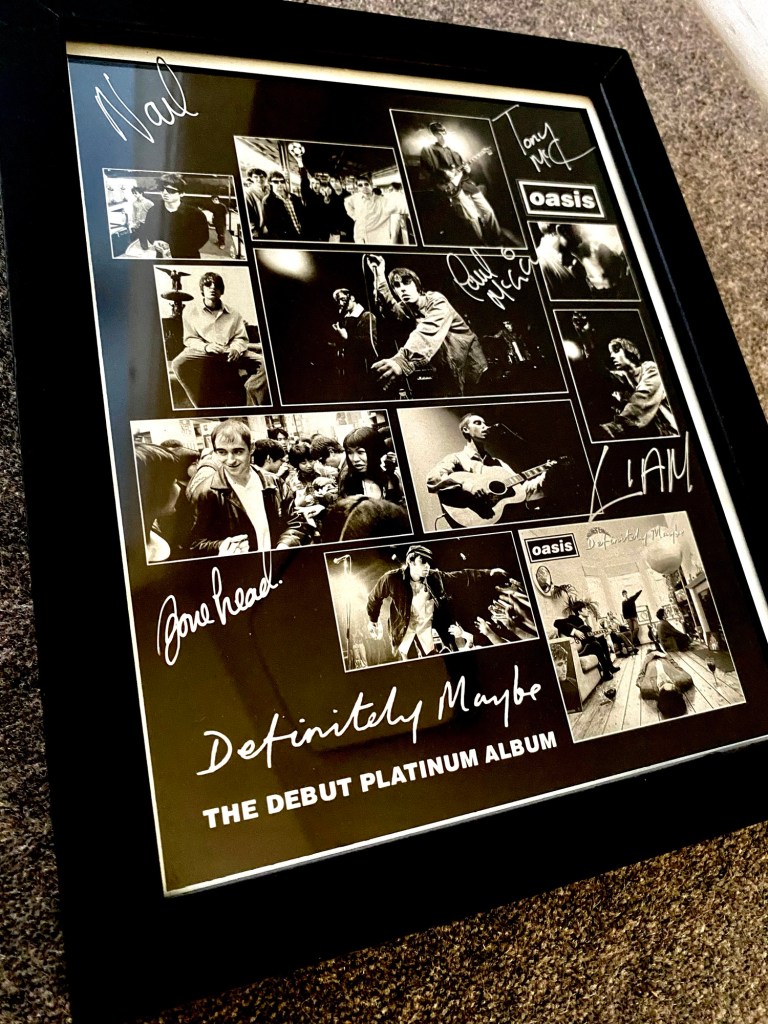

In a massively popular band. Breaks them up and forms misunderstood follow-up group. Subsequently begins third phase of career and releases everything under his own name. There are side projects, guest appearances, mentoring roles with younger musicians, low-key soundtrack work…all the while maintaining a very decent public image.

