‘Busboy’…’bellboy’… ‘waterboy’ …’shoeshine boy’…the reason African Americans began using ‘man’ as a full stop in conversation is there for all to see. Fed up of being treated as subordinates by their white bosses, jazz musicians and those in the service industry which enabled their scene to thrive called one another ‘man’, the inference – the point being – that you are very much the equal of the guy ordering you around. Damn right you are. Never forget it, man.

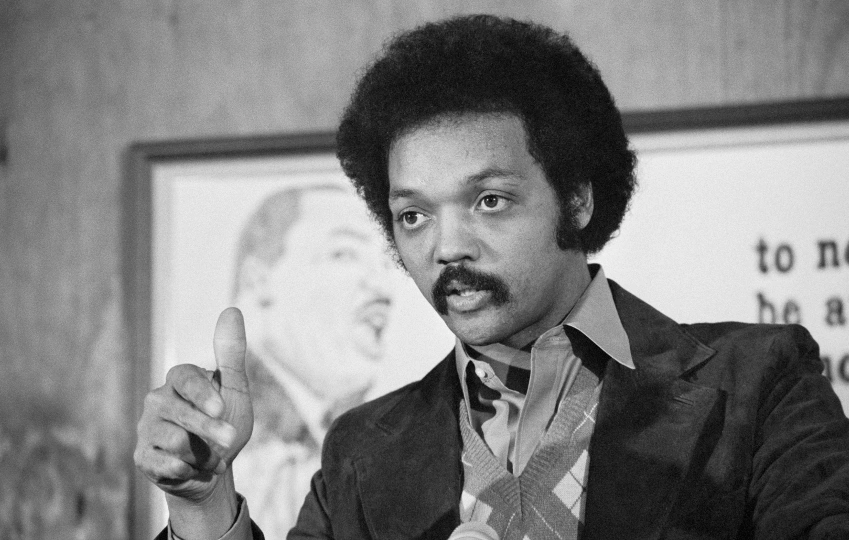

Jesse Jackson, the U.S, politician and activist who died last week, took this notion one step further. At his rallying speeches across a divided and tense States, he would punctuate his measured, proto-rap with a simple but powerful statement; “Never forget; ‘I am somebody. Respect me. Protect me. Never neglect me. I. Am. Somebody.’”

Born after his mother was raped by a neighbour, Jackson grew up living next door to half-siblings who would never know exactly who their young neighbour really was. Shunned by his natural father, Jesse Jackson more than anyone else entered adulthood understanding precisely the true meaning of ‘I am somebody’.

He worked tirelessly within the black communities of Chicago, fighting for desegregated schools, social housing and, working alongside Martin Luther King jr (he was with King in Memphis when he was assassinated), organised boycotts of whites-only shops/stores until the owners were forced not only to open their doors to all, but to actively employ people of colour. Jackson galvanised entire communities to stand up for equality, demand justice, fight for change.

Delivered in a blur of denim and suede and more than a casual approach to the use of shirt buttons, his early speeches were full of clenched fists, bared teeth, wild eyes …and absolute clarity. Go and watch them on YouTube. They were electrifying and rousing. It’s hard to relate them to the same person, the smart senior dressed in a navy blue suit and campaigning his way towards the White House a couple of decades later, but there’s Jesse; angry, fired-up and fighting for his people.

If you didn’t know, you might be forgiven for thinking these sort of speeches all occurred at some arcane point in history, around the time of Henry Ford’s Model T and Charlie Chaplin and southern state lynchings, y’know, before we knew any better, so it’s sobering to consider that the speech below was delivered in 1972, years beyond the advent of the automobile and hooded ‘Christians’ with arson habits…and very much in my lifetime. Probably yours too.

It’s all the more sobering – shocking even – to contemplate that the words spoken above still, in an oppressed, Trumpian, ICE-driven American society, ring with righteous anger and rage, a hundred years and more since the Model T Ford and silent movies and burning crosses first permeated American life. What’s really changed?

