I’m a sucker for a music biography (heck, I’ve written at least one) and so found myself at the Mike Joyce book event in Glasgow last week. The most bizarre thing happened before it had even started.

A couple of guys came in and sat in the empty seats beside me. With nothing happening on the stage as yet, they did as we all do – they took out their phones and began scrolling through social media. Five minutes later, the guy next to me started Googling ‘Mike Joyce’ (I wasn’t really being nosy; being of a certain vintage, the text on his screen was massive – there’s a guy who sits about three rows in front of me at the football and half the crowd can read the texts his wife sends at full-time too – it’s clearly a common thing if you fall within a certain demographic.)

Very soon my neighbour alighted on the interview I did with Mike eight or so years ago, where I asked him to chat about his favourite Smiths tracks. I watched side-eye as the stranger beside me read the lot, desperate to say something to him, but too timid to acknowledge it. I then did as any self-respecting ‘like’-hungry social media user would do, and stealthily updated my Facebook status with my phone held very close to my still-thumping chest as I typed. Weird and strange, but pretty cool.

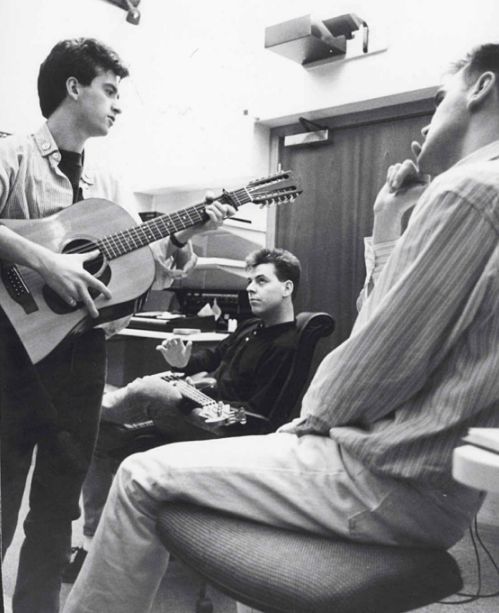

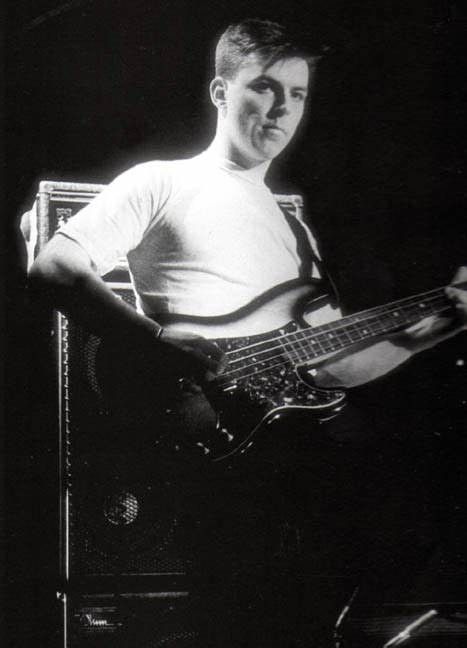

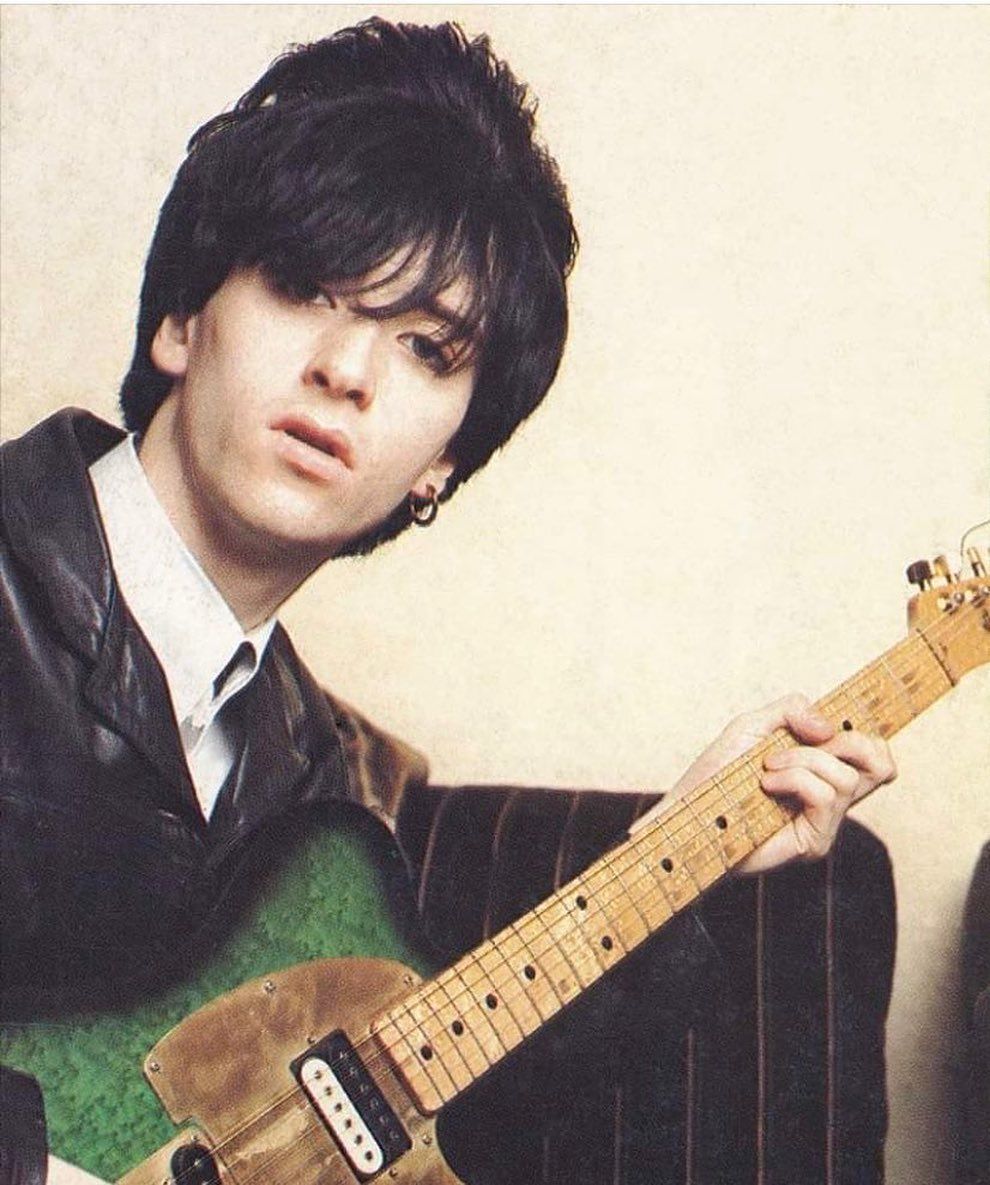

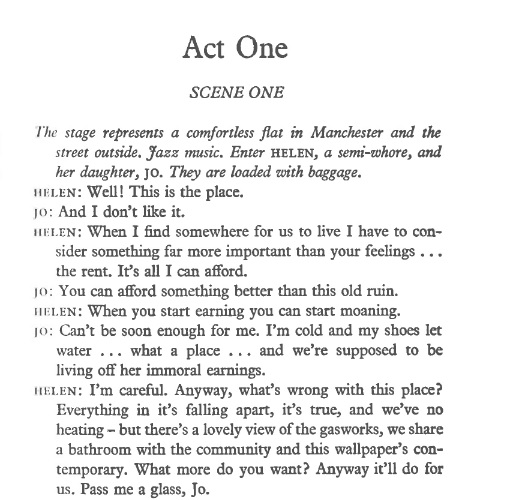

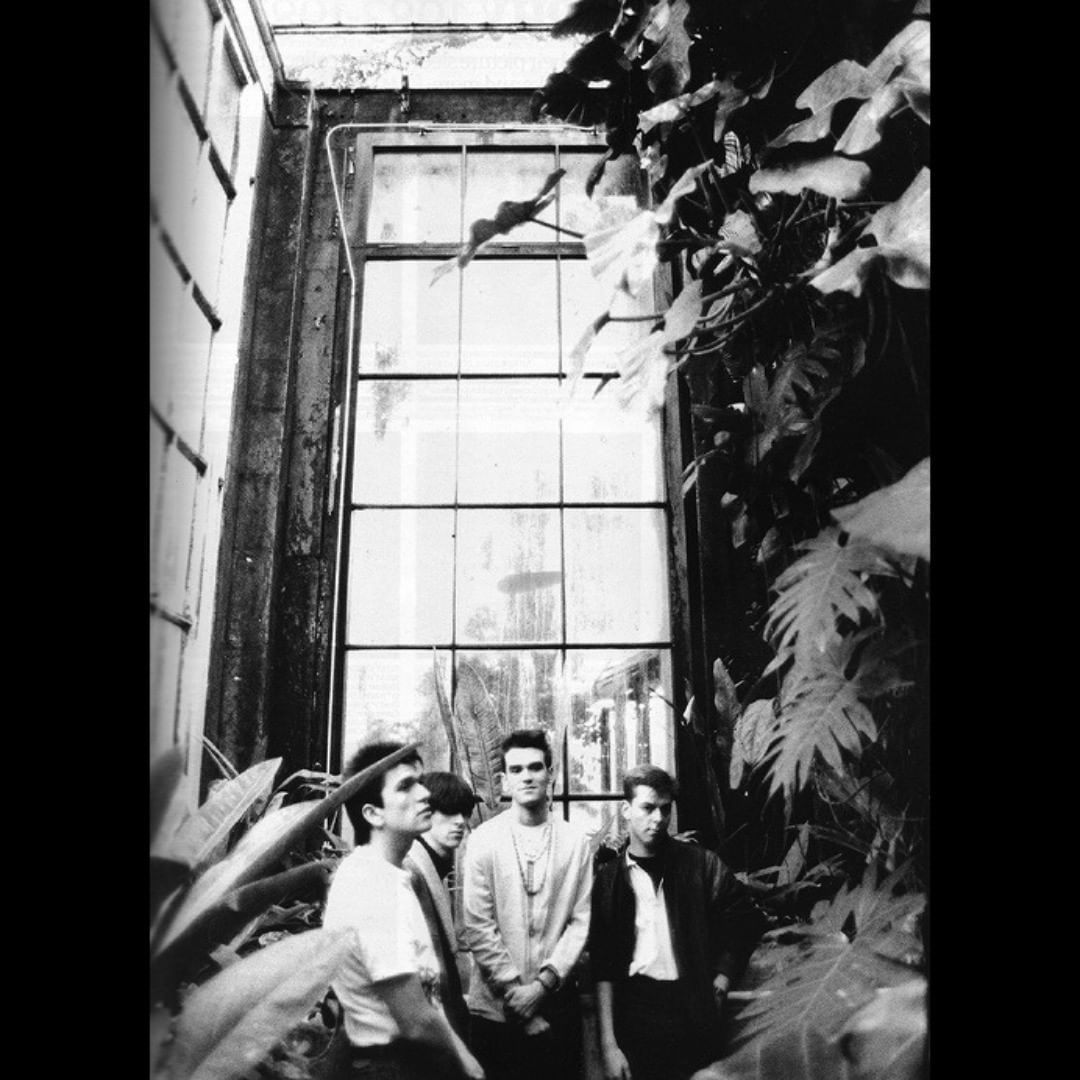

Held in the Glee Club, the event was, as it turned out, the perfect fit for a venue more in tune with comedy events than music or literature. Interviewed onstage by Scottish radio legend Billy Sloan, Mike Joyce was funny, engaging and extremely lucid, singing drum parts