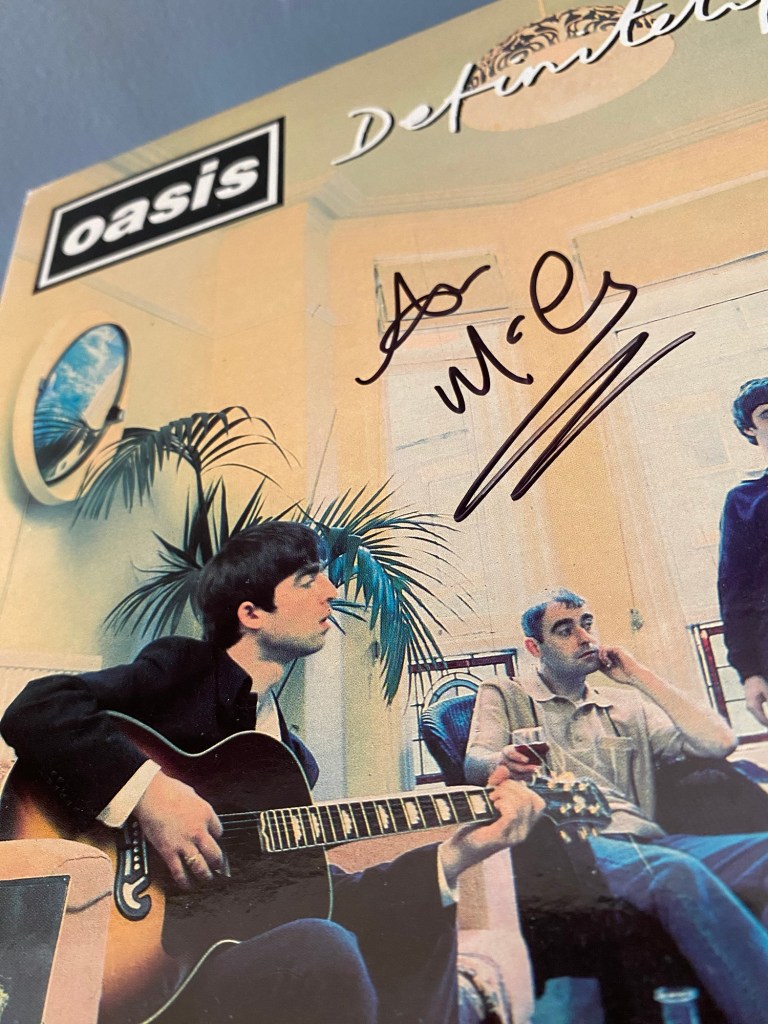

Are we talking about Paul McCartney here, or are we talking about Paul Weller?

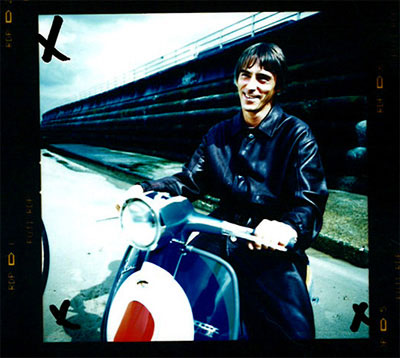

The statement applies to both, of course, but there’s inarguably a considered difference that whereas McCartney’s solo work is – and will always be – massively overshadowed by his first band’s output, Weller’s solo output is nothing less than the equal of – and possibly even greater than – what’s gone before. Yeah! Fight me! I’m talkin’ to you, you with the tragic, balding feathercut and too-tight Gabicci top. Let’s clear the air ya silly auld mod.

