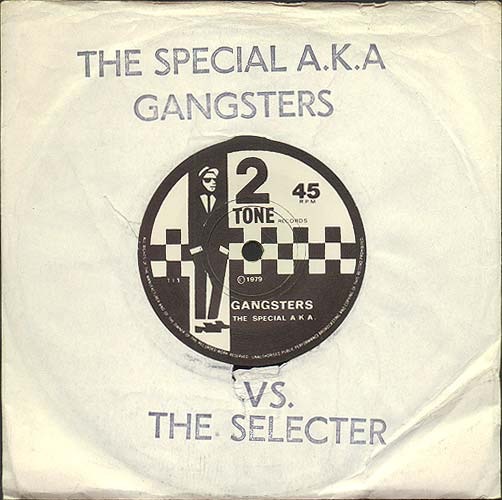

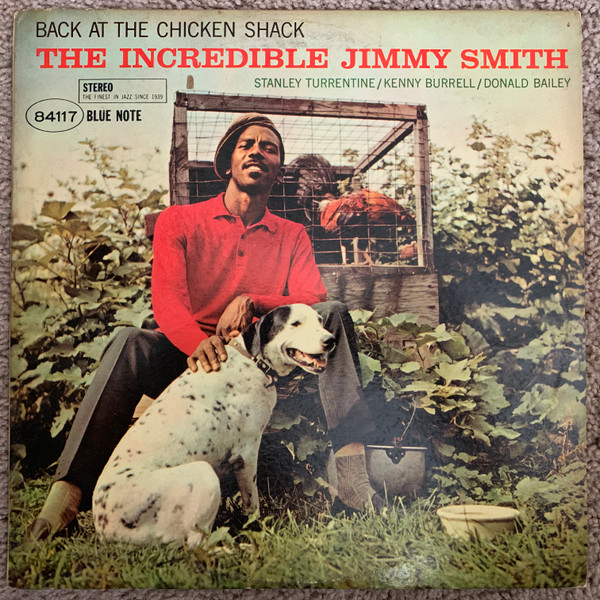

Gangsters by The Specials… (or Special A.K.A., to give them their full original name). It’s just about the most perfect distillation of its times. Punkish and idiosyncratic with a generous nod, in both sound and vision, to what had gone before, it served not only as a stall-setter but a rallying cry for 2-Tone and the many brilliant things that would shortly follow on the label. Specials’ release number one…2-Tone release number one…what an entrance.

The Special A.K.A. – Gangsters

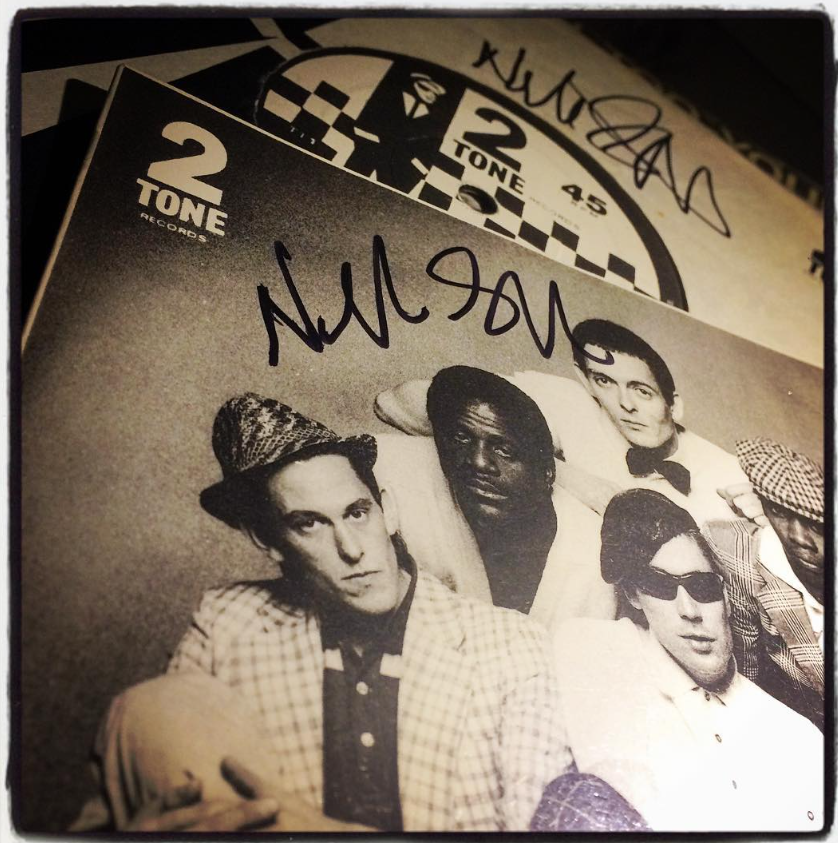

I once asked Neville Staple to sign my copy of Gangsters. My copy isn’t one of those first few thousand hand-stamped ones – of course it’s not, I was only 10 when it was first released and I wasn’t yet in the habit of skanking at 2-Tone shows where I might’ve bought one, but my pocket money stretched to a 7″ single every now and again and in amongst the Madness and Beat releases that I did buy at the time, I somehow also ended up with a copy of Gangsters, housed in the iconic 2-Tone Walt Jabsco sleeve, which no doubt attracted my magpie eyes and fertile young mind when browsing the racks of John Menzies in Irvine Mall.

