Hey! You! Put aside the dog-eared copy of Absolute Beginners that you’re currently re-reading for the 5th (6th?) time. Lift the needle from the freely-spinning Cafe Bleu on the old Dansette. Brew yourself a fresh cappuccino, or even an espresso forte, and sit back and read this.

Jazz is America’s first music, a liberation from daily struggle, the artist given the freedom to play and sing however they choose. Those jazz cats used the music as a platform for cultural expression, whether that be Billie Holiday’s heart-stopping vocal on Strange Fruit or John Coltrane’s faith meditation on A Love Supreme, Miles Davis’s exotic inroads on the voodoo funk of Miles In The Sky or Louis Armstrong’s rasping love song to the Wonderful World he found himself living in. Oppression, worship, love, death…jazz is life itself. Folk that say they don’t like jazz just haven’t yet found the strand of the genre that will resonate with them.

Jazz, though? Soul – that’s obvious. Blues? That’s obvious too. But jazz? Why jazz?

Way back a hundred or so years ago, ‘jazz’ was a slang word used to describe liveliness and spirited behaviour; ‘She’s so jazz!’, ‘This dance is wildly jazz!’, ‘That baseball team is totally jazz!’ etc. So, in the time it took Louis Armstrong to parp out a trumpet triad, ‘this music is totally jazz!’ went from adjective to noun. Interestingly (or otherwise) the word ‘jazz’ itself originated from the word ‘jism’, in that if you were lively and spirited between the sheets with the person of your fancy, well…you know what tends to happen. So, the next time you hear the word ‘jazz’, ponder on that for a bit.

“Hey boy, bring me ma drink,” Hey boy, play me anutha toon,” “Hey boy, don’cha quit playin’ until you been told to quit playin’.” In the jazz clubs during the good old days of white supremacy and inherent, unfiltered racism (which could be either last century or last week), American black men took to calling one another ‘man’ – a required and regular reminder of respect between the oppressed that their fellow brother should be just as valid and just as valued as any other man in the place.

“Hey, man. You doin’ okay?”

Nowadays, folk like myself use the word without thinking of its true origins. It’s worth reflecting the next time you drop the word into conversation.

Those black me and women could trace their collective blood line back to slavery. Of the many thousands of Africans who were shipped to the Americas, the ethnicity of a large percentage of the people was rooted in the Wolof tribe. As with all indigenous people, the Wolofs kept their history alive through song, passing down stories and traditions from the elders through music and oral storytelling. Hence the phrase ‘folk music’.

The Wolof word for ‘music’ is ‘katt’, and it’s thought this is the origin of the phrase ‘jazz cat’.

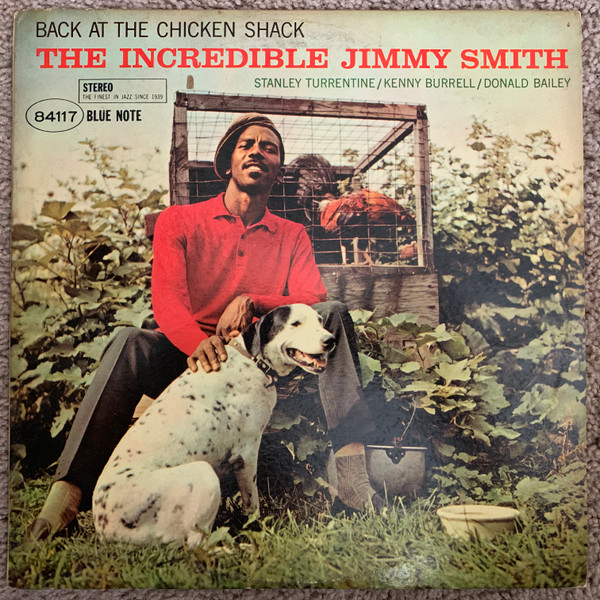

Me, I’m a fair weather jazz fan. My list of favourite jazz albums would look as obvious and lightweight as one you might find published in the arts section of the Guardian or in the near-the-back pages of Mojo. Miles…Coltrane…Nina… bore off, pretentious jazz wanker. With the sun blazing a hole in the sky and the last week of the summer holiday slowly fizzling to a close, it’s Jimmy Smith‘s Back At The Chicken Shack that’s been doing it for me these past few days.

Here’s something to ponder – why is it that the soul and blues players kept their Sunday name – James Brown, James Carr, but the jazz cats adopted the more street variation – Jimmy McGriff, Jimmy Smith?

Anyway. Jimmy Smith. He’s the link between jazz and soul, his shimmering and colossal Hammond organ sound driving his group with a grit and right-on funkiness that’s impossible to dislike. Like all the best jazzers, his group was fluid and ever changing, evolving its sound as each musician passed through on their way to wherever it was they were going.

Jimmy Smith – Back At The Chicken Shack

On Back At The Chicken Shack‘s title track, Smith trades call and response organ phrases with the omnipresent Kenny Burrell on guitar and the ubiquitous Stanley Turrentine on tenor sax, his regular drummer Donald ‘Duck’ Bailey keeping the beat just on the right side of slow but progressive.

Burrell is all over the Blue Note catalogue, both as band leader and sideman, and his Gibson 400 CES ripples patterns of woody eloquence at every opportunity. On Back At The Chicken Shack he’s content to play understated augmented chords beneath Jimmy Smith’s expressive playing in the first and last sections, but in the middle, after his bandleader has given him the nod, he’s off and flying, fingers cleanly picking tight and taut melodies across the strings and frets with a speedy ease that’s both mesmerising (as a listener) and frustrating (as a hamfisted guitar player). His phrasing, the spaces he leaves between the notes, is perfect. Off-the-cuff-playing like this doesn’t come easy, as easy as it sounds.

Turrentine is no stranger to the Blue Note discography either and his forceful yet soothing sax playing swoops and soars in all the right places. The band falls in step behind him as he freeforms and riffs across the top of the steady groove being cooked up. If yr head ain’t nodding and yr foot ain’t tapping by this point, maybe you need to give your ears a wee clean out. Imagine hearing this live in a sweaty Village basement club, or even being spun by a hip DJ in the Flamingo in 1963, all the ace faces dancing in studied concentration. It’s enough to pop the buttons on yr tonic suit.

Back At The Chicken Shack – seek it out, man.