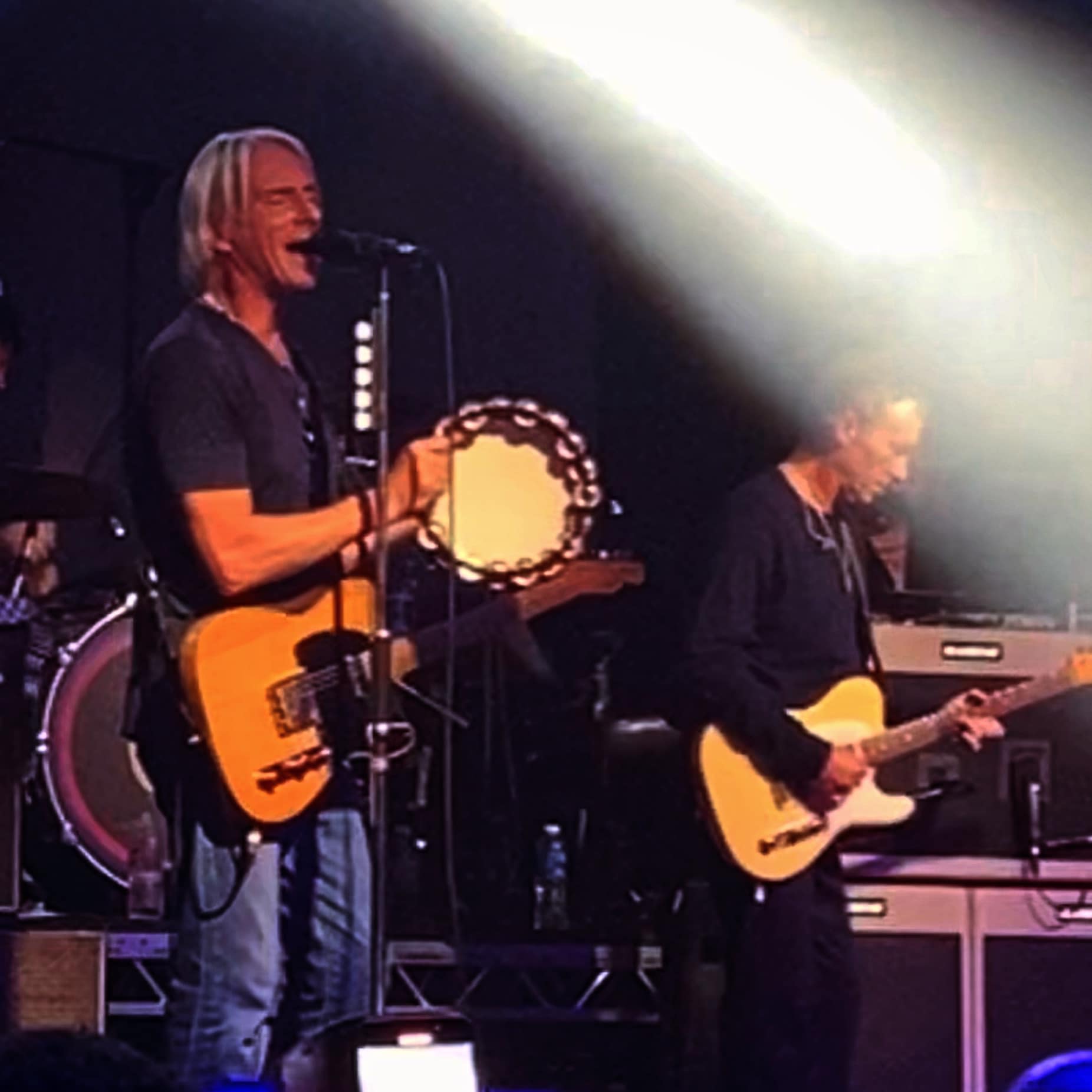

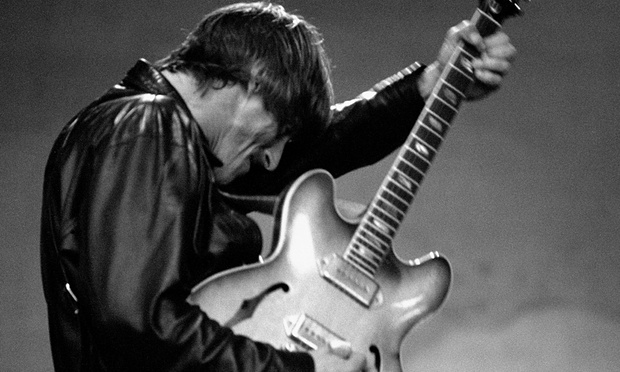

Never was this clearer than mid-set in the Barrowland Ballroom last night, when in a quadruple wham-bam, thank you ma’am, Weller reeled off Hung Up into Shout To The Top into Start! into Broken Stones – two of his finest solo works bookending two of the finest releases in his first two groups’ recorded output, all played to within an inch of their note-perfect lives. You don’t need me to tell you how great Welller’s Small Faces infatuation makes itself known in Hung Up‘s soulful and gospely middle eight. You don’t need reminding of the joy of living breeziness that burls Shout To The Top to its stabbing and symphonic conclusion. You already know how tough-sounding and razor-sharp his SG sounds on Start!, its Beatlesy psychedelia never more obvious than when shoved in your face at maximum volume. Or how Broken Stones as it’s played tonight could have been arranged with a prime time Aretha in mind.