Anyway, Neville.

He was appearing at Seaside Ska, an annual festival I was involved in the promotion of. I’d asked him pre-show if he wouldn’t mind signing a couple of my Specials singles and he suggested I drop in to his dressing room for a chat at the end of his performance and he’d sign them then.

Post-show, I rapped on his dressing room door.

“Joost a minute, moyte,” came the shout from behind the cheap plywood exterior. And then, almost immediately, ‘S’all roight…joost coom in.”

Neville was standing in a pair of large white Y-fronts and, apart from the pork pie hat atop the dreads and the heavy gold chain around his neck, nothing else.

Where did you get that blank expression on your face, as someone once sang.

At least, I hope I managed to maintain a blank expression. I’ve walked in on musicians doing the pre-gig pray/huddle thing. I’ve walked in on smokers, tokers, sniffers and snorters. I’ve even walked in on tribute bands and their tribute groupies. Oh yes I have. But until Neville, I’d never met one of my favourites in their underwear. Not all heroes wear capes, they say, but I can reveal that some of them wear large, functional and very clean Y-fronts.

Anyway, he signed the records – ‘That’s moi fave,’ he says of Gangsters, then, looking worriedly over my shoulder, asks to the empty corridor behind me, “Where’s all me fans?” As he sauntered off to find them – still in his Y-fronts – I went off to pack my treasured singles safely into the back of my car.

You’ll need to root around for this – Facebook is your best bet – but there’s an absolutely dynamite video performance of Gangsters on American TV that catches The Specials in April 1980, just as they are hitting their stride. Broadcast by Saturday Night Live (hence the block on YouTube and here on WordPress) it shows The Specials in all their jerky elbowed, suedeheaded and suited up youthful glory. From the opening shot of Neville standing on a staircase, barking the ‘Bernie Rhodes’ intro while brandishing a Tommy gun – can you imagine that on the telly nowadays?! – to his train-track-toasting on the microphone and the rest of the group in total syncopation, it’s just about my favourite archive live video. The energy coming from the screen as the band play it just a touch faster, just a touch more frantic than the 7″ release, could power Coventry for a year.

Standing either side of a hyper-animated Terry Hall, Neville and Lynval Golding provide the metaphorical yin and yang of the performance. One black, one white, Roddy on dark guitar, Lynval playing a light-coloured one, his arms making acute angles between elbow and bicep as he chops into the chords, Roddy’s legs forming obtuse angles as he slides them waaay out to rattle off the twanging punk-a-billy solo. To the side of them, Jerry surfs the organ, directing his band with already unnecessary nods and looks. All that practice, all those live shows as the Coventry Automatics has sharpened them up as neatly as the mohair suits they sport. Behind them, Horace manages to maintain both a solid bass line and tireless dance stance. Beside him, keeping it all together is John Bradbury, his clattering kit sounding exactly like a row of garbage cans that Benny and Choo-Choo have knocked over in the alley while escaping Officer Dibble. I tried to upload a version of it here, but it won’t go. Try Facebook if you can. You won’t be disappointed.

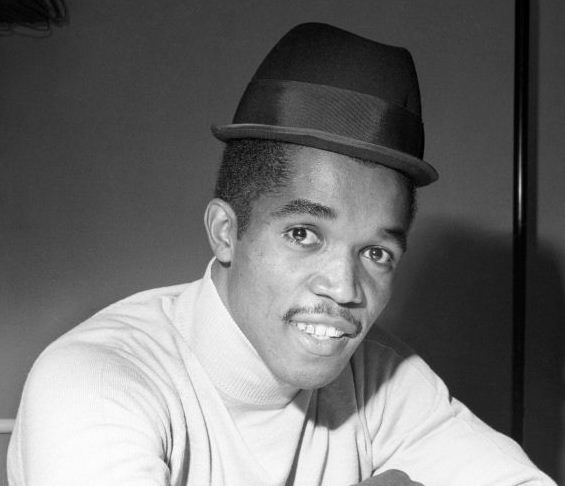

Reggae and ska has a long history of copying, borrowing, twisting and turning tunes, words and styles into brand new things. Gangsters, as you well know, was based on Prince Buster’s Al Capone. From the intro to the toasting, the repeating riff to the sheer excitement emanating from its heavy-set grooves, it’s a modern update on an old classic and something that 2-Tone acts would have a lot of success from. Not that I knew that as a 10-year old.

Prince Buster – Al Capone