This is new. This is now. This is right up yr street.

Did your teacher ever stare blankly whenever you opened your mouth? This is The Wind-up Birds

Is it hard to get served at the bar? This is The Wind-up Birds

Do you get confused in heavy traffic? This is The Wind-up Birds

Do people invade your personal space every minute of the day? This is The Wind-up Birds

Any press release from a band called The Wind-up Birds that starts thus is going to grab your attention, right? The Wind-up Bird, as the cultured among us know, is a novel by Haruki Murakami; a time-shifting page turner that features lost cats, a man trapped down a well (that’s lost bloody cats for you), a flashback to the Japanese army and a man skinned alive. All the best bands have literate minds, of course, so The Wind-up Birds had me before I’d knowingly heard a single note.

Their penchant for well-written words is all over that press release, that’s for sure (although – sorry ’bout this – but these days I’m quite often the teacher who stares blankly at what comes out of some folks’ mouths. Not all the time, mind.) The band’s words continue in stellar, stall-setting fashion.

The Wind-up Birds are from Leeds.

The Wind-up Birds are not from Leeds (as in, United, Harvey Nics and Moyles).

The Wind-up Birds are from Leeds (as in, David Peace, Alan Bennett, Jake Thackray, The Wedding Present and Gang of Four).

They’re named after a book by Haruki Murakami. (Told you!) They write songs about car parks, and songs about pubs, and songs about work, and songs about escape.