Weller is a magpie. He takes all the good stuff, boils it into a groovy stew and makes something new and equally vital from it. He started like that, way back when, when nicking Motown riffs for Jam songs. He continued this with the all-in policy of the Style Council; Blue Note to new note, whether you liked it or not. And he continues to this day, releasing with unbelievably metronomic regularity interesting and unique records; records stuffed to the gunnels with crackling electronica, frazzled guitars, deep house grooves, neo-classical ambience and whatever the fuck he likes. He surrounds himself with proper players who can help him achieve his sonic vision. He tours relentlessly. He’s one of our very best and we should never take him for granted.

I was going to review last night’s show but, to be honest, I’d already written the review three years ago, when Paul Weller was last at the Barrowlands. On early and off right at the stroke of curfew, back then he played the sort of back-cat trawling and sprawling set that might have Springsteen looking over his shoulder in apprehensive appreciation. Old favourites sat shoulder to shoulder with new stuff, guitar wigouts sat next to piano ballads, smash hit singles made way for indulgent jams. The set then was perfectly paced, as it was last night; Have You Ever Had It Blue? sounds terrific in the old ballroom. Headstart For Happiness, Changingman, Village, the old, the new, side by side and never sounding better. A gnarling, spitting Peacock Suit has, like the singer himself, proper bite. There’s political charge. A pro-Palestine speech garners a healthy swell of solidarity from the never less than right-minded Glaswegian audience.

But it’s the encore that floors me.