and guitar riffs and offering up tasty morsels of Smithsian trivia – direct despatches from a constituent part who’d fought the good fight from those unique and idiosyncratic trenches.

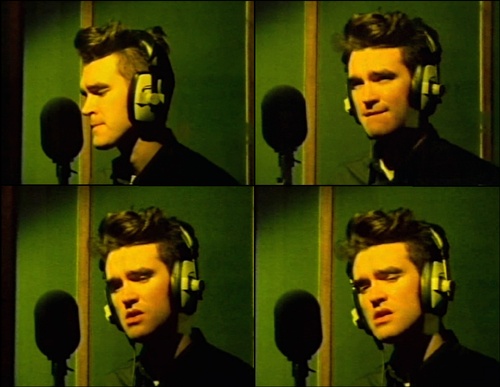

With a mixture of significant and less consequential events from the pop landscape of 40 and more years ago pouring rapidly and freely from the affable drummer, many being told for the first time, he offered a unique insight into the deft workings of the Morrissey and Marr song-machine. Over two halves of a night, he had a quietly rapt audience, and even when the questions from the floor at the end turned serious – he weeps softly when talking about Andy Rourke – and then tediously obvious – ‘Will The Smiths ever reform?‘ (puh-lease?) – he answered them all with gracious dignity and a sense of humour that stopped it all getting a bit silly.