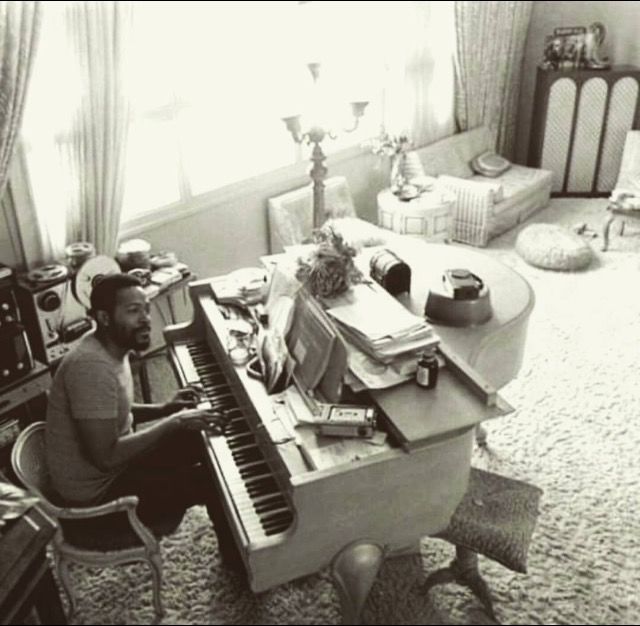

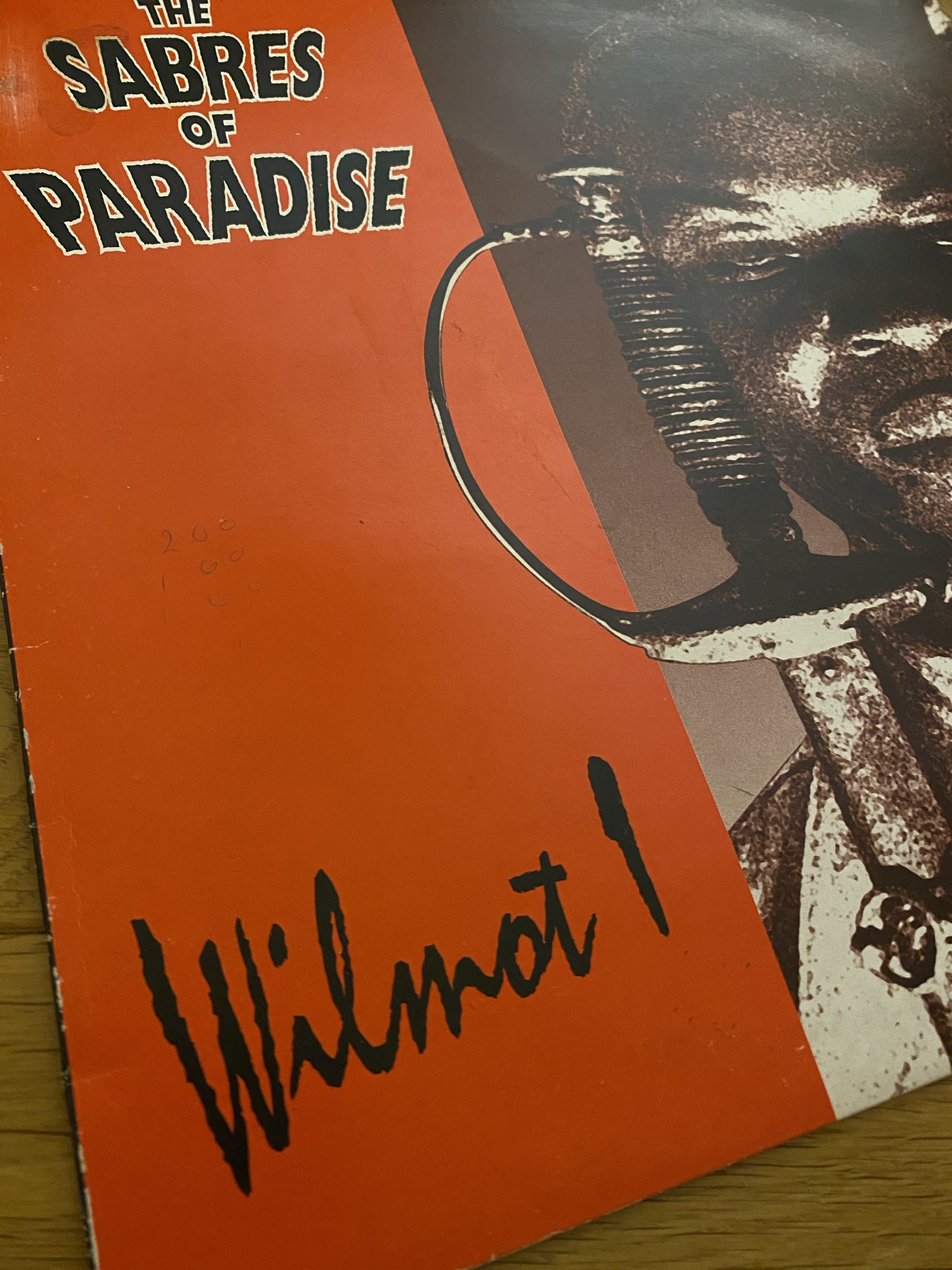

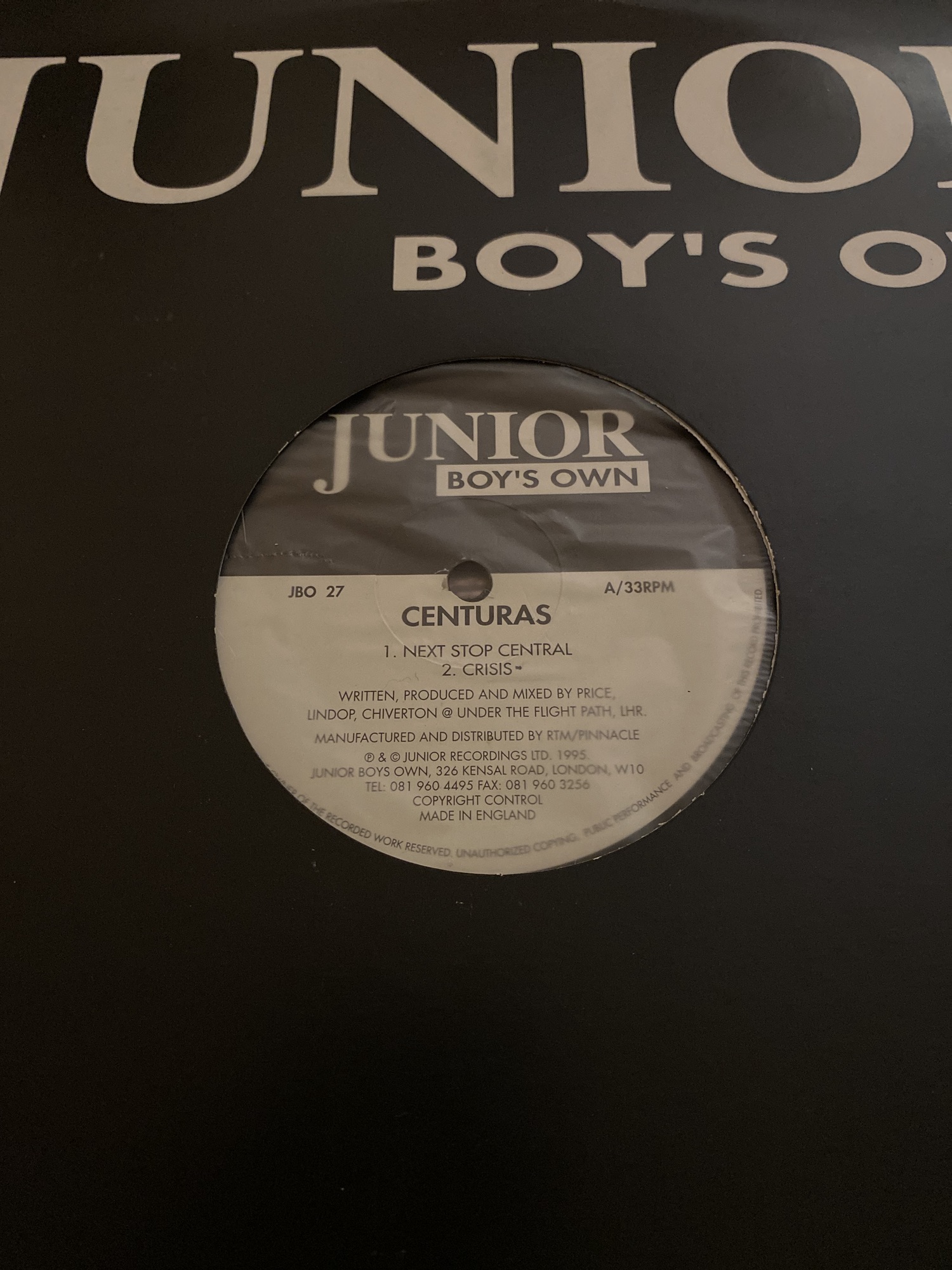

The speech above is – as you well know – the same speech that’s sampled on Andrew Weatherall’s remix of Primal Scream’s Come Together. Taken from the 1973 soundtrack release of the Wattstax benefit concert in L.A., it samples Jackson as he addresses 112,00 people in the Memorial Coliseum one balmy August day. Ensuring affordability and access for all, your $1 ticket got you a day’s music in the company of The Staple Singers, Carla and Rufus Thomas, The Bar-Kays, Isaac Hayes, Albert King – or as Jackson stated, ‘gospel and rhythm and blues and jazz…all just labels…we know that music is music…’