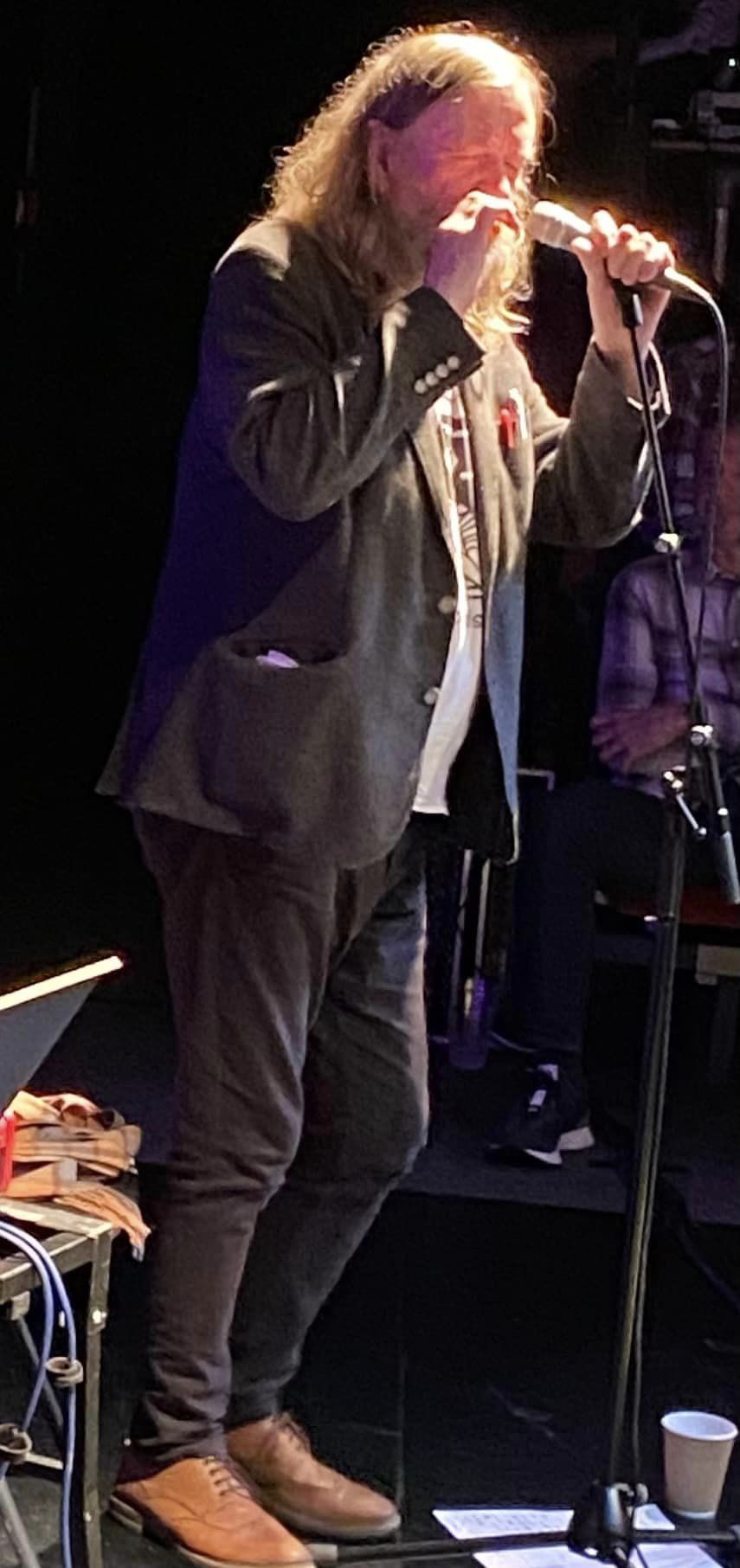

We’re expecting That’s Entertainment and Town Called Malice, his chosen double knock-out show-stoppers for the past couple of tours, but before he gets to these, Weller breaks into Rockets, the closing track from On Sunset, an album that’s already four years old and, as I’ve began to appreciate, matured nicely since being released. Rockets, it transpires later, isn’t on the set list. Weller, in a fit of spontaneity rarely present in live shows these days, pulls it out of the air for the first time on this tour. As it unspools, it dawns on both Mrs Pan and I that Rockets is Weller’s Bowie moment.