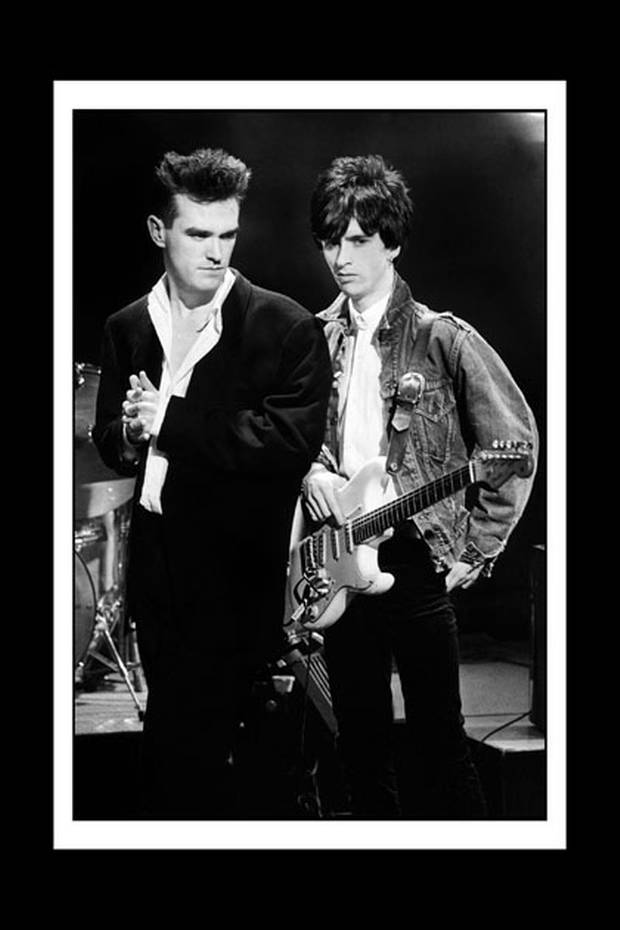

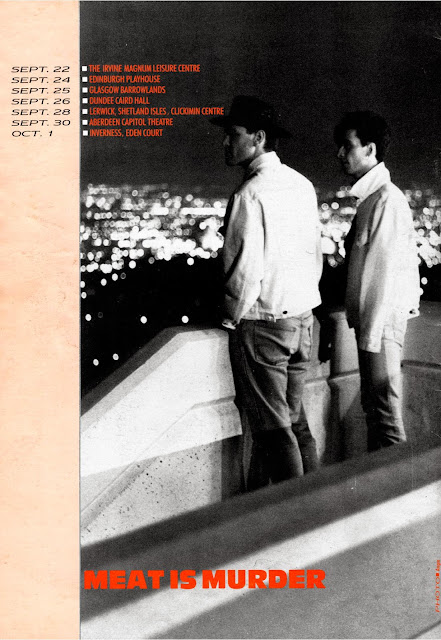

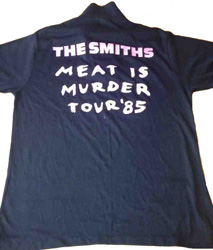

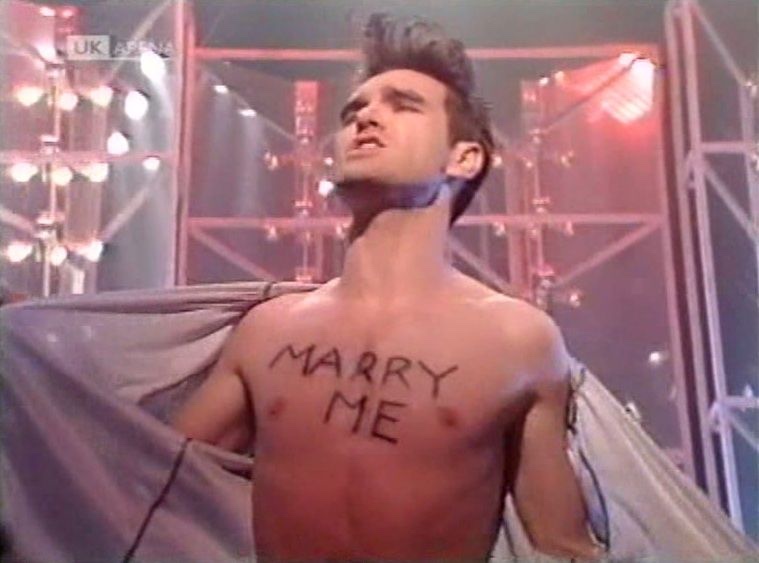

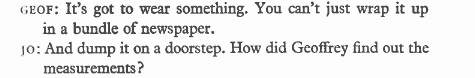

Mike, as it turns out, is the biggest Smiths fan of them all. ‘What’s it like selling out the Albert Hall?’ he asks himself in the intro to his story. ‘It’s unfathomable’, he answers simply. He can’t quite believe the things that happened to him, from hearing the first mind-blowing Smiths recordings, to playing Top of the Pops, to having Mick Jagger dancing side-stage in New York, he and Johnny mid-song and gape-mouthed at the ridiculousness of it all. Mike’s Smiths years were a blur of ‘pinch me’ moments that, even nowadays, he can scarcely fathom. He spent little more than half a decade in The Smiths, yet Mike’s entire life since has been defined by those years. And now, it seems, is the time to tell his story.

Joyce, as you may know, divides opinion in the Smiths community. On the one hand, he’s a quarter of one of our most individual and exciting groups. On the other, he’s the bandmate who refused to settle for ten percent, the traitor who took the group’s principal members to court for a greater share of what he felt he was owed. It’s all a bit murky and eugh, really.

But yet, while he briefly/bravely refers to this, Mike prefers instead to focus on what made The Smiths so great; the ridiculously high watermark of consistent quality across their catalogue, the riotous gigs, the in-band humour and the tight-knit ‘us v them’ stance that got them through it all. The Drums, he says, should be approached as a celebration of the times rather than a warts ‘n all story. It is. I’m halfway through and it’s a very easy and rapid read. I think you’d like it.

