It’s bombastic, booming and utterly brilliant. The Beethoven’s 5th of that awfully-named Britpop era.

It’s the drums.! Fucking great echoing and cavernous drums, like Hal Blaine on Hulk-sized steroids, forearms like Popeye as he nails the four to the floor. Tambourines ride the hi-hats, percussive and metallic, clattering toms tumble like the walls of Jericho. Biblical, as a bow-legged frontman of the times was wont to proclaim.

It’s the strings! The total antithesis of the era’s coke-flecked guitar bands’ syrupy and de-rigueur, bolted on after-thoughts, these are fucking great strings, soaring and sweeping and swooning their way through the summer of ‘95 with graceful elan, the way they might’ve done 30 years previously had The Beatles been commissioned to write a smash hit for Dusty Springfield;

Oh, the guitars! It’s the great guitars, the fucking great guitars, electrified and fried, feedbacking and freewheeling, searing and tearing and twanging and chugging their holy and wholly amplified way from uproarious beginning to spent out end. Six nickel-wound and steel strings never sounded so alive and so essential before now.

It’s the incidentals; the way the guitar slips through the gears, taking those gliding vocals with it, the pause mid-way through when the guitar player plays some hammer ons around open chords (just the way he did in his previous band) before the expectant and fantastic lift-off as the vocalist breaks free and tears off out into the great wide open, hand claps and drum beats and gospel soul backing doing their best to hold on to his coat tails. What a fucking arrangement!

Oh yeah. The vocals. It’s all about the vocals. Great octave-leaping things of joy that neither you nor I, regardless of how often we’ve opened our hopeless holes and sung along, will ever be able to get close too. They start down here, somewhere around the diaphragm, and end up waaaay out there, somewhere north of the moon, beyond God and all the greats who’ve gone before. Fucking stratospheric and then some.

What. A. Fucking. Record.

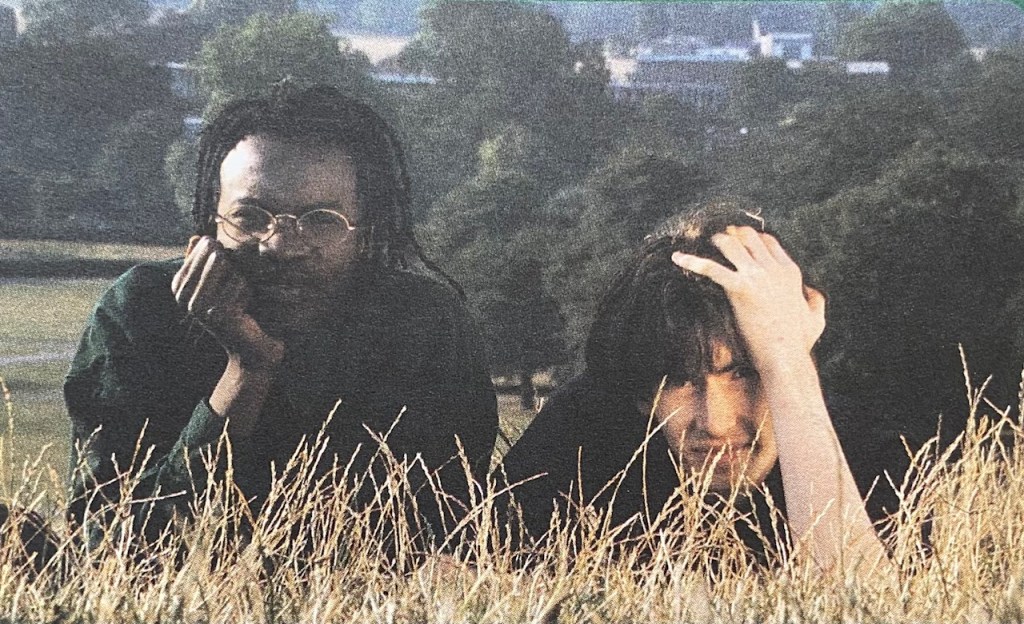

It’s Yes, by McAlmont & Butler, if you haven’t worked it out already.

I noticed that, from Bernard Butler’s Instagram feed, Yes had somehow turned 30 this weekend.

“I had a conviction from the moment of conception in the summer of 1994…make a piece of music that transcends…it had to make you feel the exhilaration of how sound and song can transform your experience of being a human.

It is totally ramshackle, noisy and out of tune (is it!?!) and that is how we all are flying through the universe…

I can visualise me and Mako (drums) in the cellar of Mike Hedges chateau, screaming at each other, David across the ballroom straining for every ridiculous key change without a concern.

We were all on fire and that’s what you hear.”

They could do it pretty spectacularly in the live setting too:

There’s a part in John Niven’s viciously brilliant Kill Your Friends when two A&R guys are shamelessly scouring the small print in the charts in Music Week to find the ideal hit-making producer required for one of their new signings.

“Mike Hedges…his mixes are just too middle-y. Not enough top or bottom end.”

Stelfox, the main protagonist, rolls his eyes in exasperation at the cluelessness of his A&R partner. It’s not informed knowledge that’s important in the A&R game, it’s having a view. Everyone must have a view, thinks Stelfox, even if your view is of no consequence at all.

Exhibit One: Mike Hedges manned the mixing desk when McAlmont & Butler recorded Yes, capturing forever the sound of pure magic via his fingertips and faders. (see above)

Exhibit Two: Mike Hedges would use his own blueprint within the year when helping the Manic Street Preachers construct A Design For Life, another of the decade’s stand-out tracks. (a future post for sure)

A record that’s both out of its time and forever timeless, Yes is an undeniable classic in anyone’s language.

Godlike genius here.

Me or the music?!

Tremendous song!!. Love the album it came off too.

The album was really just a compilation of the two singles and associated b-sides. Works well though.