Paul Weller – Rockets

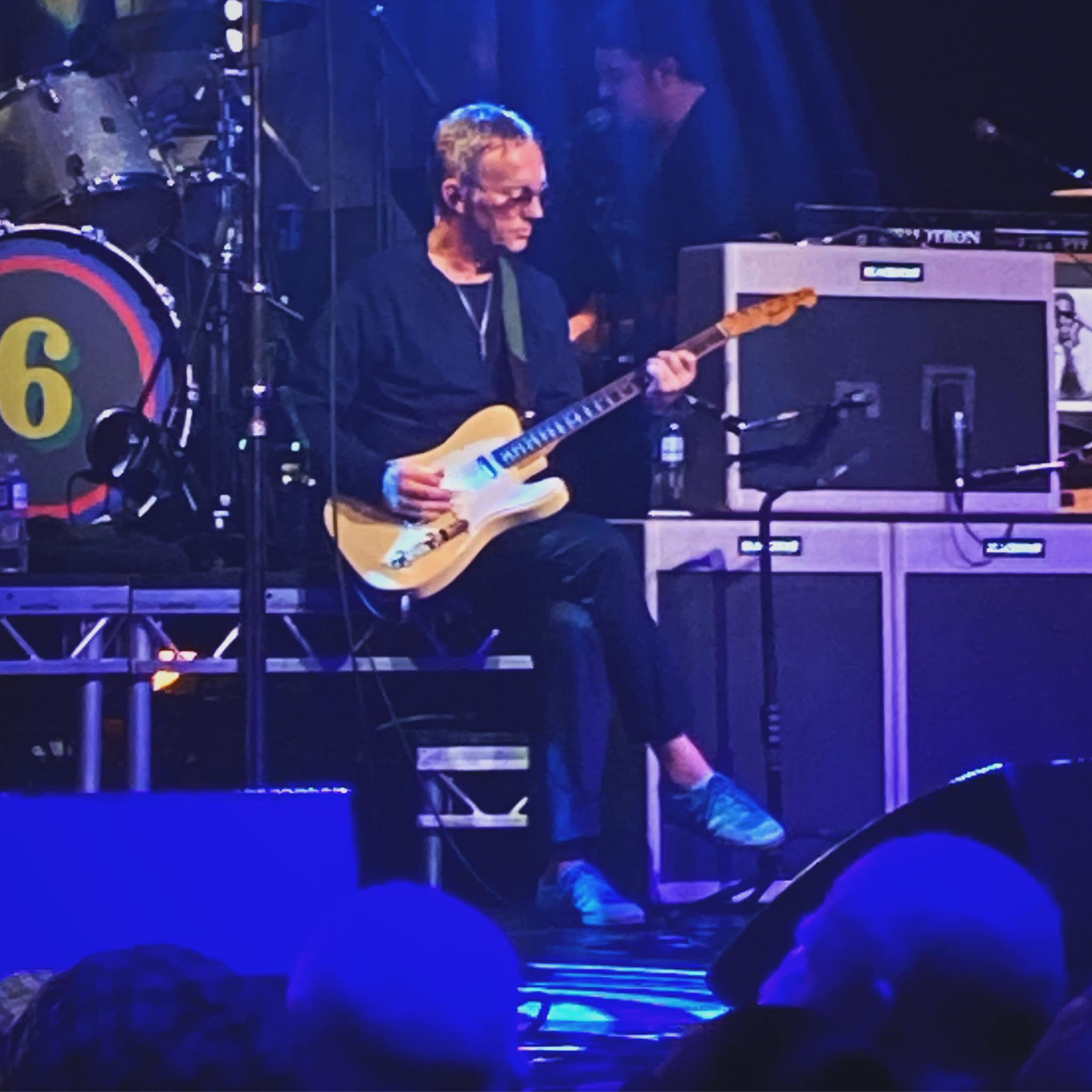

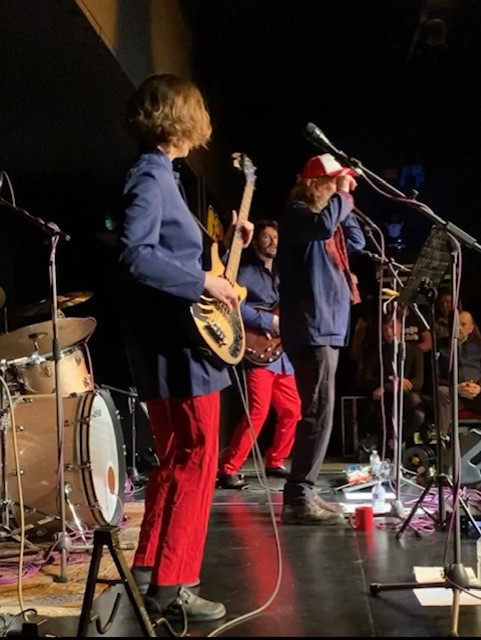

It’s slow and acoustic, the singer accompanying himself in front of some tastefully understated percussion. He shifts from major to minor key and a churchy organ shimmers its way in, Weller’s voice woody and hollow and powerful. Man, it’s powerful! By the second verse, Steve Cradock has joined in, his clipped fuzz guitar accentuating the beat. The bass player is all eyes a-closed and playing by feel, lost in the music as the Barrowlands’ glitter ball shoots little diamonds of light across a gobsmacked audience. Jacko Peake eases in, his bah-bah-bah-baritone sax punctuating the pauses in the vocals. The strings – synthetic in the Barrowlands, full-on symphonic on record – glide in, carrying us home. Weller’s melody is slowly unravelling towards a coda where the Bowie feel is total and wonderful and complete. Singing over, the track swells to a long and stately close, little Stevie Cradock playing some cracking morse code notes and, between furtive gasps of his vape (!), some lovely elongated slide guitar parts. It was all fairly breathtaking, it has to be said, and that’s before Weller’s sock it to ’em one-two encore that followed immediately afterwards.

I seem to write this every time I review Paul Weller, but I’ll say it again; if he’s within 200 miles of where you live, find a ticket and go, go, go! Paul Weller is at the absolute peak of his game right now and you don’t want to miss him.