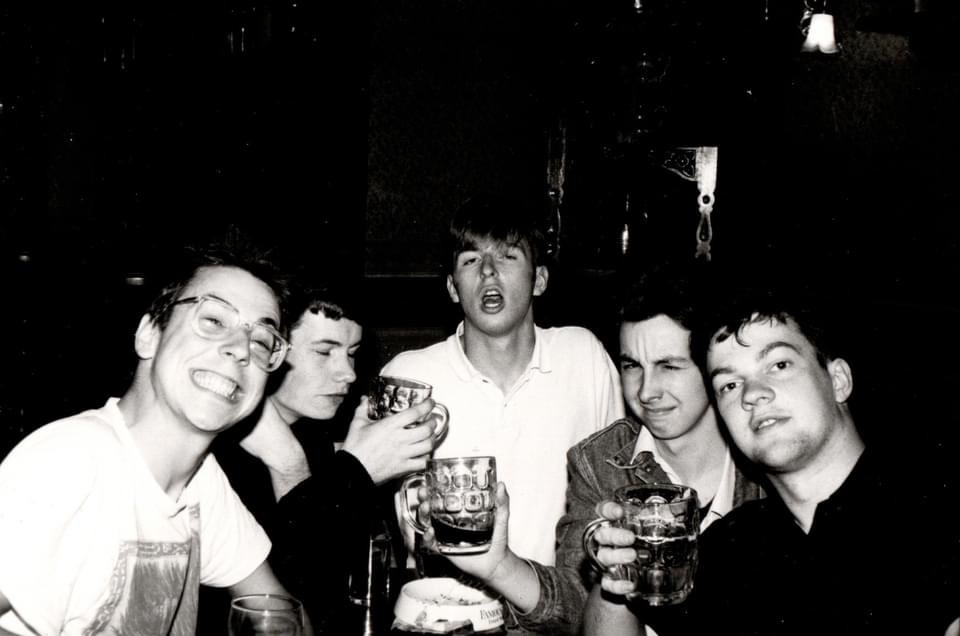

It’s 1990. Or maybe 1989. Maybe even 1991. That kinda timeframe though. It’s a Wednesday night. Not a night we’d normally be in the Crown, but there we were. I’m guessing it was during the holidays, when some of us were free of studies and had a decent stretch of summer ahead of us. Or maybe it was in the middle of winter but we had a gig looming and had squeezed in an extra rehearsal in addition to our usual Monday night slot. Either way, and for whatever reason, we were wedged in around one of the Crown’s circular tables, up there at the back, in our usual spot with all the other like-minded Irvine hipsters of the day, pints in hand and conversation flowing around the exclusive subjects of music, films and football.