To bookend the show, something else happens.

At the show’s mid-point, Billy Sloan had spotted me from the side of the stage and had come over. ‘Don’t leave at the end,’ he implored. ‘Wait here.’ (I know Billy a wee bit, it’s not as if he has a habit of picking random strangers out of a healthy crowd). At the end, he’s back over. ‘Did you buy a book? D’you want it signed? You’re not waiting in that queue – look at the length of it…‘ and he points to a couple of hundred folk snaking their way up the side of the venue and up to the mezzanine where the signing table is set up. ‘Follow me. Quick!‘

We’re backstage, Billy fussing over my bag. ‘Get your book ready, take the record out of its sleeve, d’you have a pen?‘ And then… a classic Sloanism. ‘Mike! This is my good personal friend, Craig, He’s a great writer and you should meet him.’ And Mike Joyce is there. He’s easy to chat to, but all the things you might want to say, he’s heard them all a thousand times. I don’t even think to mention I’d interviewed him in the past (and I actually think that interview played a small part in this book being birthed.) Instead, I play it cool.

“Thanks for the music, Mike. It’ll play forever.”

“I know it will,” he winks.

He signs my book, he signs my 7″ of Hand In Glove, drawing a wee snare drum above the place where Johnny signed it a decade ago and we chat, of all things, about how shite it is to lose musical allies and friends to cruel and unforgiving illnesses.

Not yr average Wednesday night.

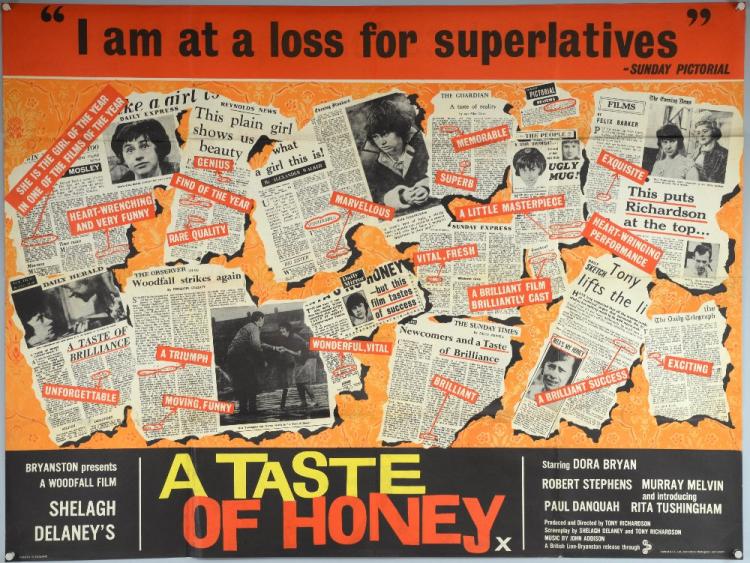

The Smiths – This Night Has Opened My Eyes (demo)

Mike Joyce ‘The Drums‘ is published by New Modern and is out now.