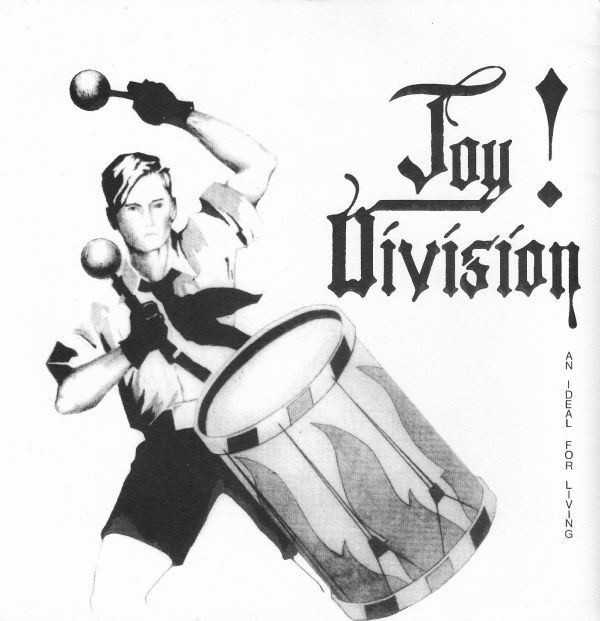

1978. At the time when Saturday Night Fever and Grease stubbornly refuse to budge from the top two positions on the album chart, just as the whole of Scotland is hypnotised by Archie Gemmell turning Dutch defences inside out down there in South America, right about the point when the ahead of the curve Swedes were banning aerosol sprays on account of their ozone-damaging properties (good luck being a Stockholm-based glue-sniffing, hair-dying punk rocker), Joy Division were releasing their An Ideal For Living EP.

If 1976 is punk’s Year Zero – and common consensus decrees it is – then the two-full-years into the future that is 1978 signifies the musical movement’s transition into post-punk. The unforgiving world of now! sound moves fast, and unless you’re one of those opportunistic phlegmy-trailed third rate, third wave cartoon punk bands who came along in the scabby wake of punk’s outgrown dead ends, the scene’s key movers and shakers were now very much in their imperial post-punk phase.

An Ideal For Living and its writers may have been a product of the punk scene, but see past the Hitler Youth drum-beating boy on the cover and the band’s name with it’s links to the very worst of contemporaneous modern history and you’ll conclude that, in attitude and outlook, Joy Division and their debut record was nothing less than post-punk.

It’s the breathing space that’s given to the instruments that does it.

Joy Division – No Love Lost

It’s low-budget, high concept, ambitious cinematic rock and then some. Just three instruments and a vocal line; linear, separated and identifiable, crystal clear and with all the fat trimmed off at the source. Peter Hook’s clang of bass and four string metronomic pulse, Kraftwerk by way of Salford, Bernard’s conservative use of slashing and scraping feral guitar, fed through an ear-bending phaser pedal for additional disorientation, the sheer dynamics of the drop ins and drop outs as the bass and drums dictate proceedings… this is all high drama travelogue played out by serious young men.

Where the worst of punk sounds like it’s recorded on sandpaper inside a cardboard box, the best of post-punk sounds futuristic and other-worldly.

It’s the drums on No Love Lost that separates it from the other guitar-driven records of the era.

Stephen Morris really wants his drums to sound like the expansive steam-powered hissing and spitting that gives Bowie’s Be My Wife such a coating of propulsive Victorian workhouse modernism, and although the group has yet to orbit Martin Hannett’s wild and idiosyncratic solar system, the production on No Love Lost hints at the very out there-ness they’d soon discover with Factory’s maverick desk controller. Morris’s drums are electronically treated; the snares refract and ricochet at the edges, the toms beat a heady and reverbed tribal thunk, the hi-hat sticks two fingers up to Sweden and sprays a tsk-tsk-tsk ton of ozone-damaging aerosol into the Tropsphere, the ride cymbal splashes a silvery sheen across the top of it all… it’s not a million miles away from Low-era Bowie at all.

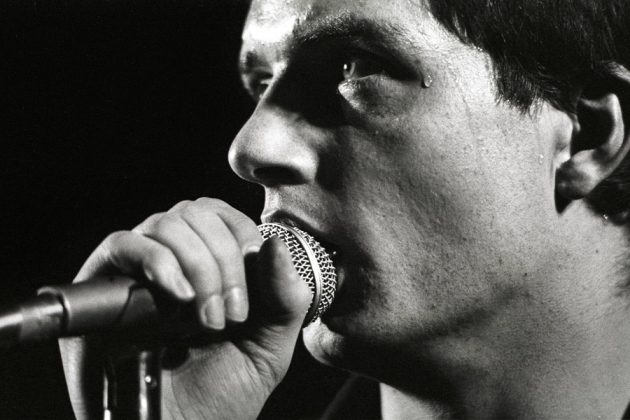

The vocals don’t appear until the three minute mark, a long intro – almost prog – by any fat-free group’s standards in 1978, and when they do arrive they’re both shouty and wordy. Ian Curtis flits between a mouthy punk rocker where the tune is less important than the attitude and the sort of arty and enigmatic spoken word delivery that you might find on a Velvet Underground record. As with the drums, the edges of his vocals are treated in echo and delay and all manner of mystery-enhancing effect-ect-ects. Did they ever better this? Of course they did…but as first releases go, No Love Lost is a real stall-setter.

Yeah. When Travolta was omni-present, when Gemmell was achieving God-like status, when Sweden was leading the way in planet-saving eco-friendliness, Joy Division was sowing the very serious seeds of post-punk. Essential stuff, I’m sure you’ll agree.