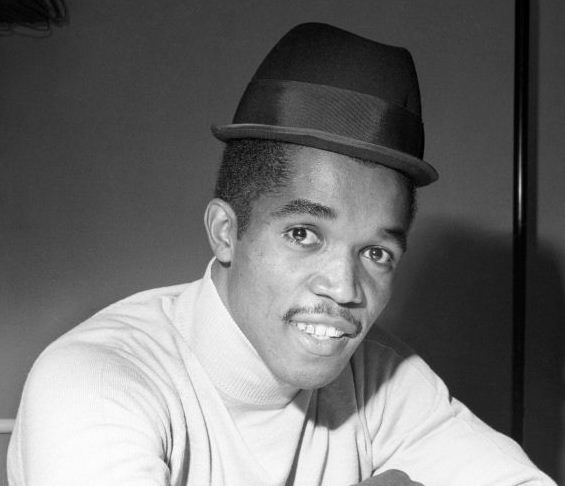

Isaac Hayes created plenty of great music. The Black Moses album…Ike’s Rap…his reinterpretations of By The Time I Get To Phoenix and Never Can Say Goodbye to name just some, but his signature tune is undeniably Theme From Shaft, 1971’s hi-hat ‘n high groove exercise in funk. Damn right it is.

It’s generally accepted too that Curtis Mayfield’s Superfly is one of his greatest albums. A groovy stew of stabbing brass, skulking street panther bass and wah-soaked guitar lines that add musicality and danceability to hard-hitting socio-political lyrics, it followed hot on the strutting cuban heels of Shaft and reset the bar for musicians soundtracking films.

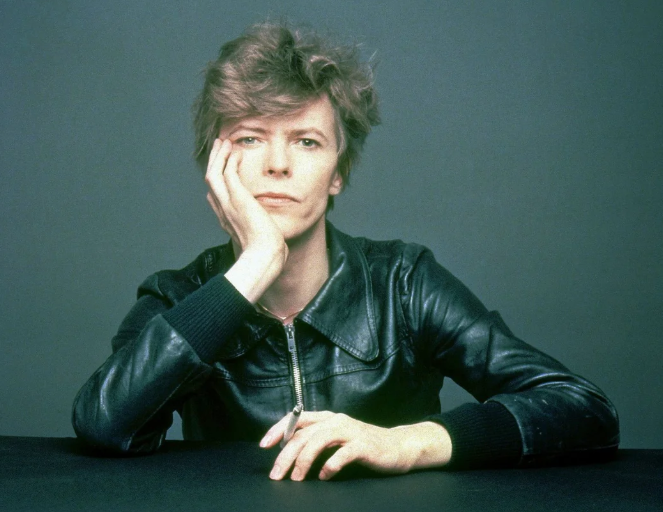

And then came Marvin Gaye.