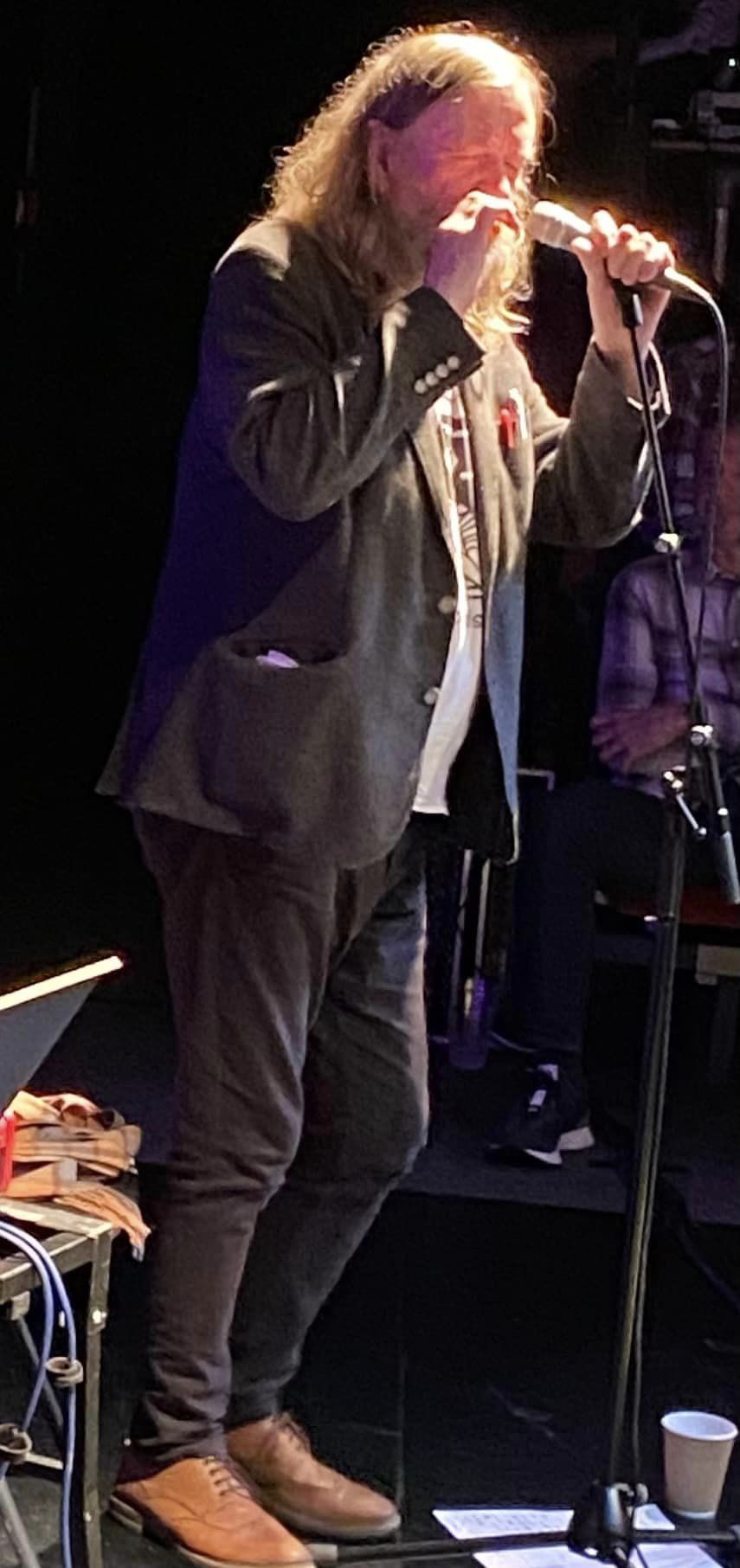

In an era where you wonder if you’ll ever again find a band with something to say, the kind of insight, perception and wit that The Wind-up Birds toss our way is almost embarrassing. Their song titles say it all: Ignore the Summer, Long Term Sick, That’s Us Told, There Will Be No Departures From This Stand, Families of the Disappeared, Slow Reader – like all great bands, The Wind-up Birds reflect and transcend the mundanities of the times they exist in. Vocalist/lyricist Paul Ackroyd has the scathing satirical bite of Mark E Smith, the warmth and pathos of Alan Bennett, the forensic observations of Jarvis Cocker, the kitchen-sink emotional clout of Morrissey; it’s all there, set to a cathartic post-punk racket that’s as unflinchingly messy and beautifully ugly as life itself.

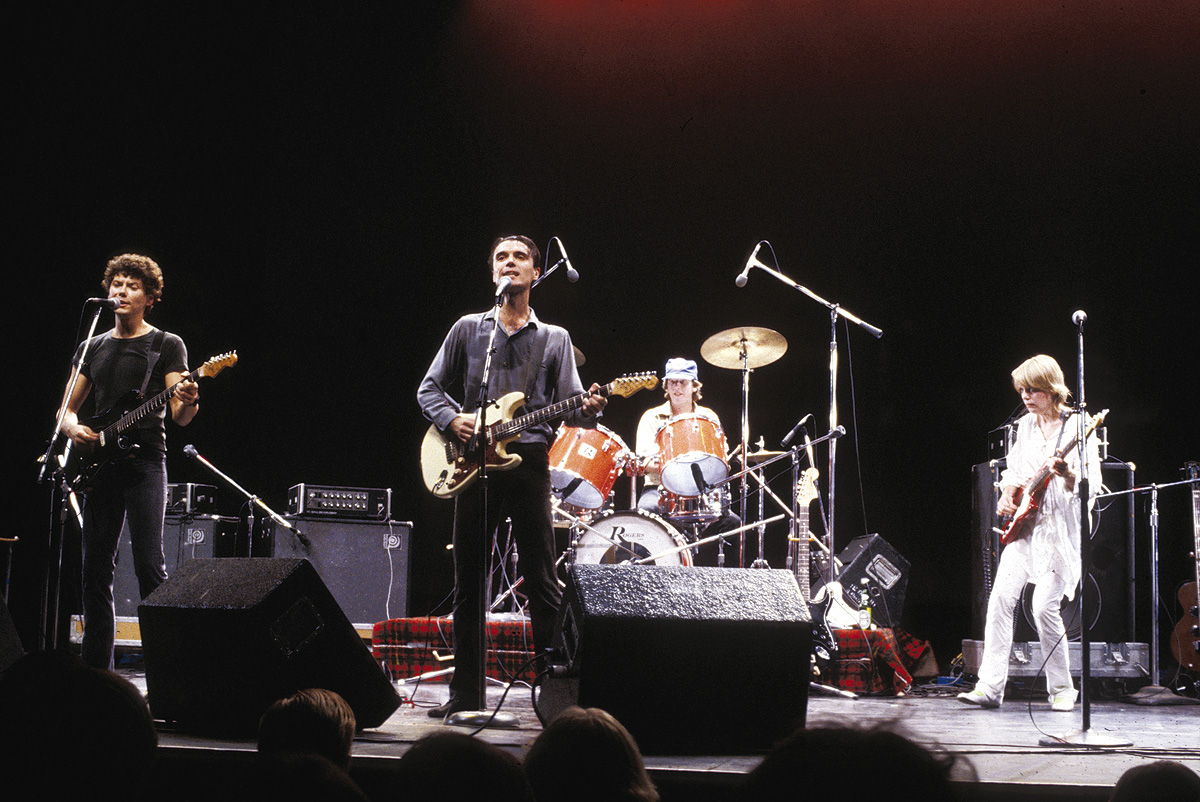

So. In gnarly guitar music and existential Japanese literature, The Wind-up Birds have all the right reference points covered. On record they sound extraordinary; scorching and caustic, Cribs-y guitars (what is it about Yorkshire?), a band banging on and hanging on for dear life – together (always together) – as their singer vocalises about moral panic and telling good guys from bad, shouting in all the right places but knowing when he needs to take it back.

The Wind-up Birds – Guards

Guards, their new single/focus track (gads) sounds like the sort of thing I might’ve unwittingly taped off of the John Peel Show while letting the tape run on after capturing the latest Inspiral Carpets session, a track that I’d then spend the next 35 years trawling the corners of the internet in the vain hope of finding out more about. No need to spend half a lifetime wondering what that great new track was – these days it’s always Guards by The Wind-up Birds. Not out until mid-November, you can play it repeatedly here. Listen out for it on the more discerning radio shows of your choice. And watch them go. Fly, even.