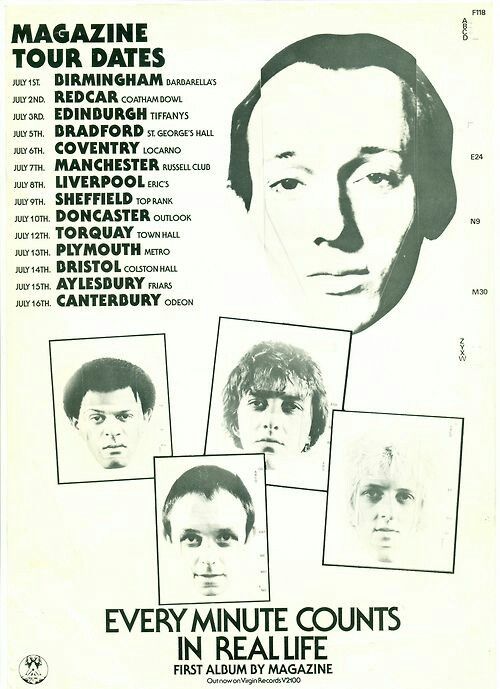

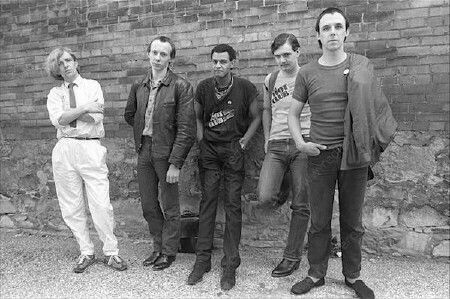

One of us comes back from the pub’s spartan toilets with the unlikely but true news that none other than Feargal Sharkey is presently at the bar. Nowadays Feargal is everyone’s favourite political activist, but back then he was Fucking! Feargal! Sharkey!, parka-clad vocalist in The Undertones, laterally the suave, Ferry-haired-and-suited crooner of A Good Heart and (even better) You Little Thief; a genuine pop star and hero to every single one of Irvine’s assembled guitar stranglers and tune botherers that frequented the Crown. Why would Feargal Sharkey be in the Crown? In Irvine? On a random Wednesday night? A rumour creeps up to our table and taps us on the shoulder.

“Apparently, he’s up to check out a band for Polygram. I’ve been told they want to sign the Surf Nazis.” The rumour looks at me with a smirk. “It won’t be the fucking Sunday Drivers, I can tell you that for nothing.” Everyone is watching Feargal, supping his pint at the bar with all the casual indifference of any of the hardened locals. “It might be the Thin Men he’s after. They say loads of labels are after them.” The Thin Men are from Stewarton, not Irvine, and that prickles. As it goes, a few years down the line, they’d change line-up and name and become Baby Chaos. Happy Mondays’ manager Nathan McGough would look after them, Warners would sign them and they’d have minor success. But anyway. Back to Feargal.

No sooner has the rumour sloped off to the next table, than the bold Paul Forde, always on the right side of being slightly pished, makes his way to Feargal. We watch as our self-appointed diplomat and representative strikes up a conversation that’s over and done with between two sips of Feargal’s pint.

“I told him that Wednesdays weren’t particularly good for him,” says smart-arsed Paul, referencing The Undertones’ Wednesday Week, “and then asked him what the fuck he was doing in Irvine.”

As he finishes telling us this, Feargal downs the last of his pint and vanishes, ghosting out just as invisibly as he ghosted in. We never did find out why the fuck he was in Irvine, in our pub, in the middle of the week, in a room full of eager musicians but with no live band playing. Sorry if you were expecting a punchline. Not much of a story really, but a big story for Irvine.

Fast forward to 2015. It’s a Thursday night this time. October 15th. But that’s not important. I’m in Kilmarnock’s Grand Hall. The sainted Johnny Marr has finished a storming gig and I’m given the job of taking pictures on all his fans’ cameras as they line up to meet him. His tour manager has set up a wee wireless Bose speaker and cued up a playlist, carefully curated by Johnny himself. Chic’s rinky dink disco rattles out of it. Some early Talking Heads. Wire. Johnny patiently pouts and preens for his people, occasionally nodding his head in time to the beat in the background. Clang! A Hard Day’s Night rushes past in a riot of melody and guitars and vocals and Fabness. Next, Buzzcocks cut loose. “I hate Fast Cars,” sneers Pete Shelley, the iPhone in my hand silently click-click-clicking as Johnny pulls plectrums from the wee right hand pocket in his jeans and gives them to the girls.

Then, a brief 5 note electric guitar riff, edged in feedback and promise eases in, and even before the drummer’s clatter has signified the true start of the song, both Johnny and myself have been stopped in our tracks.

The Undertones – You Got My Number (Why Don’t You Use It)

“Oh yeah!” says Johnny with a smile and, like any true fan of music, indulges in a little unexpected air guitar as the song’s punkish riff runs its way across the fretboard. Within seconds, his enthusiasm has caught on and I’m bobbing along to the bounce of the beat, Johnny grinning at me with his recently-whitened teeth. ‘Well, this is all quite surreal and magic,‘ I’m thinking.

It’s a great track, full of hooklines and riffs, dumb-but-essential ‘duh-dit‘ backing vocals and that terrific call and response ‘if you wanna wanna wanna wanna wanna have someone to talk to‘ line between the singing Feargal Sharkey and John O’Neill on guitar. It’s stoppy-starty, it has just the merest hint of Louie Louie-type stabbing keyboard towards the end and it’s all over in a metallic crash of symbols and Feargal’s definitive “WHY DON’T YOU USE IT!” shout at the climax.

Listen and repeat. Listen and repeat.

Listen and repeat.

Listen.

Repeat.

When you tire of The Undertones, you tire of life.