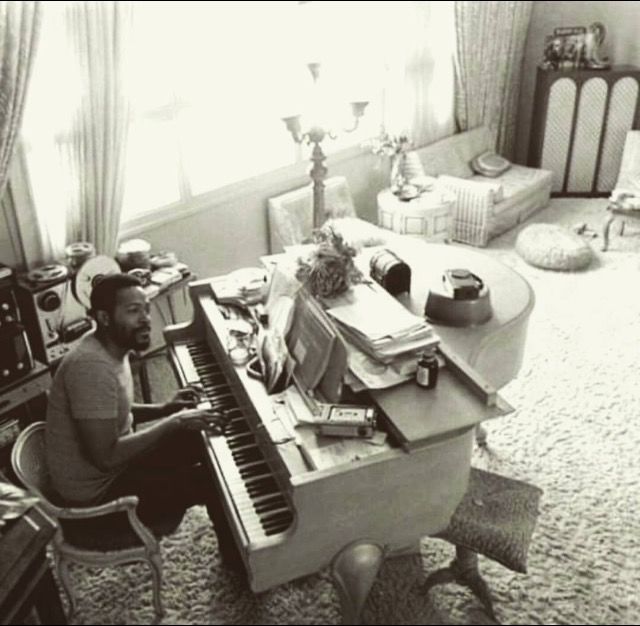

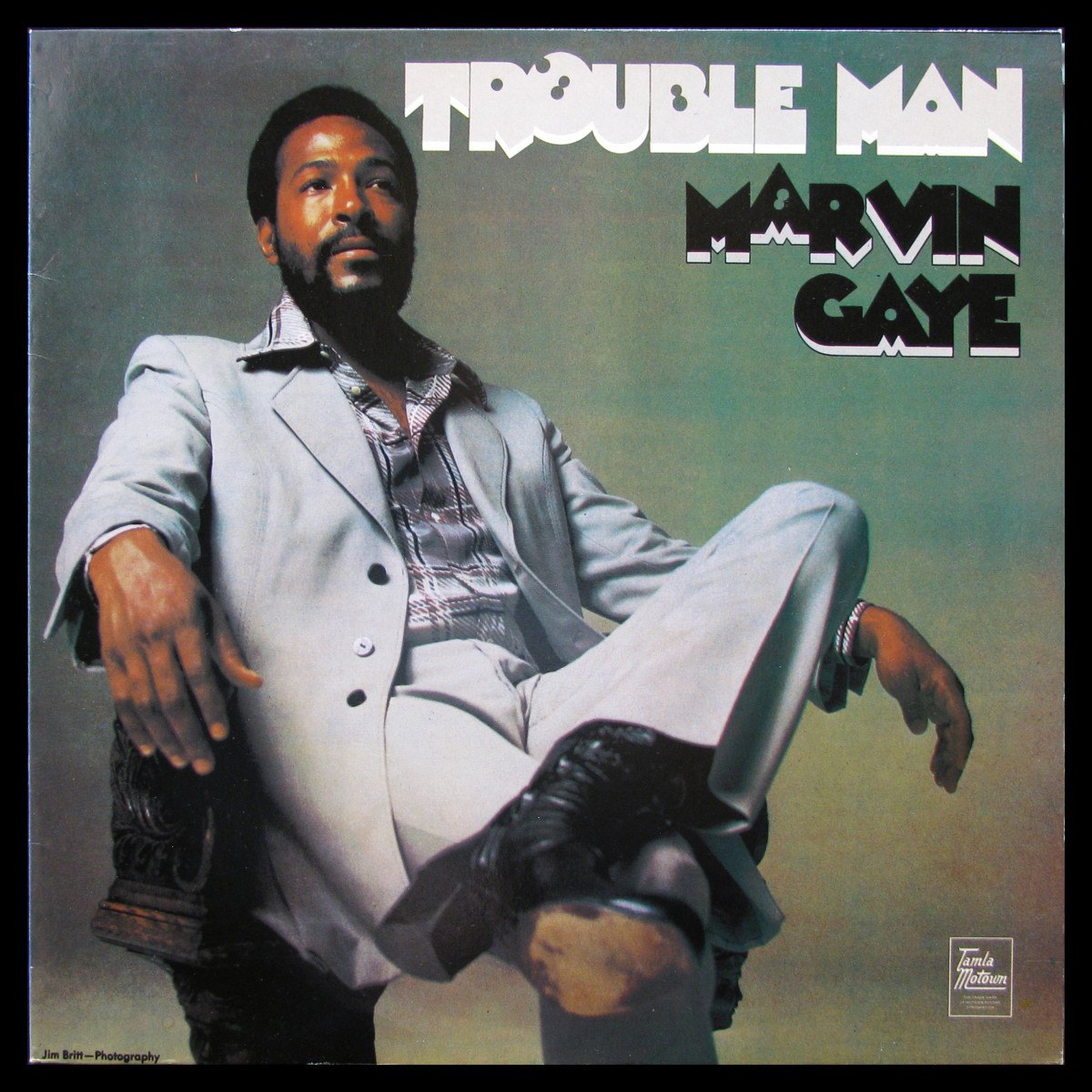

Emerging from the success of What’s Going On, with credit in the bank and a new Motown contract offering him complete editorial control over his work, he was offered the opportunity of scoring blaxploitation flick Trouble Man. The producers had been quick to spot the pros of hitching a movie’s soundtrack to a respected musician and Marvin was equally as excited at the prospect of making exactly the sort of record he wanted to make.