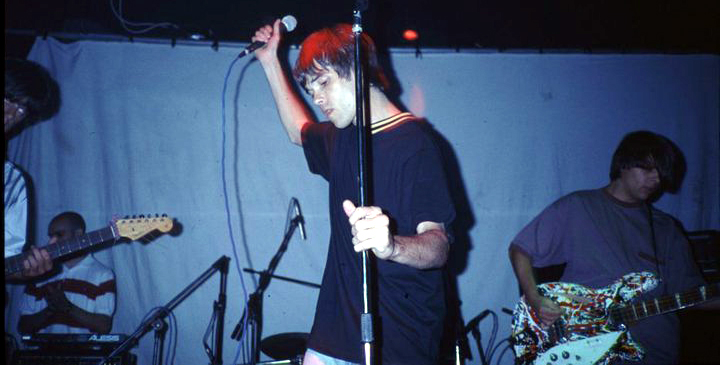

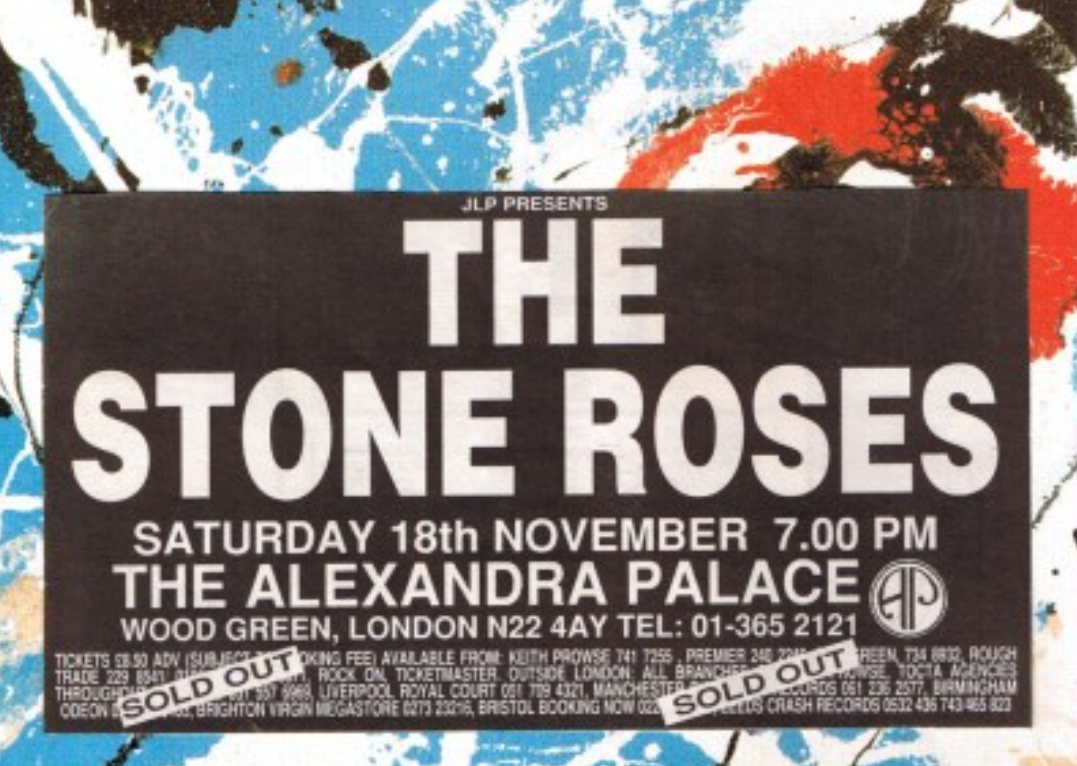

Primal Scream – Come Together

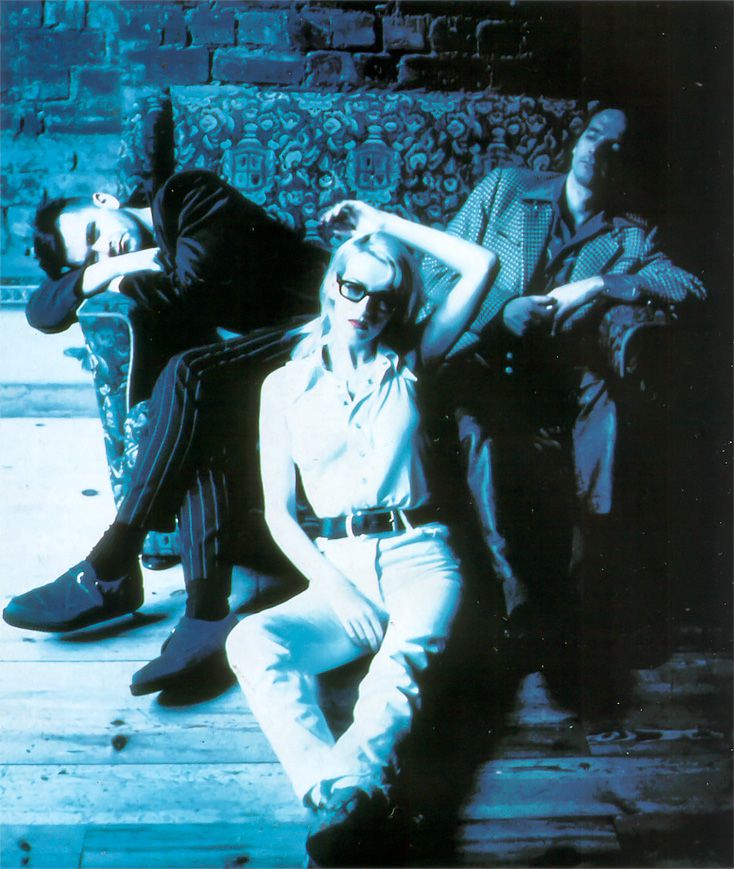

Weatherall’s sample is inspired, turning Primal Scream’s original (and very good) version of a gospel tinged, southern-fried heartbreaker – all heavenly trumpets and guitars dripping with the salty tears of Suspicious Minds – into a brewing and bubbling, long-form epic that very much imbues the spirit of 1990’s anything-goes/togetherness house music scene.

Even yr local indie disco was prone to dipping their Doc Martened toes into the world of repetitive beats. It wasn’t that unusual even then to have Voodoo Ray pop uo between Voodoo Chile and It’s A Shame About Ray. Three disparate records, one cutting edge dance music, one classic rock and one indie rock…but all just labels. Music is music is music, after all.

Baptist minister, two runs for President, agitator, organiser, educator: the world needs more Jesse Jacksons.