Stevie Wonder’s trajectory is quite the thing. From Little Stevie Wonder to Motown hit machine, synth pioneer and auteur of funk to socio-political commentator, God-fearing introspective soulster and syrupy ’80s balladeering duetter to his undisputed status as one of the greats, his vast (and decidedly patchy) back catalogue has the lot.

Patchy it may be, but his run of albums in the early ’70s, from ’72’s Music Of My Mind to ’76’s Songs In the Key Of Life is a collection of hard-hitting, hit-packed and ideas-filled records matched only by David Bowie’s outpouring in the same spell. We tend not to say these sort of things while the artist is still with us but wait for the clamour when Stevie passes and that incredible run – five albums in four years – will be quickly elevated to Essential Album status.

What’s all the more amazing is that during this time, Stevie was writing not only for himself but for others too. He threw Superstition in Jeff Beck’s direction before immediately realising the error of his ways and (much to Beck’s annoyance) reclaiming it for himself. He produced an album for his ex wife, Syreeta Wright, worth seeking out if only for ‘Cause We’ve Ended As Lovers; heartbreak laid bare on record (and a track that Jeff Beck would go on to reinterpret to devastating effect).

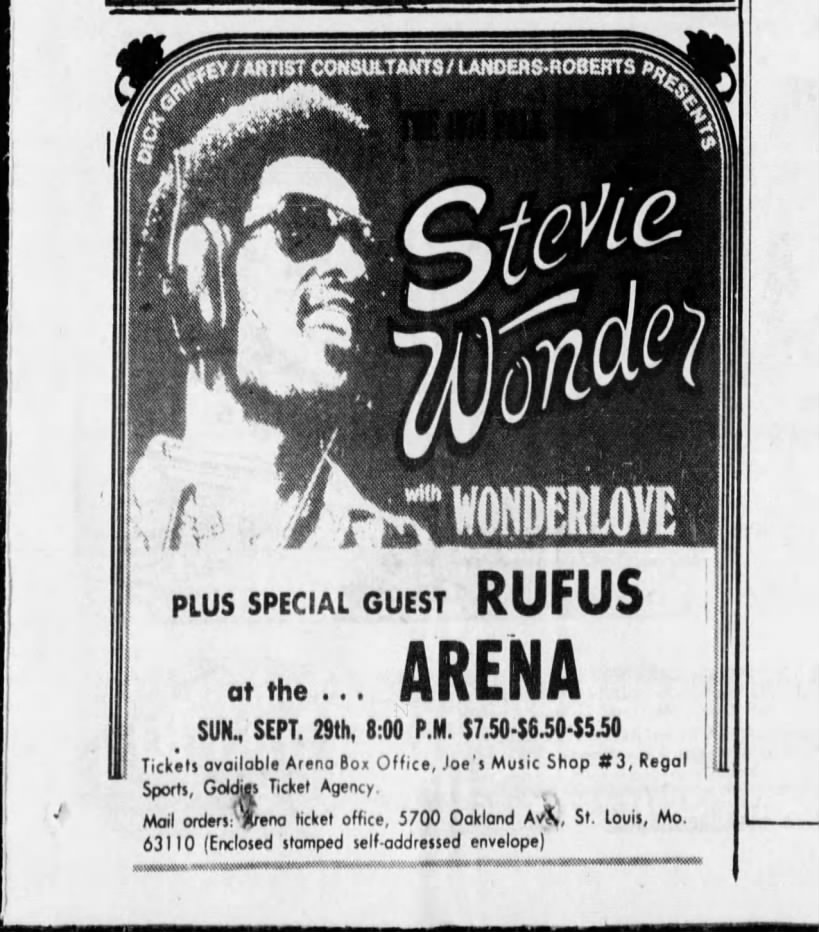

And he wrote Tell Me Something Good for Rufus.

Have a watch at this smokin’ hot live version, from American TV.

Despite Wonder being nowhere near the record, it still bears all the hallmarks of prime time Stevie; whipsmart wakka-wakka clavinet, inventive and tuneful drumming, space between the notes for the funk to brew and on top of it all, a singer who packs a proper soulful punch.

The clip above is outrageously brilliant. For one, it’s played totally live and in the moment; no overdubs, no lip synching, not a bum note in earshot. Chaka Khan sits in the pocket, metaphorically and visually, occupying the space between the guitar players, a pocket dynamo in era-defining flared jeans, her sparkly top shooting laser beams of studio light straight outta the TV screen and into young and immediately hypnotised American minds. But don’t let the clothes and the hair and the looks detract from the fact that she tackles the vocal with everything she has; gritty and low, octave-jumping, quiet and sultry, skyscrapingly dramatic – the whole gamut of soul, in other words.

The players flanking either side of her swagger with a pure coked-up arrogance. The wild-eyed guy on voicebox is playing dripping wet funk on a Fender Musicman – Fender’s budget-friendly, entry-level electric guitar, his high-waisted trousers meeting the point where his shirt begins to button. The bass player, all bicep and lip curl and eye-catching crucifix (S’OK, mom and pop, I’ll have her back before midnight y’all) plays with pure instinctive feel. He knows he’s good too. The self-assured heavy breathing in the pre-chorus is, seemingly, right up his particular street. The bass face he pulls and those little self-satisfied gurns he does when he drops in a particularly funky line completes the look. His hands barely move, yet the groove thuds out in simpatico with the tight but loose drummer in dungarees. Either side of the drummer, the keys players drive it forward, clavinet morse-coding the melody, Fender Rhodes holding down the tune. And on top of it all, Chaka, delivering the sort of blistering vocal performance you’ve maybe only heard up until now on a Family Stone track, or perhaps that PP Arnold TV performance where she duets with Steve Marriott on that great ’68 performance of Tin Soldier. Seek it out…

So, yeah, it’s a great performance of a great song. A few months beyond this, Rufus would become Rufus and Chaka Khan, testimony, should it be needed, that the vocalist was perhaps the strongest piece of an extraordinarily soulful and funky jigsaw.