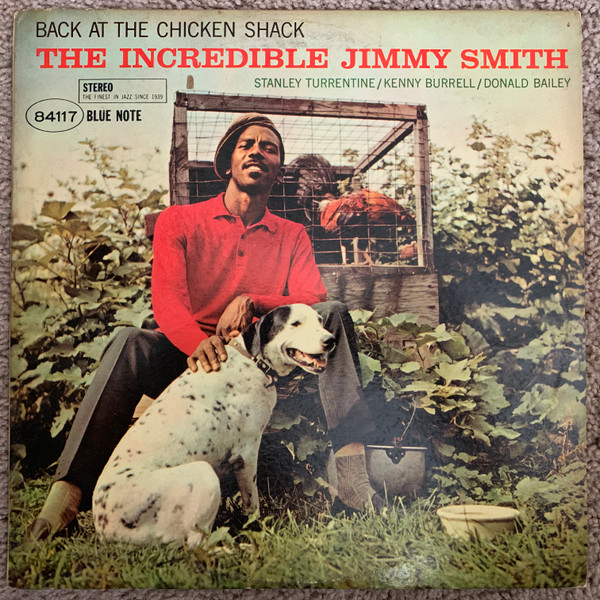

His score for Trouble Man not only builds on his contemporaries’ fantastical funk ‘n soul infused soundtrack work, it also has its own personality, veering left to take itself down interesting roads in jazz-inflected atmospherics. Gaye, with his new-found artistic control, hired the Funk Brothers, Motown’s in-house band and augmented them with the cream of L.A.’s jazz scene. The result was a jigsawing of slick soul guitar riffing and solid ‘n steady on-the-one basslines to whip-smart polyrhythmic drums, nerve jangling piano and rasping brass. Underscoring all of it is hotshot film score arranger Gene Page’s sublimely shimmering string lines. A soundtrack it may be, but it works well as an album in its own right.

Is it a soul album? A funk album? A jazz album? Yes, yes and yes. And, just as Isaac and Curtis had done before him, Marvin rewrites the rule book for scoring films in the 1970s. Would Bernard Herrmann’s exquisitely anxiety-inducing Taxi Driver score be just as jarring, just as dramatic without him having Trouble Man as a reference point? That’s debatable.

