta the blue, an unexpected blazing comet for our times.

The Tenementals crept onto my social media feeds at some point late October/early November and the by the time I’d wandered off piste and hauf pissed to properly check them out, I had, typically, missed their Oran Mor album launch show by one night – a free entry gig too, where you had the chance to buy the album and it’s thrilling lead track.

If they don’t look like yr average group of skinny jeaned, facially haired, too cool for school gang of guitar stranglers, that’s because The Tenementals aren’t really any of this. Lead vocalist David Archibald is Professor of Political Cinema at Glasgow University. They’ve collaborated with Union man and political agitator Mick Lynch. Their record label is called Strength In Numbers. Socialists to the core, their self-given job is to enlighten their listeners to the plight of the suffragettes, the beauty of La Pasionaria and the warped, cruel and beautiful history that forged the place from where they sprung.

The rest of the album is equally as thrilling, by the way. See them become more prominent in 2025.