Trouble Man – movie trailer voiceover

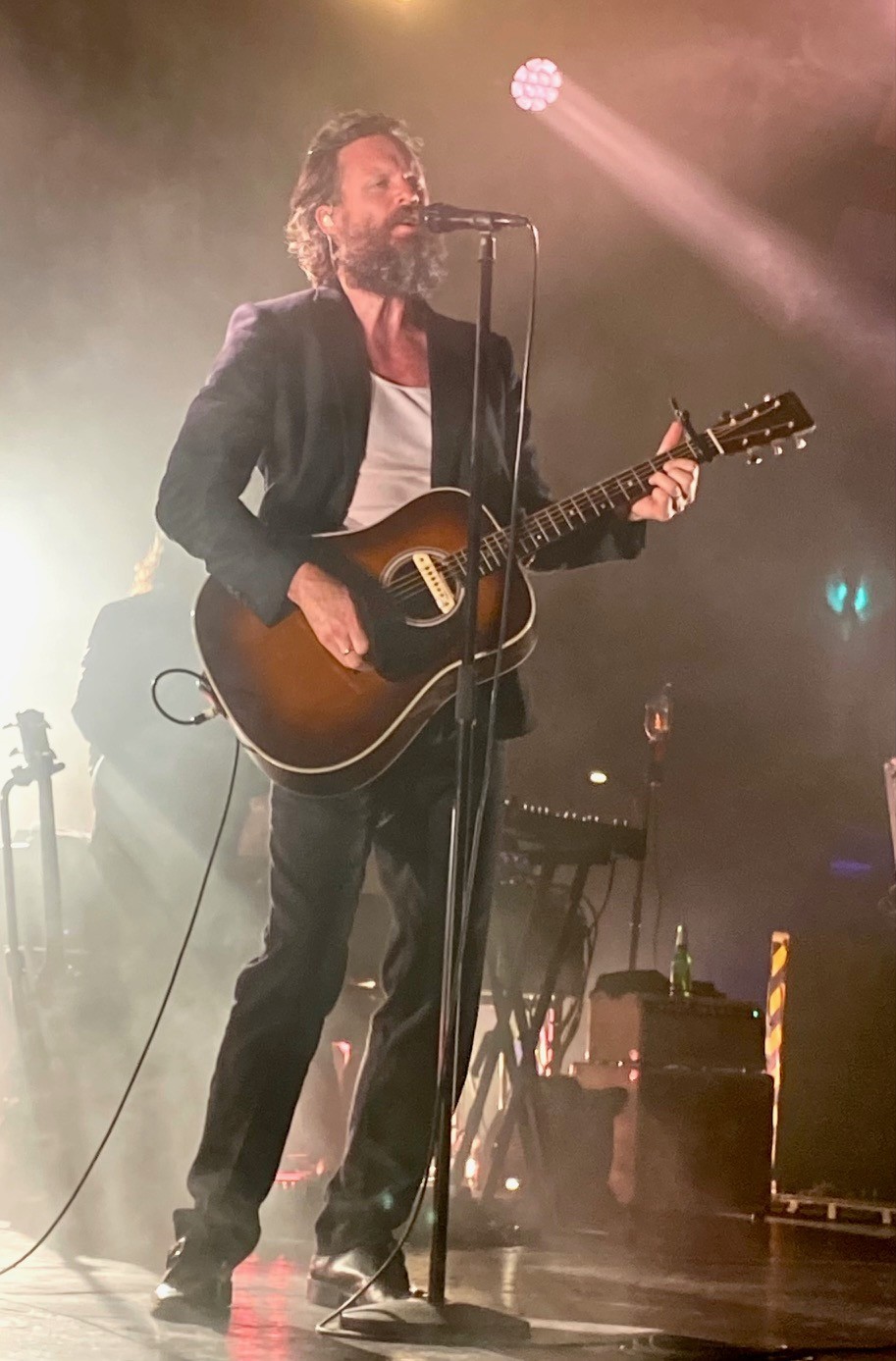

Trouble Man (the title track) popped up on Guy Garvey’s 6 Music show a week or so ago and, like all the best music, had me replaying and reappraising it for more than a few days.

Marvin Gaye – Trouble Man

It’s a beauty, isn’t it?!

That drum sound! So crisp, so exact. That’s the sound of Stix Hooper (possibly not his real name). The whole track hangs on his airy dynamic clatter… that, and the ominous register of strings… and the clanging piano’s chords of doom…and the anticipatory brass…and ubiquitous vibraphone. And especially Marvin’s killer vocal. You know that cliche about singing the phonebook? Yeah, well Marvin could sing the entire contents of Berry Gordy’s Rolodex and you’d never tire of listening to him.

I come up hard, bay-bee, but now I’m cool

I didn’t make it, sugar, playin’ by the rules.

Marvin is double-tracked for much of the song, one vocal in low register, the other offering the high and floaty falsetto that adds lightness to the heaviness of the music. Coupled with the swing of the drums, it creates real finger clickin’ hipness in the verses and high drama in between.

The guitar – played by Ray Parker Jr – mirrors the piano line and grooves on a smooth and sliding repetitive E minor riff. Sure, young Ray could very probably break out a slick jazz break or an augmented chord progression without breaking so much as a bead of sweat, but he’s here to serve the song, not to kill it in unnecessary noodling fluff. He stays well within his lane and the song is better for it.

At the chord changes, muted trumpets get on board, creating tension and dissonance that mirror Marvin’s lyric.

There’s only three things, that’s for sure:

Taxes, death and trouble

The trumpets freeform through the heady stew. The strings ramp up the anticipation and the anxiety and then, just as release always follows tension, Marvin’s high and carefree ‘Ye-eah!‘ breaks the spell and we’re back to the groove.

The track swings on.

Marvin breaks into a proto rap:

I know some places

And I see some faces

I got good connections

They dig my directions

What people say, that’s okay

They don’t bother me.

Stix Hooper continues to do his own thing; a cymbal splash here, a snare fill there, a full kit paradiddle in the funky gaps. The strings and brass continue to induce anxiety. The vibes serve as an aural lightbulb moment, the ‘ah! everything’s ok again!’ moment. The bass playing slides up a notch. The whole thing grooves. Trouble never sounded so goddam danceable and airy and exciting.

And Marvin, cool, street-smart and determinedly ploughing his own unique furrow, brings it all back to a sweet-vocalised close. Astonishing music.